- A-bomb Images

- Record of Hiroshima: Nuclear Age Recorded

Record of Hiroshima: Nuclear Age Recorded

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

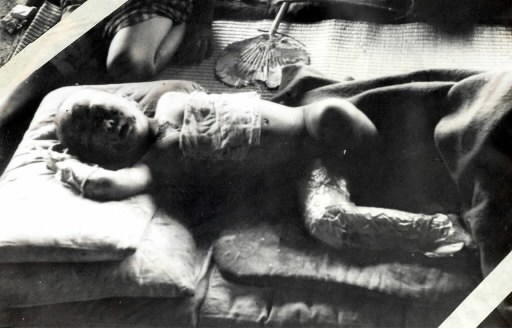

People shudder when they see these images of the atomic bombing. The photos, from The Collection of Photographs of the War Damage in Hiroshima, were taken at relief stations which took in residents of Hiroshima in the aftermath of the A-bomb blast. Tomorrow will mark the 60th anniversary of the bombing. Some of the images that accompany this article may be appalling, but they show the harsh reality of what happened that day to human beings on the ground. Out of respect to the dignity of the victims, and the lingering sorrow of the bereaved families, photos considered too cruel have not been included. Still, the images here explicitly show the atrocity and inhumanity of the atomic bombing. What really happened on August 6, 1945? Do those consequences still impact the present? And what must we do for the future? These photos force us all to reflect seriously on such questions.

Keisuke Misonoo, who died in 1995 at the age of 82, had held in his possession 52 photos taken by the photography team of the Army Marine Headquarters. He was a forefather of radiation medicine in Japan and a professor at the Army Medical College. As a member of the second survey team dispatched by the Ministry of War, he entered Hiroshima on August 14 and investigated the A-bomb damage by studying various aspects of the destruction, including the teeth of victims. The war ended the next day, but Mr. Misonoo remained in Hiroshima and pursued this investigation of the damage until November 21. The findings were given to U.S. forces in Japan, but were later published in 1953 in Collection of Reports on the A-bomb Damage, issue by Gakujutsu Kenkyu Kaigi, a council for academic research.

Mr. Misonoo’s wife, Tomoko, 85, is now a resident of Toshima Ward, Tokyo. Recalling that time, she said, “I helped with the English translations. I never actually saw the photos, though, so I don’t think my husband ever brought them home.” She attests that the notations on each image, specifying the patients’ symptoms and the names of the relief stations, were not written by her husband.

Collection of Photographs of the War Damage in Hiroshima, stamped “Confidential” and “Marine Army Medical Department,” was donated by Mr. Misonoo to the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council in 1973. The mayor of Hiroshima was the president of the council. The following year, Mr. Misoono became the chairman of the Council on Medical Care for the Atomic Bomb Exposed. He was eligible to receive the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate because he entered Hiroshima before August 20, but he refused to apply, saying, “I went to Hiroshima to help with the war effort. I don’t deserve it.” Was his reluctance out of consideration for the scores of victims?

These 52 photos convey the tremendous destruction wrought by the atomic bomb, which exploded above the city. They show the First National School (now Danbara Junior High School, located in Minami Ward), which was used as a relief station immediately after the bombing; Oko National School (now Oko Elementary School); the Marine Training Division (located at today’s Mazda Ujina West Plant), where a field hospital was erected... One after another, the images reveal dreadful scenes.

Half of the photos appeared in The First Atomic Bombing: A Photographic Record of Hiroshima, published on August 14, 1952 by a Tokyo-based publisher, Asahi Press, soon after the occupation ended and Japan regained its sovereignty. The book, however, does not explain who took the photos or where they were taken. One of the images was printed in Life, an American magazine, on September 29, 1952, along with other photos to show, uncensored, the horrifying effects of the bombing for the first time in the United States.

In an article published the following year, a resident of Hiroshima said that he had taken more than 100 photos and offered them to Life magazine and other publishers. When I searched for him, I learned that he had passed away eight years ago. His wife said that when he was still living, he gave the photos and their negatives to someone else, who has also since died. I could glean no further details, nor did I know whether any other photos taken in the aftermath of the atomic bombing existed.

Apart from the 52 photos mentioned, the number of photos now existing, taken between August 6 and 15, the day the war ended, totals 259. They were taken by 12 people: nine survivors of the Hiroshima bombing and three newspaper reporters from Osaka, dispatched by the Asahi and the Mainichi newspapers and Domei (today’s Kyodo News). By the end of 1945, 2,702 photos were apparently taken by 37 Japanese nationals, including a photographer who traveled from Tokyo to Hiroshima in late September with Gakujutsu Kenkyu Kaigi.

These are the figures obtained by Michio Ide, 64, a photographer and a member of the research group studying the materials held at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Searching for photos from those days, he made careful counts of the images. “No more photos of the atomic bombings will be taken. We must clarify the information involving the existing photos and preserve them for future use,” said Mr. Ide, who will continue his patient study of the A-bomb images.

Because these photos offer important information to help illuminate the larger picture of the atomic bombing, which in many ways is still unknown since so much was destroyed, they are valuable records that must be conveyed to future generations. We live in the nuclear age, which was born in Hiroshima. It is therefore our duty to clarify the facts found in these records for the world to remember and pursue the cause of peace.

The magnitude of the atomic bombing

The atomic bomb, detonated with uranium 235, generated a tremendous blast. Near the hypocenter, the pressure was roughly 30 tons per square meter; heat rays raised temperatures on the ground to about 3,000 degrees Celsius; and the bomb also emitted a large amount of neutron and gamma rays.

Even when people managed to survive these effects, they soon exhibited such symptoms as vomiting, high fever, and diarrhea. About two weeks later, they began losing their hair. The radiation damage induced various cancers in the survivors, with leukemia appearing first, followed by gastric, thyroid, and breast cancers. Though 60 years have passed, A-bomb survivors continue to show a high incidence of developing different forms of cancer.

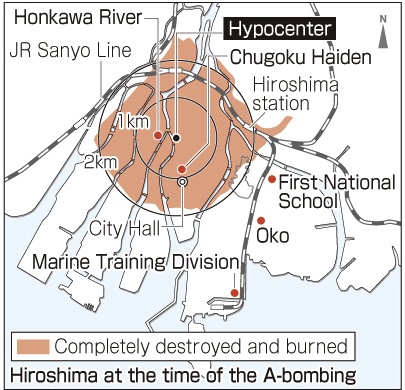

According to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a publication compiled by the two cities in 1979, roughly 350,000 people were directly exposed to the atomic bomb in Hiroshima; about 77,600 people were exposed to residual radiation when they entered the city; and about 11,300 people who were engaged in rescue efforts and other activities were also exposed to radiation. It is believed that 90 percent of those who were within one kilometer of the hypocenter and 80 percent of those within two kilometers of the hypocenter died by the end of 1945.

Photographs of Hiroshima in ruins, taken from the rooftop of the five-story head office of Chugoku Haiden, in four directions. Chugoku Haiden was an electric power company located in today’s Naka Ward, 680 meters from the hypocenter. (Photographs by Yoshita Kishimoto)

Yoshita Kishimoto, who died in 1989 at the age of 87, opened a photo studio in Hiroshima in 1940. His eldest daughter, who was 8 years old and a student at Seibi National School, died in the atomic bombing. (The school does not exist today.) He had no desire to take photos of the destruction, but at the request of Chugoku Haiden (now the Chugoku Electric Power Company), he began taking photos of the electric power facilities in the city in November 1945. His eldest son, Tan, who is 70 years old, took over the photo studio in Higashi Hakushima-cho in downtown Hiroshima and has preserved the negatives.

Building damage

The area within two kilometers of the hypocenter was completely burned by the atomic bombing. This is clearly shown in the aerial photograph taken by U. S. forces on August 11, five days after the blast. According to the survey conducted by the City of Hiroshima on August 10, 1946, nearly 100 percent of the 19,667 buildings within one kilometer of the hypocenter were completely burned and destroyed; 99 percent of 25,526 buildings between one kilometer and two kilometers from the hypocenter were either completely burned and destroyed or seriously damaged. Of a total of 76,327 buildings in the city, 92 percent were damaged, including those half-destroyed, half-burned, or seriously damaged.

(Originally published on August 5, 2005)

A-bomb torched the bodies and futures of people in the city

People shudder when they see these images of the atomic bombing. The photos, from The Collection of Photographs of the War Damage in Hiroshima, were taken at relief stations which took in residents of Hiroshima in the aftermath of the A-bomb blast. Tomorrow will mark the 60th anniversary of the bombing. Some of the images that accompany this article may be appalling, but they show the harsh reality of what happened that day to human beings on the ground. Out of respect to the dignity of the victims, and the lingering sorrow of the bereaved families, photos considered too cruel have not been included. Still, the images here explicitly show the atrocity and inhumanity of the atomic bombing. What really happened on August 6, 1945? Do those consequences still impact the present? And what must we do for the future? These photos force us all to reflect seriously on such questions.

Keisuke Misonoo, who died in 1995 at the age of 82, had held in his possession 52 photos taken by the photography team of the Army Marine Headquarters. He was a forefather of radiation medicine in Japan and a professor at the Army Medical College. As a member of the second survey team dispatched by the Ministry of War, he entered Hiroshima on August 14 and investigated the A-bomb damage by studying various aspects of the destruction, including the teeth of victims. The war ended the next day, but Mr. Misonoo remained in Hiroshima and pursued this investigation of the damage until November 21. The findings were given to U.S. forces in Japan, but were later published in 1953 in Collection of Reports on the A-bomb Damage, issue by Gakujutsu Kenkyu Kaigi, a council for academic research.

Mr. Misonoo’s wife, Tomoko, 85, is now a resident of Toshima Ward, Tokyo. Recalling that time, she said, “I helped with the English translations. I never actually saw the photos, though, so I don’t think my husband ever brought them home.” She attests that the notations on each image, specifying the patients’ symptoms and the names of the relief stations, were not written by her husband.

Collection of Photographs of the War Damage in Hiroshima, stamped “Confidential” and “Marine Army Medical Department,” was donated by Mr. Misonoo to the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council in 1973. The mayor of Hiroshima was the president of the council. The following year, Mr. Misoono became the chairman of the Council on Medical Care for the Atomic Bomb Exposed. He was eligible to receive the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate because he entered Hiroshima before August 20, but he refused to apply, saying, “I went to Hiroshima to help with the war effort. I don’t deserve it.” Was his reluctance out of consideration for the scores of victims?

These 52 photos convey the tremendous destruction wrought by the atomic bomb, which exploded above the city. They show the First National School (now Danbara Junior High School, located in Minami Ward), which was used as a relief station immediately after the bombing; Oko National School (now Oko Elementary School); the Marine Training Division (located at today’s Mazda Ujina West Plant), where a field hospital was erected... One after another, the images reveal dreadful scenes.

Half of the photos appeared in The First Atomic Bombing: A Photographic Record of Hiroshima, published on August 14, 1952 by a Tokyo-based publisher, Asahi Press, soon after the occupation ended and Japan regained its sovereignty. The book, however, does not explain who took the photos or where they were taken. One of the images was printed in Life, an American magazine, on September 29, 1952, along with other photos to show, uncensored, the horrifying effects of the bombing for the first time in the United States.

In an article published the following year, a resident of Hiroshima said that he had taken more than 100 photos and offered them to Life magazine and other publishers. When I searched for him, I learned that he had passed away eight years ago. His wife said that when he was still living, he gave the photos and their negatives to someone else, who has also since died. I could glean no further details, nor did I know whether any other photos taken in the aftermath of the atomic bombing existed.

Apart from the 52 photos mentioned, the number of photos now existing, taken between August 6 and 15, the day the war ended, totals 259. They were taken by 12 people: nine survivors of the Hiroshima bombing and three newspaper reporters from Osaka, dispatched by the Asahi and the Mainichi newspapers and Domei (today’s Kyodo News). By the end of 1945, 2,702 photos were apparently taken by 37 Japanese nationals, including a photographer who traveled from Tokyo to Hiroshima in late September with Gakujutsu Kenkyu Kaigi.

These are the figures obtained by Michio Ide, 64, a photographer and a member of the research group studying the materials held at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Searching for photos from those days, he made careful counts of the images. “No more photos of the atomic bombings will be taken. We must clarify the information involving the existing photos and preserve them for future use,” said Mr. Ide, who will continue his patient study of the A-bomb images.

Because these photos offer important information to help illuminate the larger picture of the atomic bombing, which in many ways is still unknown since so much was destroyed, they are valuable records that must be conveyed to future generations. We live in the nuclear age, which was born in Hiroshima. It is therefore our duty to clarify the facts found in these records for the world to remember and pursue the cause of peace.

The magnitude of the atomic bombing

The atomic bomb, detonated with uranium 235, generated a tremendous blast. Near the hypocenter, the pressure was roughly 30 tons per square meter; heat rays raised temperatures on the ground to about 3,000 degrees Celsius; and the bomb also emitted a large amount of neutron and gamma rays.

Even when people managed to survive these effects, they soon exhibited such symptoms as vomiting, high fever, and diarrhea. About two weeks later, they began losing their hair. The radiation damage induced various cancers in the survivors, with leukemia appearing first, followed by gastric, thyroid, and breast cancers. Though 60 years have passed, A-bomb survivors continue to show a high incidence of developing different forms of cancer.

According to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a publication compiled by the two cities in 1979, roughly 350,000 people were directly exposed to the atomic bomb in Hiroshima; about 77,600 people were exposed to residual radiation when they entered the city; and about 11,300 people who were engaged in rescue efforts and other activities were also exposed to radiation. It is believed that 90 percent of those who were within one kilometer of the hypocenter and 80 percent of those within two kilometers of the hypocenter died by the end of 1945.

Photographs of Hiroshima in ruins, taken from the rooftop of the five-story head office of Chugoku Haiden, in four directions. Chugoku Haiden was an electric power company located in today’s Naka Ward, 680 meters from the hypocenter. (Photographs by Yoshita Kishimoto)

Yoshita Kishimoto, who died in 1989 at the age of 87, opened a photo studio in Hiroshima in 1940. His eldest daughter, who was 8 years old and a student at Seibi National School, died in the atomic bombing. (The school does not exist today.) He had no desire to take photos of the destruction, but at the request of Chugoku Haiden (now the Chugoku Electric Power Company), he began taking photos of the electric power facilities in the city in November 1945. His eldest son, Tan, who is 70 years old, took over the photo studio in Higashi Hakushima-cho in downtown Hiroshima and has preserved the negatives.

Building damage

The area within two kilometers of the hypocenter was completely burned by the atomic bombing. This is clearly shown in the aerial photograph taken by U. S. forces on August 11, five days after the blast. According to the survey conducted by the City of Hiroshima on August 10, 1946, nearly 100 percent of the 19,667 buildings within one kilometer of the hypocenter were completely burned and destroyed; 99 percent of 25,526 buildings between one kilometer and two kilometers from the hypocenter were either completely burned and destroyed or seriously damaged. Of a total of 76,327 buildings in the city, 92 percent were damaged, including those half-destroyed, half-burned, or seriously damaged.

(Originally published on August 5, 2005)