Peace Seeds: Teens in Hiroshima Sow Seeds of Peace (Part 28)

Feb. 25, 2016

Fleeing from conflict in their homelands, refugees face further difficulties in Japan

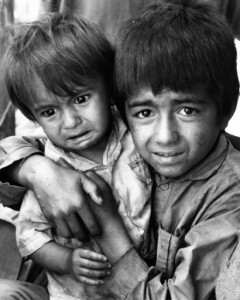

In other parts of the world, there are people who have fled for their lives from the destruction and chaos of their war-torn homelands. In recent days, the flight of many refugees from Syria and other volatile countries to nations of the European Union (EU) has drawn worldwide attention. Because their home countries are politically unstable and unsafe, they feel no other option but to forge new lives elsewhere.

Some refugees have come as far as Japan. The number of people from other nations who have sought residency here as a “refugee” was 7,586 (preliminary figure) in 2015, which marked a record-high for the fifth consecutive year. On the other hand, the Japanese government officially recognized only 27 as refugees last year, which was 16 more than the year before. Japan is clearly not very open to taking in refugees.

Hiroshima Prefecture is now home to some refugees, too, who fled from civil war in their countries. The junior writers met with two, from Afghanistan and Cambodia, and listened to their terrible experiences of war and suffering. And we pondered what we might do, as human beings, to help others in such circumstances.

Kohi Ahmad Khlid, 35, from Afghanistan: “We’re all the same human beings.”

“Weapons have destroyed my country and my family’s lives. I want all weapons gone from this world,” said Kohi Ahmad Khlid, sharing his strong wish. Mr. Khlid, 35, is from Afghanistan and he now lives in Higashihiroshima and works for a trading company. Because of the fighting there, he barely escaped with his life, arriving in Japan 18 years ago. He understands, first-hand, how important and fragile peace really is.

When Mr. Khlid was 10, the civil war among the Mujahedeen (Islamic soldiers) grew more intense. In 1997, at the age of 16, he moved from Mazar-e-Sharif, his hometown, to Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, because the Taliban, a militant Islamic group, had approached the town.

In Kabul, he encountered a city without functional public utilities or radio and television programs, which were banned. Several months later, Mr. Khlid headed to Peshawar, a city in northern Pakistan, which neighbors Afghanistan. The city was in chaos, with local police arresting people without cause to extort money, and Taliban soldiers hiding out there. “At that point, I made up my mind to get much farther away,” he said.

In 1998, Mr. Khlid, with the help of an agent, traveled alone through Thailand to Tokyo to visit a relative in Japan, and sought help in this country.

However, at times he felt that the Japanese people around him couldn’t really understand his plight, as in the cold-hearted responses he experienced from the staff at the Immigration Bureau. He once called his mother abroad and cried, telling her, “We’re all the same human beings. Why do I have to be treated like this?”

Meanwhile, he received a job offer from a volunteer at his Japanese language class and began to take steps forward toward independence. He worked very hard as he moved to various locations and took on various kinds of work. In 2002, he became a permanent resident in Japan, then married an Afghan woman in 2008 and moved to Higashihiroshima. They now have two children.

Because his work prevented him from continuing his education or pursuing other interests, he feels strongly about gaining more education for the future. He hopes that Japan will develop an assistance program for refugees, as in other countries.

Mr. Khlid has now been living in Japan longer than the period of time he spent in Afghanistan. “I don’t have any intention of going back to my home country, which has been warped so badly by more powerful nations, and is unable to realize peace,” he said. “If people who are armed seize power, others could be killed, over simply what they say, and this could spark more war. We don’t know when our happy lives in Japan, including my own, might be lost, like in Afghanistan. So we have to create a world that’s free of weapons.” (Written by Shino Taniguchi, 17, Reiko Takaya, 17, and Nako Yoshimoto, 16)

Profile

Kohi Ahmad Khlid

Fled to Pakistan with his family in 1997 because of the Afghan civil war. In 1998, he came alone to Japan via Thailand. He has been living in Higashihiroshima since 2012.

Keywords

Afghan civil war

Insurgent groups, which received aid from the United States and other nations, fought against the military deployments made by the former Soviet Union in 1979. Even after the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan, the Mujahedeen (Islamic soldiers) fought one other to take control, and the entire country fell into disorder. In 1996, the Taliban, an Islamic militant group, seized control of the capital, Kabul, and installed its regime. Then, Al-Qaida, an international terrorist group that the Taliban had protected, staged terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, and the United States launched military operations in Afghanistan. Though the Taliban regime has collapsed, U.S. forces are still stationed there.

Yuko Haritomi, 48, from Cambodia: “The person right in front of me was killed by a bomb.”

APSARAS, a Cambodian and Vietnamese restaurant in Higashihiroshima, marked its 20th anniversary in January of this year. Yuko Haritomi (or Eap Yeuyeun, her Cambodian name), 48, the owner of the restaurant, arrived in Japan 29 years ago after fleeing from Cambodia’s civil war. “The smiles of my customers have given me emotional support for my life in Japan,” she said.

In 1975, when Ms. Haritomi lived in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, her life was turned upside down after Pol Pot and his supporters rose to power. At first, she was told to stay at a farming village for just three days, but eventually she was forced into living there. Although she was an elementary school student at the time, she was separated from her parents and made to do farm work from early morning to after sunset until the regime collapsed in 1979. She was given only two meals a day, and if she stole food or slacked off in her work, she would have been killed. “I was terrified every day,” she said.

When she was finally freed from forced labor, she was unable to walk without a cane because of malnutrition and overwork. While running away from falling bombs, the person in front of her was struck and blown into pieces of flesh. This put her in a panic and she couldn’t stop trembling until she was reunited with her parents.

After some time at a refugee camp in Vietnam, she reached Japan in 1987 with the help of a relative. She then saved money by working at an ironworks in Hiroshima. Nine years later, she opened a restaurant so that Japanese people can become more familiar with Cambodia through her food.

Ms. Haritomi has experienced first-hand how government systems in Japan are hard on non-Japanese people, including procedures involving the pension scheme, health insurance, and Japanese citizenship. But despite her difficulties, she felt encouraged by the smiles of her customers who were happy with her dishes and told her the food is delicious. She is now planning to stay in Japan for the rest of her life. “I want to live my life with a full heart, appreciating each day,” she said. (Written by Miku Yamashita 17, Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 14, and Hinako Okada, 14)

Profile

Yuko Haritomi

In 1975, when Pol Pot seized power, she was forced to live and labor in a rural village. After her release from these conditions in 1979, she moved to a refugee camp in Vietnam and came to Japan in 1987. She opened her restaurant in Higashihiroshima in 1996.

Keywords

Civil war in Cambodia

After Lon Nol, a pro-U.S. politician, and his supporters staged a coup and created the Khmer Republic in 1970, civil war broke out between the government and Pol Pot’s forces, which sought to establish an extreme form of communism in the country. When Pol Pot seized power in 1975, many intellectuals and political prisoners were executed. Urban residents were forced to live and work in rural areas. It is said that more than 2 million people died from widespread killing and famine until the Pol Pot regime collapsed in 1979, brought on by the invasion of Vietnamese forces. Though, afterward, armed conflict persisted among four groups, the Paris Peace Accords were finally signed in 1991.

Tomoko Watanabe, executive director of Hiroshima NPO, helps build health clinic at refugee camp

One woman in Hiroshima has visited a refugee camp for Afghans in Pakistan and helped build a health clinic for the camp’s residents. Tomoko Watanabe, 62, is the executive director of ANT-Hiroshima, an NPO in Naka Ward. I interviewed her and asked about the conditions at the refugee camp. (Written by Hinako Okada, second-year junior high school student)

I’ve visited the refugee camp a total of seven times since 2002. It’s located near Peshawar, in the northern part of Pakistan. In the beginning, I found children who were made to labor amid the poverty there, such as weaving carpets, instead of getting an education. The girls would get married in their early teens and begin having children. But mothers were unable to breastfeed their babies because of their own malnutrition. Even the water that they used for powdered milk was contaminated by dirt due to drought, which caused diarrhea in the babies and toddlers.

The most pressing need was improving sanitary conditions there. A health clinic is essential for delivering babies safely and providing health education. After the atomic bombing, Hiroshima was able to rebuild and prosper once more thanks to the support of others in the world. As a second-generation A-bomb survivor myself, I wanted to do something to help them, and so I raised funds to build a health clinic at the camp.

Though the construction work on the clinic had to be suspended for a while until the Taliban were cleared from the area, the facility was finally completed in 2011. Today, the clinic is operated by a committee consisting of refugees and local residents and around 1,000 patients come to the clinic each month. I still receive monthly reports on its progress.

Key points for accepting more non-Japanese refugees in Japan

For non-Japanese people who have fled civil war in their country, what should the Japanese government and the people of Japan do? We spoke with Nami Shimonaka, 59, a lawyer from the Hiroshima Bar Association who is knowledgeable about issues involving non-Japanese refugees, and pondered how the process of accepting refugees into this country might be improved. Below is a summary of our key points. (Written by Shino Taniguchi, 17)

People should take more interest in the issue.

If Japanese citizens take more interest in this issue, the government’s negative attitude toward accepting refugees could change. Some people are stuck in seeing Japan as an island nation somehow removed from the world and are afraid that refugees and their cultures might have a negative influence on Japan. But we need to promote more mutual exchange with others. We should seek to accept their good side, and if there are any problems, we can discuss and solve them together.

Criteria for acquiring resident status should be eased.

Some refugees have returned to their home country in despair because they were not accepted by the Japanese government. And they could face persecution once they set foot in their homeland. Meanwhile, other refugees have been in Japan for more than 10 years without resident status provided by the government. For non-Japanese people, holding resident status means being recognized as a “human being” in Japan. It could be mutually beneficial if these people work in Japan and make a contribution to Japanese society.

International contributions can be made right around us.

In a sense, Japan has been contributing to the persecution of those who flee conflict in their own countries because it insists on remaining isolated and unwilling to accept many refugees. This could be considered a violation of their rights as human beings. Providing financial support to nations suffering from civil war is important, of course, but we should offer more help to non-Japanese people who are already in Japan and are having difficulty making a living here.

Junior writers’ impressions

I felt ashamed that I had taken no interest in the issue of refugees before. Some people have fled for their lives to come to Japan. I think Japanese citizens shouldn’t view this as an issue that has no connection to them and instead put more pressure on the government so that more of these people can receive resident status. (Shino Taniguchi)

Ms. Haritomi is a powerful woman with a pleasant smile. She told me that her secret of happiness is “not to worry too much.” During our interview with her, we ate the food she prepared. I went to Cambodia last year, but I thought her dishes were tastier than the food I ate there. In particular, her Vietnamese “okonomiyaki” was wonderful. The layer of crispy batter and the other ingredients, like minced meat and bean sprouts, were a perfect match. I heartily recommend that everyone go to her restaurant and try her food. (Miku Yamashita)

Until I heard Mr. Khlid’s horrific story about his past, I had thought that Japan didn’t need to take in refugees. But I was moved by the words he repeated that “Human beings are here to help one another.” His experience overlaps with the experience of the A-bomb survivors in that both abruptly lost their happy lives, though their suffering is also different. I want to pay more attention to the problems taking place in the world. (Nako Yoshimoto)

I realized that people who flee to other nations because of war or conflict are faced with harsher circumstances than I imagined. Today, Japan accepts very few refugees. And even if they are accepted by the Japanese government, they may face other difficulties such as discrimination. I think that more Japanese citizens should understand the current conditions in the world and the voices of non-Japanese people who are seeking our help. (Hinako Okada)

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds of smiles which can be spread around the world by thinking about peace and the preciousness of life from various viewpoints. To fill this world with flowering smiles, 44 junior writers from the sixth grade of elementary school to the fifth year of high school, choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on February 25, 2016)

In other parts of the world, there are people who have fled for their lives from the destruction and chaos of their war-torn homelands. In recent days, the flight of many refugees from Syria and other volatile countries to nations of the European Union (EU) has drawn worldwide attention. Because their home countries are politically unstable and unsafe, they feel no other option but to forge new lives elsewhere.

Some refugees have come as far as Japan. The number of people from other nations who have sought residency here as a “refugee” was 7,586 (preliminary figure) in 2015, which marked a record-high for the fifth consecutive year. On the other hand, the Japanese government officially recognized only 27 as refugees last year, which was 16 more than the year before. Japan is clearly not very open to taking in refugees.

Hiroshima Prefecture is now home to some refugees, too, who fled from civil war in their countries. The junior writers met with two, from Afghanistan and Cambodia, and listened to their terrible experiences of war and suffering. And we pondered what we might do, as human beings, to help others in such circumstances.

Kohi Ahmad Khlid, 35, from Afghanistan: “We’re all the same human beings.”

“Weapons have destroyed my country and my family’s lives. I want all weapons gone from this world,” said Kohi Ahmad Khlid, sharing his strong wish. Mr. Khlid, 35, is from Afghanistan and he now lives in Higashihiroshima and works for a trading company. Because of the fighting there, he barely escaped with his life, arriving in Japan 18 years ago. He understands, first-hand, how important and fragile peace really is.

When Mr. Khlid was 10, the civil war among the Mujahedeen (Islamic soldiers) grew more intense. In 1997, at the age of 16, he moved from Mazar-e-Sharif, his hometown, to Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, because the Taliban, a militant Islamic group, had approached the town.

In Kabul, he encountered a city without functional public utilities or radio and television programs, which were banned. Several months later, Mr. Khlid headed to Peshawar, a city in northern Pakistan, which neighbors Afghanistan. The city was in chaos, with local police arresting people without cause to extort money, and Taliban soldiers hiding out there. “At that point, I made up my mind to get much farther away,” he said.

In 1998, Mr. Khlid, with the help of an agent, traveled alone through Thailand to Tokyo to visit a relative in Japan, and sought help in this country.

However, at times he felt that the Japanese people around him couldn’t really understand his plight, as in the cold-hearted responses he experienced from the staff at the Immigration Bureau. He once called his mother abroad and cried, telling her, “We’re all the same human beings. Why do I have to be treated like this?”

Meanwhile, he received a job offer from a volunteer at his Japanese language class and began to take steps forward toward independence. He worked very hard as he moved to various locations and took on various kinds of work. In 2002, he became a permanent resident in Japan, then married an Afghan woman in 2008 and moved to Higashihiroshima. They now have two children.

Because his work prevented him from continuing his education or pursuing other interests, he feels strongly about gaining more education for the future. He hopes that Japan will develop an assistance program for refugees, as in other countries.

Mr. Khlid has now been living in Japan longer than the period of time he spent in Afghanistan. “I don’t have any intention of going back to my home country, which has been warped so badly by more powerful nations, and is unable to realize peace,” he said. “If people who are armed seize power, others could be killed, over simply what they say, and this could spark more war. We don’t know when our happy lives in Japan, including my own, might be lost, like in Afghanistan. So we have to create a world that’s free of weapons.” (Written by Shino Taniguchi, 17, Reiko Takaya, 17, and Nako Yoshimoto, 16)

Profile

Kohi Ahmad Khlid

Fled to Pakistan with his family in 1997 because of the Afghan civil war. In 1998, he came alone to Japan via Thailand. He has been living in Higashihiroshima since 2012.

Keywords

Afghan civil war

Insurgent groups, which received aid from the United States and other nations, fought against the military deployments made by the former Soviet Union in 1979. Even after the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan, the Mujahedeen (Islamic soldiers) fought one other to take control, and the entire country fell into disorder. In 1996, the Taliban, an Islamic militant group, seized control of the capital, Kabul, and installed its regime. Then, Al-Qaida, an international terrorist group that the Taliban had protected, staged terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, and the United States launched military operations in Afghanistan. Though the Taliban regime has collapsed, U.S. forces are still stationed there.

Yuko Haritomi, 48, from Cambodia: “The person right in front of me was killed by a bomb.”

APSARAS, a Cambodian and Vietnamese restaurant in Higashihiroshima, marked its 20th anniversary in January of this year. Yuko Haritomi (or Eap Yeuyeun, her Cambodian name), 48, the owner of the restaurant, arrived in Japan 29 years ago after fleeing from Cambodia’s civil war. “The smiles of my customers have given me emotional support for my life in Japan,” she said.

In 1975, when Ms. Haritomi lived in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, her life was turned upside down after Pol Pot and his supporters rose to power. At first, she was told to stay at a farming village for just three days, but eventually she was forced into living there. Although she was an elementary school student at the time, she was separated from her parents and made to do farm work from early morning to after sunset until the regime collapsed in 1979. She was given only two meals a day, and if she stole food or slacked off in her work, she would have been killed. “I was terrified every day,” she said.

When she was finally freed from forced labor, she was unable to walk without a cane because of malnutrition and overwork. While running away from falling bombs, the person in front of her was struck and blown into pieces of flesh. This put her in a panic and she couldn’t stop trembling until she was reunited with her parents.

After some time at a refugee camp in Vietnam, she reached Japan in 1987 with the help of a relative. She then saved money by working at an ironworks in Hiroshima. Nine years later, she opened a restaurant so that Japanese people can become more familiar with Cambodia through her food.

Ms. Haritomi has experienced first-hand how government systems in Japan are hard on non-Japanese people, including procedures involving the pension scheme, health insurance, and Japanese citizenship. But despite her difficulties, she felt encouraged by the smiles of her customers who were happy with her dishes and told her the food is delicious. She is now planning to stay in Japan for the rest of her life. “I want to live my life with a full heart, appreciating each day,” she said. (Written by Miku Yamashita 17, Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 14, and Hinako Okada, 14)

Profile

Yuko Haritomi

In 1975, when Pol Pot seized power, she was forced to live and labor in a rural village. After her release from these conditions in 1979, she moved to a refugee camp in Vietnam and came to Japan in 1987. She opened her restaurant in Higashihiroshima in 1996.

Keywords

Civil war in Cambodia

After Lon Nol, a pro-U.S. politician, and his supporters staged a coup and created the Khmer Republic in 1970, civil war broke out between the government and Pol Pot’s forces, which sought to establish an extreme form of communism in the country. When Pol Pot seized power in 1975, many intellectuals and political prisoners were executed. Urban residents were forced to live and work in rural areas. It is said that more than 2 million people died from widespread killing and famine until the Pol Pot regime collapsed in 1979, brought on by the invasion of Vietnamese forces. Though, afterward, armed conflict persisted among four groups, the Paris Peace Accords were finally signed in 1991.

Tomoko Watanabe, executive director of Hiroshima NPO, helps build health clinic at refugee camp

One woman in Hiroshima has visited a refugee camp for Afghans in Pakistan and helped build a health clinic for the camp’s residents. Tomoko Watanabe, 62, is the executive director of ANT-Hiroshima, an NPO in Naka Ward. I interviewed her and asked about the conditions at the refugee camp. (Written by Hinako Okada, second-year junior high school student)

I’ve visited the refugee camp a total of seven times since 2002. It’s located near Peshawar, in the northern part of Pakistan. In the beginning, I found children who were made to labor amid the poverty there, such as weaving carpets, instead of getting an education. The girls would get married in their early teens and begin having children. But mothers were unable to breastfeed their babies because of their own malnutrition. Even the water that they used for powdered milk was contaminated by dirt due to drought, which caused diarrhea in the babies and toddlers.

The most pressing need was improving sanitary conditions there. A health clinic is essential for delivering babies safely and providing health education. After the atomic bombing, Hiroshima was able to rebuild and prosper once more thanks to the support of others in the world. As a second-generation A-bomb survivor myself, I wanted to do something to help them, and so I raised funds to build a health clinic at the camp.

Though the construction work on the clinic had to be suspended for a while until the Taliban were cleared from the area, the facility was finally completed in 2011. Today, the clinic is operated by a committee consisting of refugees and local residents and around 1,000 patients come to the clinic each month. I still receive monthly reports on its progress.

Key points for accepting more non-Japanese refugees in Japan

For non-Japanese people who have fled civil war in their country, what should the Japanese government and the people of Japan do? We spoke with Nami Shimonaka, 59, a lawyer from the Hiroshima Bar Association who is knowledgeable about issues involving non-Japanese refugees, and pondered how the process of accepting refugees into this country might be improved. Below is a summary of our key points. (Written by Shino Taniguchi, 17)

People should take more interest in the issue.

If Japanese citizens take more interest in this issue, the government’s negative attitude toward accepting refugees could change. Some people are stuck in seeing Japan as an island nation somehow removed from the world and are afraid that refugees and their cultures might have a negative influence on Japan. But we need to promote more mutual exchange with others. We should seek to accept their good side, and if there are any problems, we can discuss and solve them together.

Criteria for acquiring resident status should be eased.

Some refugees have returned to their home country in despair because they were not accepted by the Japanese government. And they could face persecution once they set foot in their homeland. Meanwhile, other refugees have been in Japan for more than 10 years without resident status provided by the government. For non-Japanese people, holding resident status means being recognized as a “human being” in Japan. It could be mutually beneficial if these people work in Japan and make a contribution to Japanese society.

International contributions can be made right around us.

In a sense, Japan has been contributing to the persecution of those who flee conflict in their own countries because it insists on remaining isolated and unwilling to accept many refugees. This could be considered a violation of their rights as human beings. Providing financial support to nations suffering from civil war is important, of course, but we should offer more help to non-Japanese people who are already in Japan and are having difficulty making a living here.

Junior writers’ impressions

I felt ashamed that I had taken no interest in the issue of refugees before. Some people have fled for their lives to come to Japan. I think Japanese citizens shouldn’t view this as an issue that has no connection to them and instead put more pressure on the government so that more of these people can receive resident status. (Shino Taniguchi)

Ms. Haritomi is a powerful woman with a pleasant smile. She told me that her secret of happiness is “not to worry too much.” During our interview with her, we ate the food she prepared. I went to Cambodia last year, but I thought her dishes were tastier than the food I ate there. In particular, her Vietnamese “okonomiyaki” was wonderful. The layer of crispy batter and the other ingredients, like minced meat and bean sprouts, were a perfect match. I heartily recommend that everyone go to her restaurant and try her food. (Miku Yamashita)

Until I heard Mr. Khlid’s horrific story about his past, I had thought that Japan didn’t need to take in refugees. But I was moved by the words he repeated that “Human beings are here to help one another.” His experience overlaps with the experience of the A-bomb survivors in that both abruptly lost their happy lives, though their suffering is also different. I want to pay more attention to the problems taking place in the world. (Nako Yoshimoto)

I realized that people who flee to other nations because of war or conflict are faced with harsher circumstances than I imagined. Today, Japan accepts very few refugees. And even if they are accepted by the Japanese government, they may face other difficulties such as discrimination. I think that more Japanese citizens should understand the current conditions in the world and the voices of non-Japanese people who are seeking our help. (Hinako Okada)

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds of smiles which can be spread around the world by thinking about peace and the preciousness of life from various viewpoints. To fill this world with flowering smiles, 44 junior writers from the sixth grade of elementary school to the fifth year of high school, choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on February 25, 2016)