Peace Seeds: Teens in Hiroshima Sow Seeds of Peace (Part 39)

Dec. 15, 2016

Part 39: Finding traces of destroyed lives near A-bomb hypocenter

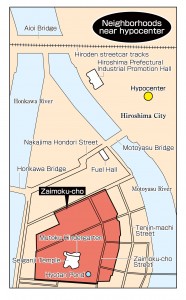

The area where the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park now lies developed as a castle town after Mori Terumoto, a feudal lord, built Hiroshima Castle at the end of the 16th century. In the time following the Meiji Era (1868-1912), this area flourished, becoming the most bustling part of Hiroshima prefecture. Many people made their homes here, alongside inns, hospitals, post offices, and large temples. The streets were lined with shops and attracted crowds of people.

But this area was also within 500 meters of the hypocenter of the atomic bombing. The people and the buildings were all annihilated in an instant.

Excavation work is now underway on the grounds of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, where there was a neighborhood known as Zaimoku-cho at the time of the atomic bombing. The junior writers had the opportunity to join this effort and we helped find the personal effects of A-bomb victims, evidence of the lives people lived before the bomb exploded. It was a place where ordinary people went about their daily lives, where children played and sometimes quarreled.

When we walk through the Peace Memorial Park, this is a reality we don’t typically recall. If we can make the lives of these people more visible, along with the scars of the bombing, this would be a powerful way to convey the preciousness of peace and the cruelty of war and the atomic bombings.

Glimpses of lives lived at the time of the A-bombing

Making use of a tool called a double-edged weeder, which looks like a scoop with its top section bent at a right angle, we dug in the ground at the back of where the Morimoto Family house once stood. We removed dirt from a charred wooden board and carefully lifted it. But it was so fragile that we could not recover the whole piece. The reverse side of the wood was not completely burned and had kept its original color. There was something white on the wood, which looked like wall material.

We also found bent nails and tiles that had turned reddish brown, which were part of the house. Pieces of decorative green tiles and pieces of a rice bowl adorned with blue lines were also unearthed. From these artifacts, we can imagine the way of life at around the time of the bombing. Many of the pieces were about the size of a 500 yen coin (26.5 millimeters in diameter). We assumed that these things were broken into pieces in the blast. We were surprised to see that the dishes they used back then were very similar to what we use today.

We were moved to find traces of the daily lives led by people many years ago, right under the ground of a park that is so familiar to us. (Yoshiko Hirata, 15, and Yukiho Saito, 14)

Excavation underway on grounds of peace museum

The excavation work on the grounds of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum began in November 2015, taking advantage of the opportunity presented by a project that involves placing seismic isolation rubber in the foundation of the building to add seismic reinforcement. The chance to study an ordinary community of modern times is a rare occasion, and this investigation is being pursued to better understand the A-bombed city.

By digging 70 to 80 centimeters into the ground, we are able to reach the layer that was the surface of the ground at the time of the atomic bombing. Among the many artifacts that have been unearthed are tea pots and cups, pieces of glass, and large items such as a well, the tiled floor of a changing room in a public bathhouse, and sewage pipes. Other artifacts, that perhaps once belonged to children, include pieces of a rice bowl with a picture of a war plane, marbles, and dolls. Through these belongings we can feel the reality of the lives that were lived at the time. We also learned that buildings were located 15 to 20 meters to the south of what is depicted on a map that shows the area prior to the bombing.

Not so deep beneath the ground on which we walk remain traces of the lives people led 71 years ago, along with the lingering scars of the atomic bombing. “Never forget that people once lived here, and that a rich history and many lives were destroyed in an instant,” said Keita Kunogi, 42, a curator at the Hiroshima City Culture Foundation. Hiroshima was once burnt ruins, but today we lead peaceful lives on the same ground. We must always remember the significance of this fact.

Melted milk bottles bring back memories to former resident

Hiromitsu Yamasako, 81, once lived right where the excavation work is now being carried out. His father made milk deliveries, and the discovery of melted milk bottles helped identify the location of his house. Hearing this news, Mr. Yamasako’s thoughts returned to his “nice neighborhood.”

Before the war, his father ran a shop, selling such things as bread and liquor. His neighbors would call him “Hiro-chan of the bread shop.” He remembers putting sticky birdlime at the end of a bamboo stick and catching big dragonflies at Hyotan Pond, which was located to the south of his house. He also sucked nectar from the azalea flowers around that pond. He and his friends would play a game similar to baseball, but hit the ball with their hands.

This happy life changed as the war conditions deteriorated. Bread and cake became scarce, and milk was rationed to households with babies or people who were ill.

Mr. Yamasako was a fifth grader at Nakajima National School when Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb. By that time, he and other children had already been relocated to Mirasaka-cho (now part of the city of Miyoshi). His parents, sister, and brother were not at home, either, and they survived.

His father came to Mirasaka-cho for him, and they returned home around September 10 of that year. They dug into the ground where their house had stood and found charred rice and books. Asked how he feels about the peace park now lying where his house was located, he said, “If even one utility pole had remained, there would be more awareness that people actually lived here.” (Miyu Okada, 15)

Little amusement for children in final days of war

Toshiko Tanaka, 78, spent her early childhood living in an inn for military personnel in Kako-machi, located to the south of Zaimoku-cho. For one year starting in April 1944, she went to Mutoku Kindergarten, on the grounds of Seiganji Temple, which stood where the peace museum now stands.

In the final days of the war, she said, there was no playground equipment at the kindergarten. Nor were any events held for the children to show dances or songs to their parents. “We had no summer vacation, no fun events,” said Ms. Tanaka. She said she enjoyed watching black turtles bask in the sun at nearby Hyotan Pond or playing in the nearby Motoyasu River.

Before the atomic bombing, she evacuated to the Ushita district, thus escaping death. While other girls died quietly, not having the energy to cry out, she suffered burns on her arm, her hair was singed, and she blacked out. A few days later, she was awakened by the stench of dead bodies.

Many ordinary people became victims of the atomic bombing. The area where the peace park now lies is one of the places where many civilians were killed. To pass down this fact to posterity, Ms. Tanaka hopes that researchers and A-bomb survivors will work together on this excavation project so that even a part of the town that lies underground can be preserved. (Yukiho Saito, 14)

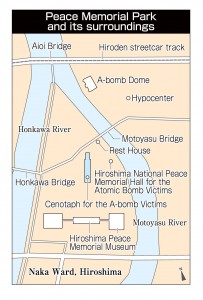

Former professor took part in research involving excavation

Norioki Ishimaru, 76, was involved in the excavation work carried out before the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims was constructed. Mr. Ishimaru, a former professor at Hiroshima University, said, “I want people to look not only at the traces of the atomic bombing, but also grasp, though these real objects, Hiroshima’s long history.” Some people who visit the Peace Memorial Park have the mistaken belief that the park was a park even before the bombing. This is why such excavation work is of importance.

If excavations are made elsewhere in the park, Mr. Ishimaru believes that artifacts will be unearthed in other places, too. He would like the excavated artifacts to be displayed in such a way that it is easy for people today to imagine the lives of those who lived at the time of the bombing. For example, he suggests that part of the excavation site be preserved and covered with tempered glass so that people can actually see it. “Linking the excavations and exhibitions of the Peace Memorial Park, visitors to the museum can then better understand the extent of the damage caused by the atomic bombing,” Mr. Ishimaru said.

Another of his ideas is to show, in the park, where the streets used to run, serving as a reminder of old communities that have since disappeared. He said this would “help people realize that there were once neighborhoods here.” (Nako Yoshimoto, 17, and Akane Sato, 14)

Junior writers’ impressions

I was impressed by the idea of covering the ruins with tempered glass to preserve and show it. I hear the chances of realizing this idea are low, but if it’s possible, future generations would be able to get a glimpse of the city at that time and feel that the atomic bombing really caused catastrophic consequences. (Shino Taniguchi)

It was good that we could interview Mr. Ishimaru, who has been involved in this excavation work. He shared with us not only his knowledge about the research but also some concrete ideas about how the unearthed artifacts should be displayed in connection with other artifacts in the Peace Memorial Museum. We must find a way to make the most of the messages those artifacts can convey. (Nako Yoshimoto)

I heard that some people mistakenly believe that the Peace Memorial Park was a park before the atomic bombing. When I was an elementary school student, I thought so, too. But I’ve come to realize that the people who once lived there have many memories of their neighborhood, just like we do when it comes to our community. (Miyu Okada)

I was surprised to learn that education at kindergartens during the war involved things that would never be possible now. Children sang war songs to raise their fighting spirit. They didn’t have the chance to play or take part in special events. It’s remarkable how the education of that time led to today’s education where we’re not restrained from doing what we want to do. (Yoshiko Hirata)

I had never thought about what lies beneath the ground of the Peace Memorial Park or what used to stand around it. But after the excavation work began, I became interested in this research. I’m glad I was able to learn about this through our work on this article. I feel moved to tell other people about what I’ve learned. (Yukiho Saito)

I never paid special attention to how people lived before the atomic bombing. But through our work on this article, I’ve come to realize that learning about what happened to Hiroshima as a result of the bombing is not the only way to learn about this subject. In the future, I’d like to hold a variety of viewpoints on the atomic bombing. (Akane Sato)

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds of smiles which can be spread around the world by seeing peace and the preciousness of life from various perspectives. To fill this world with flowering smiles, 30 junior writers, from the first year of junior high school to the third year of senior high school, choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on December 15, 2016)

The area where the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park now lies developed as a castle town after Mori Terumoto, a feudal lord, built Hiroshima Castle at the end of the 16th century. In the time following the Meiji Era (1868-1912), this area flourished, becoming the most bustling part of Hiroshima prefecture. Many people made their homes here, alongside inns, hospitals, post offices, and large temples. The streets were lined with shops and attracted crowds of people.

But this area was also within 500 meters of the hypocenter of the atomic bombing. The people and the buildings were all annihilated in an instant.

Excavation work is now underway on the grounds of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, where there was a neighborhood known as Zaimoku-cho at the time of the atomic bombing. The junior writers had the opportunity to join this effort and we helped find the personal effects of A-bomb victims, evidence of the lives people lived before the bomb exploded. It was a place where ordinary people went about their daily lives, where children played and sometimes quarreled.

When we walk through the Peace Memorial Park, this is a reality we don’t typically recall. If we can make the lives of these people more visible, along with the scars of the bombing, this would be a powerful way to convey the preciousness of peace and the cruelty of war and the atomic bombings.

Glimpses of lives lived at the time of the A-bombing

Making use of a tool called a double-edged weeder, which looks like a scoop with its top section bent at a right angle, we dug in the ground at the back of where the Morimoto Family house once stood. We removed dirt from a charred wooden board and carefully lifted it. But it was so fragile that we could not recover the whole piece. The reverse side of the wood was not completely burned and had kept its original color. There was something white on the wood, which looked like wall material.

We also found bent nails and tiles that had turned reddish brown, which were part of the house. Pieces of decorative green tiles and pieces of a rice bowl adorned with blue lines were also unearthed. From these artifacts, we can imagine the way of life at around the time of the bombing. Many of the pieces were about the size of a 500 yen coin (26.5 millimeters in diameter). We assumed that these things were broken into pieces in the blast. We were surprised to see that the dishes they used back then were very similar to what we use today.

We were moved to find traces of the daily lives led by people many years ago, right under the ground of a park that is so familiar to us. (Yoshiko Hirata, 15, and Yukiho Saito, 14)

Excavation underway on grounds of peace museum

The excavation work on the grounds of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum began in November 2015, taking advantage of the opportunity presented by a project that involves placing seismic isolation rubber in the foundation of the building to add seismic reinforcement. The chance to study an ordinary community of modern times is a rare occasion, and this investigation is being pursued to better understand the A-bombed city.

By digging 70 to 80 centimeters into the ground, we are able to reach the layer that was the surface of the ground at the time of the atomic bombing. Among the many artifacts that have been unearthed are tea pots and cups, pieces of glass, and large items such as a well, the tiled floor of a changing room in a public bathhouse, and sewage pipes. Other artifacts, that perhaps once belonged to children, include pieces of a rice bowl with a picture of a war plane, marbles, and dolls. Through these belongings we can feel the reality of the lives that were lived at the time. We also learned that buildings were located 15 to 20 meters to the south of what is depicted on a map that shows the area prior to the bombing.

Not so deep beneath the ground on which we walk remain traces of the lives people led 71 years ago, along with the lingering scars of the atomic bombing. “Never forget that people once lived here, and that a rich history and many lives were destroyed in an instant,” said Keita Kunogi, 42, a curator at the Hiroshima City Culture Foundation. Hiroshima was once burnt ruins, but today we lead peaceful lives on the same ground. We must always remember the significance of this fact.

Melted milk bottles bring back memories to former resident

Hiromitsu Yamasako, 81, once lived right where the excavation work is now being carried out. His father made milk deliveries, and the discovery of melted milk bottles helped identify the location of his house. Hearing this news, Mr. Yamasako’s thoughts returned to his “nice neighborhood.”

Before the war, his father ran a shop, selling such things as bread and liquor. His neighbors would call him “Hiro-chan of the bread shop.” He remembers putting sticky birdlime at the end of a bamboo stick and catching big dragonflies at Hyotan Pond, which was located to the south of his house. He also sucked nectar from the azalea flowers around that pond. He and his friends would play a game similar to baseball, but hit the ball with their hands.

This happy life changed as the war conditions deteriorated. Bread and cake became scarce, and milk was rationed to households with babies or people who were ill.

Mr. Yamasako was a fifth grader at Nakajima National School when Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb. By that time, he and other children had already been relocated to Mirasaka-cho (now part of the city of Miyoshi). His parents, sister, and brother were not at home, either, and they survived.

His father came to Mirasaka-cho for him, and they returned home around September 10 of that year. They dug into the ground where their house had stood and found charred rice and books. Asked how he feels about the peace park now lying where his house was located, he said, “If even one utility pole had remained, there would be more awareness that people actually lived here.” (Miyu Okada, 15)

Little amusement for children in final days of war

Toshiko Tanaka, 78, spent her early childhood living in an inn for military personnel in Kako-machi, located to the south of Zaimoku-cho. For one year starting in April 1944, she went to Mutoku Kindergarten, on the grounds of Seiganji Temple, which stood where the peace museum now stands.

In the final days of the war, she said, there was no playground equipment at the kindergarten. Nor were any events held for the children to show dances or songs to their parents. “We had no summer vacation, no fun events,” said Ms. Tanaka. She said she enjoyed watching black turtles bask in the sun at nearby Hyotan Pond or playing in the nearby Motoyasu River.

Before the atomic bombing, she evacuated to the Ushita district, thus escaping death. While other girls died quietly, not having the energy to cry out, she suffered burns on her arm, her hair was singed, and she blacked out. A few days later, she was awakened by the stench of dead bodies.

Many ordinary people became victims of the atomic bombing. The area where the peace park now lies is one of the places where many civilians were killed. To pass down this fact to posterity, Ms. Tanaka hopes that researchers and A-bomb survivors will work together on this excavation project so that even a part of the town that lies underground can be preserved. (Yukiho Saito, 14)

Former professor took part in research involving excavation

Norioki Ishimaru, 76, was involved in the excavation work carried out before the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims was constructed. Mr. Ishimaru, a former professor at Hiroshima University, said, “I want people to look not only at the traces of the atomic bombing, but also grasp, though these real objects, Hiroshima’s long history.” Some people who visit the Peace Memorial Park have the mistaken belief that the park was a park even before the bombing. This is why such excavation work is of importance.

If excavations are made elsewhere in the park, Mr. Ishimaru believes that artifacts will be unearthed in other places, too. He would like the excavated artifacts to be displayed in such a way that it is easy for people today to imagine the lives of those who lived at the time of the bombing. For example, he suggests that part of the excavation site be preserved and covered with tempered glass so that people can actually see it. “Linking the excavations and exhibitions of the Peace Memorial Park, visitors to the museum can then better understand the extent of the damage caused by the atomic bombing,” Mr. Ishimaru said.

Another of his ideas is to show, in the park, where the streets used to run, serving as a reminder of old communities that have since disappeared. He said this would “help people realize that there were once neighborhoods here.” (Nako Yoshimoto, 17, and Akane Sato, 14)

Junior writers’ impressions

I was impressed by the idea of covering the ruins with tempered glass to preserve and show it. I hear the chances of realizing this idea are low, but if it’s possible, future generations would be able to get a glimpse of the city at that time and feel that the atomic bombing really caused catastrophic consequences. (Shino Taniguchi)

It was good that we could interview Mr. Ishimaru, who has been involved in this excavation work. He shared with us not only his knowledge about the research but also some concrete ideas about how the unearthed artifacts should be displayed in connection with other artifacts in the Peace Memorial Museum. We must find a way to make the most of the messages those artifacts can convey. (Nako Yoshimoto)

I heard that some people mistakenly believe that the Peace Memorial Park was a park before the atomic bombing. When I was an elementary school student, I thought so, too. But I’ve come to realize that the people who once lived there have many memories of their neighborhood, just like we do when it comes to our community. (Miyu Okada)

I was surprised to learn that education at kindergartens during the war involved things that would never be possible now. Children sang war songs to raise their fighting spirit. They didn’t have the chance to play or take part in special events. It’s remarkable how the education of that time led to today’s education where we’re not restrained from doing what we want to do. (Yoshiko Hirata)

I had never thought about what lies beneath the ground of the Peace Memorial Park or what used to stand around it. But after the excavation work began, I became interested in this research. I’m glad I was able to learn about this through our work on this article. I feel moved to tell other people about what I’ve learned. (Yukiho Saito)

I never paid special attention to how people lived before the atomic bombing. But through our work on this article, I’ve come to realize that learning about what happened to Hiroshima as a result of the bombing is not the only way to learn about this subject. In the future, I’d like to hold a variety of viewpoints on the atomic bombing. (Akane Sato)

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds of smiles which can be spread around the world by seeing peace and the preciousness of life from various perspectives. To fill this world with flowering smiles, 30 junior writers, from the first year of junior high school to the third year of senior high school, choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on December 15, 2016)