- A-bomb Images

- The A-bomb Photographs of Shunkichi Kikuchi, Part Ⅰ: 783 Negatives Return to Hiroshima

The A-bomb Photographs of Shunkichi Kikuchi, Part Ⅰ: 783 Negatives Return to Hiroshima

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

(Originally published on January 17, 2007)

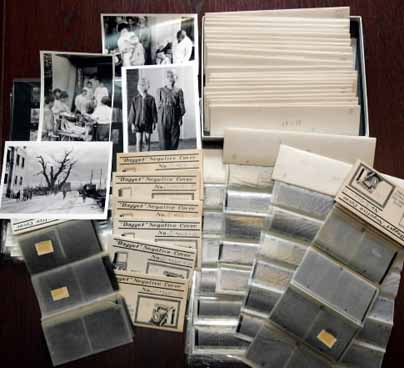

The negatives of photographs taken by Shunkichi Kikuchi (1916-1990), which vividly record the devastation of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, have been preserved in good condition. His wife, Mrs. Tokuko Kikuchi, 82, now living in Tokyo, has been in possession of 783 negatives, the largest number of A-bomb photos taken by one photographer. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum plans to examine them, stating that “They are valuable records for confirming and conveying the consequences of the atomic bombing.”

Between October 1 and 20, 1945, Mr. Kikuchi was in charge of taking still photos for a documentary film, as part of a production team for the “Special Committee for the Investigation of A-bomb Damage” set up by the former Japanese Ministry of Education.

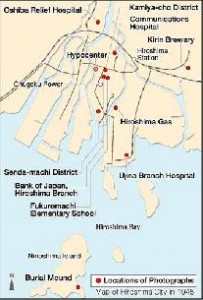

Seven-hundred of these negatives are in a 35 millimeter format and 83 negatives are 6x6 centimeters. The images depict patients, who were suffering from severe burns and radiation effects, receiving treatment at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and Hiroshima Communications Hospital. They also show dying parents and children at Oshiba Elementary School which was used as a relief hospital. The photographs are a vivid record of graphic scenes right after the atomic bombing.

In addition, documents recording the dates and locations of the photos have been kept, with notes describing some of the subjects in the images. Together with the negatives, these documents provide clues to the entire picture of the atomic bombing, as some aspects have not been clear before now.

Mrs. Kikuchi is eager to have the negatives examined in Hiroshima, saying, “My husband was devoted to preserving them so I usually keep them in a safe deposit box at the bank for protection. If Hiroshima is ready to make use of them, I’m happy to cooperate.”

The photographs taken by Mr. Kikuchi and Shigeo Hayashi (1918-2002), who also took still photos for the same documentary film, were seized by the U.S. military. Both photographers, however, were determined to preserve their negatives. Other negatives taken by photography team members of the Army Marine Headquarters stationed in Hiroshima had been discarded on orders of the Japanese Army before the arrival of the U.S. occupation forces, and those photos were scattered and lost.

The seized photographs were returned from the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in 1973. The number of images depicting Hiroshima reached 1200 and, among them, 214 were duplicates of photos taken by Mr. Kikuchi.

Though some of these photos had been shown in the media, they had become blurred due to repeated copying. The city of Hiroshima did not conduct a full-scale investigation of the photos, and under these circumstances, some mistaken or insufficient explanations were then attached. The negatives taken by Mr. Hayashi were donated to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 2000, and, after being researched thoroughly, these images are now available for viewing by the public in the museum’s “peace database.”

The Chugoku Shimbun took a close look at the world depicted in the negatives by reviewing the historical facts surrounding the photos taken by Mr. Kikuchi and comparing them with testimonies of A-bomb survivors.

“My husband was a quiet person, but he often reflected on his experience in Hiroshima, saying ‘I took those photos as a way to sustain my spirit.’ That’s why I put the negatives in the drawer where I keep my kimono and then in a safe deposit box in the bank.”

Mrs. Kikuchi, who married Mr. Kikuchi in 1947, showed me a number of cases in which the negatives were kept, after temporarily taking them from the bank to her home in Tokyo. She also showed me some documents that were labeled “Photography Division, Tohosha Company.”

According to the “Japan Photographers Dictionary,” Mr. Kikuchi was born in the city of Hanamaki in Iwate Prefecture. He graduated from a photography school in Tokyo and then joined the photography division of Tohosha Company, the overseas media outlet organized by the Department of the Army General Staff in 1941. This division had many first-rate photographers, including the division head Ihei Kimura.

On August 8, two days after Hiroshima was attacked, Dr. Yoshio Nishina flew to Hiroshima and identified “the special bomb as an atomic bomb.” With Dr. Nishina as its leader, the “Special Committee for the Investigation of A-bomb Damage” was set up by the Education Ministry on September 14.

The Japan Film Corporation conceived a plan to accompany the committee and produce a documentary film on the atomic bombing in conjunction with the investigation. The company asked the Tohosha Company to assign photographers to take still photographs.

At that time, even in Tokyo, people often heard fearful rumors of residual radiation. However, Mr. Kikuchi willingly took on the assignment. “I, too, stepped forward to go,” wrote Mr. Hayashi in his book entitled, “Entering the Hypocenter of Hiroshima.” I spoke with Mr. Hayashi before he died in 2002 and he told me, “I was young and I wasn’t aware of the horror of the atomic bomb.”

Mr. Kikuchi accompanied the medical team, one of five teams involved in making the documentary. Masao Yamanaka (1902-1978), the movie director in charge of the team, left notebooks entitled “Atomic Bombing Photography Journal” which recorded details of the filming. The journal was later donated to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum by his bereaved family.

Taking a close look at the records kept by the photographers and the director enables us to follow the trail of the team in Hiroshima at that time.

The team, including Mr. Kikuchi, left Tokyo Station on September 27. After 21 hours on the train, they reached Onomichi, where they took a motorboat to Ujina Port in Hiroshima on September 29. They settled at a dormitory in an iron factory in the eastern part of the city and began to take photos on October 1. Mr. Kikuchi roamed about the ruined city until October 20 and left Hiroshima on October 22.

However, the photographs taken by Mr. Kikuchi and Mr. Hayashi, who accompanied the physics team of the investigation, as well as reels of 35 millimeter film shot by the Japan Film Corporation, were seized by the U.S. military. Under the occupation, the “effectiveness of the atomic bomb” was considered classified information.

The 35 millimeter films were returned to Japan in 1967 and transferred into 16 millimeter, a format with less resolution than the original reels. At that time, the Ministry of Education restricted their screening to only “research or educational purposes.” As for the photographs, about 1200 images depicting the aftermath of the bombing, including 214 photos taken by Mr. Kikuchi, were returned in 1973. This news caused a considerable stir, though this development caught the photographers by surprise.

Mr. Kikuchi later commented on the release of these photographs in an article that appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun on July 29, 1973: “I was stunned to see my photos on TV with the explanation that they were likely taken by Japanese nationals,” he said. Blurry copies of the photos with erroneous descriptions were circulated.

During the occupation, Mr. Kikuchi and Mr. Hayashi made every effort to protect the negatives they had taken in Hiroshima. They urged that the collection be protected and made public, saying “the negatives will deteriorate and must be preserved.” But even the city of Hiroshima, which suffered the atomic bombing, did not seek to preserve the negatives at that time.

It was not until 2000, two years before his death in 2002, that Mr. Hayashi donated the negatives of the 232 photos he had taken to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Mr. Hayashi’s images can be seen on the “Peace Database” that the museum offers to the public. Meanwhile, the museum did not make an effort to locate Mr. Kikuchi’s negatives, too. Thus, Mrs. Kikuchi kept the negatives herself, preserving her husband’s legacy.

All the photographs used in this newspaper article were printed from these negatives. The dates of the photos were estimated based on the number of the negative and the documents left by Mr. Kikuchi. I was able to identify the locations and provide explanations of the subjects in the photos after extensive research and verification.

By the extraordinary efforts of the people who were willing to face the horror of the atomic bombing head-on, memories of “that day,” in the form of these photographs, remain vivid even after 62 years.

Hamako Honda appears in photographs taken at Hiroshima Communications Hospital

Hamako Honda, 79, studied a photo in which she appeared and recalled the scene: “I still remember that patient. Her eyeball was gone.” The photo was taken on the first floor of Hiroshima Communications Hospital, 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, where Ms. Honda was nursing the injured.

In 1955, the former Chugoku Telecommunications Bureau published a book entitled “Hiroshima Atomic Bombing Record.” In the section referring to Hiroshima Communications Hospital, the name “Nurse Wakita” appears after “Ophthalmologist Ayao Koyama.” That nurse was Ms. Honda, who was just 17 at the time. After leaving her hometown of Nakajima, in Ehime Prefecture, she began working at the Communications Hospital in Hiroshima.

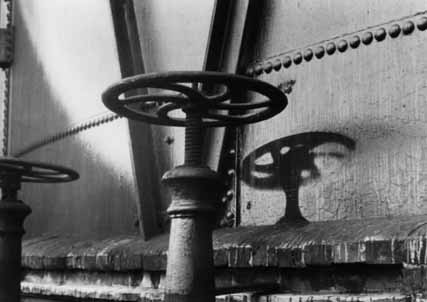

“I heard a great roaring sound,” said Ms. Honda. “But I was in the hallway and I wasn’t injured.” Dr. Koyama, though, who was head of the Ophthalmology Department, was peppered with glass fragments. At the time, in anticipation of possible air raids, there were no patients remaining in the hospital. However, men burned in the blast and running from nearby military facilities flooded the hospital. As Ms. Honda was dabbing oil on the victims’ burns, a furious fire broke out on the second floor of the building. After leading the soldiers to safety and then swimming across the Kyobashi River, she found herself fleeing all alone.

Ms. Honda returned to the hospital, which was charred but still standing, and spent many days and nights applying mercurochrome to the wounds of men and women, young and old. This treatment, though, could offer only small solace. “Human beings are such pitiful creatures,” she murmured.

In the hospital, everyone was indifferent to the dead bodies lying in the hallways and bathrooms. When patients with bloody diarrhea began to arrive, a symptom of acute radiation sickness, they were thought to be suffering from some kind of contagious dysentery and so they were isolated in a makeshift shelter outside. These patients, though, were unable to bear the heat in the shelter from the scorching sun and they desperately tried to enter the building, crawling on all fours. Other patients blocked their entry and as they fought, many died.

Dr. Koyama, who passed away at the age of 80 in 1991, took charge of the hospital when the director was badly injured. He left notes about his experience in the “Atomic Bomb Feature Edition of the Hiroshima City Medical Association Newsletter” issued in 1981. “It is terribly sad when we lose our humanity in circumstances where we are overwhelmed by misery.”

After hearing the Emperor’s address on the radio, marking the end of the war, Ms. Honda returned to her hometown where her own health deteriorated. She suffered from nosebleeds and painful gums. Though people around her whispered that she might soon die, she defied these predictions and came back to the hospital in Hiroshima. She slept at night in the darkroom of the Ophthalmology Department with blankets from an army engineering unit. She cooked rationed rice in an iron helmet as a substitute for a pan.

Photos of Ms. Honda were taken at this time. Director Masao Yamanaka, who was in charge of the medical team for the documentary film on the atomic bombing, left notes which recorded the continuing chaos in his “Atomic Bomb Journal.” Dr. Michihiko Hachiya, director of the hospital, expressed his frustration and anger in “Hiroshima Diary,” a book he published prior to his death in 1980 at the age of 76. “The patients had no home to return to and had no nutritious food,” he wrote. “The hospital was like a slum.”

Ms. Honda quit her job in July 1946. “Not because of my health,” she explained. “I didn’t feel comfortable with the new nurses who came from outside of Hiroshima.” Her extraordinary experiences of the atomic bombing made her feel distant from them.

After returning to her hometown, she married a relative who had been demobilized from the military. The couple, who raised a son and three daughters, maintained a grove of mandarin orange trees. In the summer, Ms. Honda often felt fatigue as she worked and wondered why. Although her husband suffered a stroke and died in 1996 at the age of 79, she continued to work at the orange grove. She now lives with her son and daughter-in-law.

“I never talk about the bombing around here, as it might create some discrimination against us,” she said, referring to her children and grandchildren. “My husband told me about fighting overseas as a soldier for eight years and eating snakes and mice. I detest war. I want to shout this out to the world.”

Related articles

The A-bomb Photographs of Shunkichi Kikuchi, Part Ⅱ: Images from Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital

The A-bomb Photographs of Shunkichi Kikuchi, Part Ⅲ: Tremendous Pain

Panoramic photos found of Hiroshima's reconstruction (Jan. 18, 2008)

(Originally published on January 17, 2007)

The negatives of photographs taken by Shunkichi Kikuchi (1916-1990), which vividly record the devastation of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, have been preserved in good condition. His wife, Mrs. Tokuko Kikuchi, 82, now living in Tokyo, has been in possession of 783 negatives, the largest number of A-bomb photos taken by one photographer. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum plans to examine them, stating that “They are valuable records for confirming and conveying the consequences of the atomic bombing.”

Between October 1 and 20, 1945, Mr. Kikuchi was in charge of taking still photos for a documentary film, as part of a production team for the “Special Committee for the Investigation of A-bomb Damage” set up by the former Japanese Ministry of Education.

Seven-hundred of these negatives are in a 35 millimeter format and 83 negatives are 6x6 centimeters. The images depict patients, who were suffering from severe burns and radiation effects, receiving treatment at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and Hiroshima Communications Hospital. They also show dying parents and children at Oshiba Elementary School which was used as a relief hospital. The photographs are a vivid record of graphic scenes right after the atomic bombing.

In addition, documents recording the dates and locations of the photos have been kept, with notes describing some of the subjects in the images. Together with the negatives, these documents provide clues to the entire picture of the atomic bombing, as some aspects have not been clear before now.

Mrs. Kikuchi is eager to have the negatives examined in Hiroshima, saying, “My husband was devoted to preserving them so I usually keep them in a safe deposit box at the bank for protection. If Hiroshima is ready to make use of them, I’m happy to cooperate.”

The photographs taken by Mr. Kikuchi and Shigeo Hayashi (1918-2002), who also took still photos for the same documentary film, were seized by the U.S. military. Both photographers, however, were determined to preserve their negatives. Other negatives taken by photography team members of the Army Marine Headquarters stationed in Hiroshima had been discarded on orders of the Japanese Army before the arrival of the U.S. occupation forces, and those photos were scattered and lost.

The seized photographs were returned from the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in 1973. The number of images depicting Hiroshima reached 1200 and, among them, 214 were duplicates of photos taken by Mr. Kikuchi.

Though some of these photos had been shown in the media, they had become blurred due to repeated copying. The city of Hiroshima did not conduct a full-scale investigation of the photos, and under these circumstances, some mistaken or insufficient explanations were then attached. The negatives taken by Mr. Hayashi were donated to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 2000, and, after being researched thoroughly, these images are now available for viewing by the public in the museum’s “peace database.”

The Chugoku Shimbun took a close look at the world depicted in the negatives by reviewing the historical facts surrounding the photos taken by Mr. Kikuchi and comparing them with testimonies of A-bomb survivors.

“My husband was a quiet person, but he often reflected on his experience in Hiroshima, saying ‘I took those photos as a way to sustain my spirit.’ That’s why I put the negatives in the drawer where I keep my kimono and then in a safe deposit box in the bank.”

Mrs. Kikuchi, who married Mr. Kikuchi in 1947, showed me a number of cases in which the negatives were kept, after temporarily taking them from the bank to her home in Tokyo. She also showed me some documents that were labeled “Photography Division, Tohosha Company.”

According to the “Japan Photographers Dictionary,” Mr. Kikuchi was born in the city of Hanamaki in Iwate Prefecture. He graduated from a photography school in Tokyo and then joined the photography division of Tohosha Company, the overseas media outlet organized by the Department of the Army General Staff in 1941. This division had many first-rate photographers, including the division head Ihei Kimura.

On August 8, two days after Hiroshima was attacked, Dr. Yoshio Nishina flew to Hiroshima and identified “the special bomb as an atomic bomb.” With Dr. Nishina as its leader, the “Special Committee for the Investigation of A-bomb Damage” was set up by the Education Ministry on September 14.

The Japan Film Corporation conceived a plan to accompany the committee and produce a documentary film on the atomic bombing in conjunction with the investigation. The company asked the Tohosha Company to assign photographers to take still photographs.

At that time, even in Tokyo, people often heard fearful rumors of residual radiation. However, Mr. Kikuchi willingly took on the assignment. “I, too, stepped forward to go,” wrote Mr. Hayashi in his book entitled, “Entering the Hypocenter of Hiroshima.” I spoke with Mr. Hayashi before he died in 2002 and he told me, “I was young and I wasn’t aware of the horror of the atomic bomb.”

Mr. Kikuchi accompanied the medical team, one of five teams involved in making the documentary. Masao Yamanaka (1902-1978), the movie director in charge of the team, left notebooks entitled “Atomic Bombing Photography Journal” which recorded details of the filming. The journal was later donated to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum by his bereaved family.

Taking a close look at the records kept by the photographers and the director enables us to follow the trail of the team in Hiroshima at that time.

The team, including Mr. Kikuchi, left Tokyo Station on September 27. After 21 hours on the train, they reached Onomichi, where they took a motorboat to Ujina Port in Hiroshima on September 29. They settled at a dormitory in an iron factory in the eastern part of the city and began to take photos on October 1. Mr. Kikuchi roamed about the ruined city until October 20 and left Hiroshima on October 22.

However, the photographs taken by Mr. Kikuchi and Mr. Hayashi, who accompanied the physics team of the investigation, as well as reels of 35 millimeter film shot by the Japan Film Corporation, were seized by the U.S. military. Under the occupation, the “effectiveness of the atomic bomb” was considered classified information.

The 35 millimeter films were returned to Japan in 1967 and transferred into 16 millimeter, a format with less resolution than the original reels. At that time, the Ministry of Education restricted their screening to only “research or educational purposes.” As for the photographs, about 1200 images depicting the aftermath of the bombing, including 214 photos taken by Mr. Kikuchi, were returned in 1973. This news caused a considerable stir, though this development caught the photographers by surprise.

Mr. Kikuchi later commented on the release of these photographs in an article that appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun on July 29, 1973: “I was stunned to see my photos on TV with the explanation that they were likely taken by Japanese nationals,” he said. Blurry copies of the photos with erroneous descriptions were circulated.

During the occupation, Mr. Kikuchi and Mr. Hayashi made every effort to protect the negatives they had taken in Hiroshima. They urged that the collection be protected and made public, saying “the negatives will deteriorate and must be preserved.” But even the city of Hiroshima, which suffered the atomic bombing, did not seek to preserve the negatives at that time.

It was not until 2000, two years before his death in 2002, that Mr. Hayashi donated the negatives of the 232 photos he had taken to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Mr. Hayashi’s images can be seen on the “Peace Database” that the museum offers to the public. Meanwhile, the museum did not make an effort to locate Mr. Kikuchi’s negatives, too. Thus, Mrs. Kikuchi kept the negatives herself, preserving her husband’s legacy.

All the photographs used in this newspaper article were printed from these negatives. The dates of the photos were estimated based on the number of the negative and the documents left by Mr. Kikuchi. I was able to identify the locations and provide explanations of the subjects in the photos after extensive research and verification.

By the extraordinary efforts of the people who were willing to face the horror of the atomic bombing head-on, memories of “that day,” in the form of these photographs, remain vivid even after 62 years.

Hamako Honda appears in photographs taken at Hiroshima Communications Hospital

Hamako Honda, 79, studied a photo in which she appeared and recalled the scene: “I still remember that patient. Her eyeball was gone.” The photo was taken on the first floor of Hiroshima Communications Hospital, 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, where Ms. Honda was nursing the injured.

In 1955, the former Chugoku Telecommunications Bureau published a book entitled “Hiroshima Atomic Bombing Record.” In the section referring to Hiroshima Communications Hospital, the name “Nurse Wakita” appears after “Ophthalmologist Ayao Koyama.” That nurse was Ms. Honda, who was just 17 at the time. After leaving her hometown of Nakajima, in Ehime Prefecture, she began working at the Communications Hospital in Hiroshima.

“I heard a great roaring sound,” said Ms. Honda. “But I was in the hallway and I wasn’t injured.” Dr. Koyama, though, who was head of the Ophthalmology Department, was peppered with glass fragments. At the time, in anticipation of possible air raids, there were no patients remaining in the hospital. However, men burned in the blast and running from nearby military facilities flooded the hospital. As Ms. Honda was dabbing oil on the victims’ burns, a furious fire broke out on the second floor of the building. After leading the soldiers to safety and then swimming across the Kyobashi River, she found herself fleeing all alone.

Ms. Honda returned to the hospital, which was charred but still standing, and spent many days and nights applying mercurochrome to the wounds of men and women, young and old. This treatment, though, could offer only small solace. “Human beings are such pitiful creatures,” she murmured.

In the hospital, everyone was indifferent to the dead bodies lying in the hallways and bathrooms. When patients with bloody diarrhea began to arrive, a symptom of acute radiation sickness, they were thought to be suffering from some kind of contagious dysentery and so they were isolated in a makeshift shelter outside. These patients, though, were unable to bear the heat in the shelter from the scorching sun and they desperately tried to enter the building, crawling on all fours. Other patients blocked their entry and as they fought, many died.

Dr. Koyama, who passed away at the age of 80 in 1991, took charge of the hospital when the director was badly injured. He left notes about his experience in the “Atomic Bomb Feature Edition of the Hiroshima City Medical Association Newsletter” issued in 1981. “It is terribly sad when we lose our humanity in circumstances where we are overwhelmed by misery.”

After hearing the Emperor’s address on the radio, marking the end of the war, Ms. Honda returned to her hometown where her own health deteriorated. She suffered from nosebleeds and painful gums. Though people around her whispered that she might soon die, she defied these predictions and came back to the hospital in Hiroshima. She slept at night in the darkroom of the Ophthalmology Department with blankets from an army engineering unit. She cooked rationed rice in an iron helmet as a substitute for a pan.

Photos of Ms. Honda were taken at this time. Director Masao Yamanaka, who was in charge of the medical team for the documentary film on the atomic bombing, left notes which recorded the continuing chaos in his “Atomic Bomb Journal.” Dr. Michihiko Hachiya, director of the hospital, expressed his frustration and anger in “Hiroshima Diary,” a book he published prior to his death in 1980 at the age of 76. “The patients had no home to return to and had no nutritious food,” he wrote. “The hospital was like a slum.”

Ms. Honda quit her job in July 1946. “Not because of my health,” she explained. “I didn’t feel comfortable with the new nurses who came from outside of Hiroshima.” Her extraordinary experiences of the atomic bombing made her feel distant from them.

After returning to her hometown, she married a relative who had been demobilized from the military. The couple, who raised a son and three daughters, maintained a grove of mandarin orange trees. In the summer, Ms. Honda often felt fatigue as she worked and wondered why. Although her husband suffered a stroke and died in 1996 at the age of 79, she continued to work at the orange grove. She now lives with her son and daughter-in-law.

“I never talk about the bombing around here, as it might create some discrimination against us,” she said, referring to her children and grandchildren. “My husband told me about fighting overseas as a soldier for eight years and eating snakes and mice. I detest war. I want to shout this out to the world.”

Related articles

The A-bomb Photographs of Shunkichi Kikuchi, Part Ⅱ: Images from Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital

The A-bomb Photographs of Shunkichi Kikuchi, Part Ⅲ: Tremendous Pain

Panoramic photos found of Hiroshima's reconstruction (Jan. 18, 2008)