Peace Seeds: Teens in Hiroshima Sow Seeds of Peace (Part 58)

Jul. 19, 2018

Part 58: Reciting accounts of the atomic bombing

Opportunities to directly listen to those who experienced the atomic bombing are declining. Amid such circumstances, one of the key activities for learning about the atomic bombing is the use of A-bomb accounts.

Recently, efforts to recite the A-bomb accounts written by survivors or family members have been spreading. The times when the accounts were written, the ages of those who wrote them, and the places where they were when the atomic bomb was dropped, these details vary from person to person. When people recite these accounts, reading them aloud to convey the content, this can enable listeners to imagine that tragic time and empathize with the sorrow and anger felt by the survivors and family members.

The junior writers of the Chugoku Shimbun attended a program of readings about the atomic bombing and had the chance to read out some accounts. We went through a lot of other accounts, too, and chose some that we would like people to recite and share with others.

Volunteers convey the day of the atomic bombing

Eriko Amimoto, 65, is a recitation volunteer at the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, located in Naka Ward. Ms. Amimoto organized the program and four junior writers took part. Each of us recited the A-bomb accounts that we had selected in advance.

I read the account written by Masako Maeda, who experienced the atomic bombing when she was an elementary school student. Her account was published in Honkawa Chiku Hibakutaikenshu (A Collection of Accounts about the A-bombing in the Honkawa District) and includes these words: “When I went out, I heard the sounds of a crowd. Everything looked totally different from when I went to my school in the morning. I heard people crying out, saying, ‘Help me! Give me water! It’s so hot!’ There was a mass of people.”

I put my heart into reading each sentence, but I was too preoccupied with technical things like how to pause and how to maintain the sort of tempo I had learned in the broadcasting club at my school. Then Ms. Amimoto said, “If you stumble over your words or your voice sounds hoarse, that’s okay. The most important thing when conveying the account is your feelings behind the message you’re sending.”

She also said, however, that it was important not to be too dramatic or be moved to tears while reading. The feelings of the listeners are what matters most, and those who are reciting the accounts should read in a straightforward way, maintaining control over their feelings. To convey the accounts effectively, it is necessary to understand the meaning of words that were used during the war, such as “student mobilization,” and check the kanji readings of place names.

I felt sorry that I wasn’t able to fully convey the suffering of those who experienced the atomic bombing each time I recited an account. Ms. Amimoto stressed, “The power of reciting these accounts is that the readers and listeners can stretch their imagination through the use of the human voice.” If we simply read the accounts ourselves, it’s harder to get a deeper understanding of the situations or feelings of the people who wrote them. But when there are readers and listeners, I think all the participants can better grasp the feelings of those who experienced the atomic bombing through their words. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

A-bomb accounts at the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

A-bomb accounts are recited each month at the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims. On the day of our interviews, in June, three volunteers were reciting A-bomb accounts and A-bomb poems.

Before the recitations began, Akira Katayama, 82, who led the event, told the listeners not to open the books before them because he wanted them to feel the accounts by listening to them, not by looking at the words on the page.

I listened intently, and I felt as if such words like “Good morning” or “Help me” were being directed to me. From the reader’s expression and gestures, I was also able to vividly imagine the situation at that time.

Kazuya Nagasawa, 20, a freshman at Hiroshima University and a resident of the city of Higashihiroshima, was attending a recitation for the first time. He said, “Many people see images of war in animated movies and video games and think that war is cool. They should come to one of these readings and understand the real horror and tragedy of war.” We are able to learn about the reality of war more directly and closely when people are reciting the A-bomb accounts. I hope that you will take part in a recitation, too. (Akane Sato, 15)

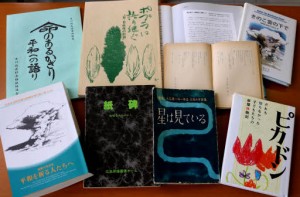

10 A-bomb accounts chosen by junior writers

We looked through collections of A-bomb accounts compiled by schools, districts, and businesses and chose 10 accounts that moved us and enabled us to imagine the horrific conditions of the atomic bombing. We hope that you will try reading aloud these accounts, too.

1. Heiwa wo Inoru Hitotachi e (To Those Who Pray for Peace) (Hiroshima Jogakuin alumni association, 2015)

Mitsuko Koshimizu was in the back row of the morning meeting at Hiroshima Jogakuin Senmon Gakko (now Hiroshima Jogakuin University) and managed to survive the A-bomb attack.

Excerpt: “My friend got pinned down and couldn’t escape. ‘Please help me!’ she cried. ‘Please cut off my legs!’ She was crying out for her life.”

Comment: Her description of the aftermath of the bombing enabled me to feel how destructive the atomic bomb was. (Aoi Nakagawa, 17)

2. Honkawa Chiku Hibakutaikenshu Inochi no Arukagiri Heiwa eno Inori (A Collection of Accounts about A-bomb Experiences in the Honkawa District, Prayers for Peace as Long as We Live) (Welfare Division of the Honkawa District of Social Welfare, 2007)

Masako Maeda was studying by herself and managed to escape through a hole in the wall.

Excerpt: “In an instant, I lost everything. I didn’t feel anything. I might have lost my mind, too.”

Comment: When I recite this account, I can feel the tension and imagine the sounds that she experienced that day. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

3. Shihi Hibaku Rojin no Akashi (Paper Monument: The Testimonies of Aging A-bomb Survivors) (The Hiroshima A-bomb Survivors Relief Foundation, 1981)

Komura Takemori was unable to find the remains of her 17-year-old and 14-year-old daughters.

Excerpt: “There were mountains of rubble all over the city. Some people were working hard to dispose of the dead bodies. Others, like us, were walking around, searching for our relatives. There was no public transportation.”

Comment: I was able to imagine the scenes of that time through the straightforward way that she wrote about her horrific experiences. (Akane Sato, 15)

4. Hiroshima Dentetsu Kaigyo 80 / Soritsu 50 Nenshi (Hiroshima Electric Railway Company 80 / 50th Anniversary of the Company’s Founding) (Hiroshima Electric Railways Company, 1992)

Haruno Horimoto worked as a conductor on the first streetcar that ran in the aftermath of the bombing, three days after the disaster.

Excerpt: I was going out to search for my mother again when a teacher asked, “The streetcar will start running again today. Can someone help by serving as a conductor?”

Comment: I was surprised that young people of the same age as us put priority on working at that time. (Yukiko Ouchi, 14)

5. Zenmetsu Shita Hiroshima Icchu Ichinensei, Fubo no Shukishu: Hoshi wa Miteiru (All the First-Year Students at Hiroshima First Middle School Were Killed by the A-bomb, A Collection of Memoirs Written by their Fathers and Mothers: The Twinkling Stars Know Everything) (1954)

Masayuki Akita lost his eldest son, who had been mobilized to help tear down homes to create a fire lane.

Excerpt: “‘I’m sorry, Mother. I’m sorry, Father. At first, about 40 or 50 people were coming back, encouraging each other, but when I turned back and looked at Asahi Bridge, there were only 14 people,’ Koso said faintly. ‘Everyone has died.’”

Comment: From his words, I can feel his sorrow and emptiness. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

6. Pupura wa Kataritsugu: 8.6 Zengo no Kiroku (Poplar Trees Hand Down Records of Before and After August 6) (The 23rd Students at Second Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Junior High School, 1991)

Mitsuo Yamamoto, a second-year student, suffered wounds to his face while working at the East Drill Ground as a mobilized student.

Excerpt: “I heard neighbors say, ‘He’s alive, but his face…’ I cried out in despair, ‘Mom, I want to die!’ Tears got into my wounds, and made the pain even worse. My mother was crying as she said to me, ‘Even if there are scars, you have to go on.’”

Comment: When I read this account, I felt the deep love that this mother felt for her child. (Atsuhito Ito, 15)

7. Genshigumo no Shita yori (From Under the Mushroom Cloud) (Compiled by Sankichi Toge and Tomoe Yamashiro in 1952)

Takako Tokuzawa wrote a poem about the atomic bombing when she was a first-year student in junior high school.

Excerpt: On the morning of August 6 / When she went out, she said in a bright voice / “Takabo, I’m going.” / But / I wonder where she went. She has never come back and / seven years have passed / but she still hasn’t returned.

Comment: This is part of a poem that enables me to understand how people’s daily lives were destroyed so suddenly. (Honoka Hiramatsu, 15)

8. Kinokogumo no Shita de 1945.8.6 Hiroshima (Under the Mushroom Cloud: A Testimony of the Atomic Bombing 60 Years Later) (2005)

Yoshiko Shigetaka, a first-year student at a girls’ high school, experienced the atomic bombing while weeding at the East Drill Ground.

Excerpt: “Then shouted in a strange voice, ‘Mommy! Mommy!’ Yelling at the top of her voice, she abruptly collapsed. The room became silent. No one moved before some time. Then sobs could be heard here and there around the room.”

Comment: The accounts in this book have been translated into English, too, so people overseas can also think about what happened on that day. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

9. Pikadon: Daremo Shiranakatta Kodomotachi no Genbaku Taikenki (Pikadon: Children’s Accounts of the A-bombing Nobody Knew) (Edited by Kodansha, 2003)

Takatoshi Saeki wrote his A-bomb account when he was in the sixth grade of elementary school.

Excerpt: “There was a flash of yellow light, and everything around me looked yellow. We were frightened and we ran into the bomb shelter. Then I heard a tremendous boom.”

Comment: This account makes me feel how a child felt at the moment the atomic bomb exploded. (Hitoha Katsura, 13)

10. Hibaku Nanaju Shunen Irei no Ki Akashi (Memorial Accounts for the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: Testimonies) (Alumni associations of Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School and Funairi High School, 2015)

Reiko Hayashi experienced the atomic bombing while having breakfast with her family at the age of four and was rescued.

Excerpt: “We’ll never forget what happened on that day, and we’ll continue to convey this to others and tell about the passionate lives that you had led. I hope you will now watch over the students of the 21st century, our school, this city, and this country.”

Comment: We can take a step closer to their determination to convey their messages. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds of smiles which can be spread around the world by thinking about peace and the preciousness of life from various viewpoints. To fill this world with flowering smiles, the junior writers — 25 junior high school and senior high school students — choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on July 19, 2018)

Opportunities to directly listen to those who experienced the atomic bombing are declining. Amid such circumstances, one of the key activities for learning about the atomic bombing is the use of A-bomb accounts.

Recently, efforts to recite the A-bomb accounts written by survivors or family members have been spreading. The times when the accounts were written, the ages of those who wrote them, and the places where they were when the atomic bomb was dropped, these details vary from person to person. When people recite these accounts, reading them aloud to convey the content, this can enable listeners to imagine that tragic time and empathize with the sorrow and anger felt by the survivors and family members.

The junior writers of the Chugoku Shimbun attended a program of readings about the atomic bombing and had the chance to read out some accounts. We went through a lot of other accounts, too, and chose some that we would like people to recite and share with others.

Volunteers convey the day of the atomic bombing

Eriko Amimoto, 65, is a recitation volunteer at the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, located in Naka Ward. Ms. Amimoto organized the program and four junior writers took part. Each of us recited the A-bomb accounts that we had selected in advance.

I read the account written by Masako Maeda, who experienced the atomic bombing when she was an elementary school student. Her account was published in Honkawa Chiku Hibakutaikenshu (A Collection of Accounts about the A-bombing in the Honkawa District) and includes these words: “When I went out, I heard the sounds of a crowd. Everything looked totally different from when I went to my school in the morning. I heard people crying out, saying, ‘Help me! Give me water! It’s so hot!’ There was a mass of people.”

I put my heart into reading each sentence, but I was too preoccupied with technical things like how to pause and how to maintain the sort of tempo I had learned in the broadcasting club at my school. Then Ms. Amimoto said, “If you stumble over your words or your voice sounds hoarse, that’s okay. The most important thing when conveying the account is your feelings behind the message you’re sending.”

She also said, however, that it was important not to be too dramatic or be moved to tears while reading. The feelings of the listeners are what matters most, and those who are reciting the accounts should read in a straightforward way, maintaining control over their feelings. To convey the accounts effectively, it is necessary to understand the meaning of words that were used during the war, such as “student mobilization,” and check the kanji readings of place names.

I felt sorry that I wasn’t able to fully convey the suffering of those who experienced the atomic bombing each time I recited an account. Ms. Amimoto stressed, “The power of reciting these accounts is that the readers and listeners can stretch their imagination through the use of the human voice.” If we simply read the accounts ourselves, it’s harder to get a deeper understanding of the situations or feelings of the people who wrote them. But when there are readers and listeners, I think all the participants can better grasp the feelings of those who experienced the atomic bombing through their words. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

A-bomb accounts at the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

A-bomb accounts are recited each month at the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims. On the day of our interviews, in June, three volunteers were reciting A-bomb accounts and A-bomb poems.

Before the recitations began, Akira Katayama, 82, who led the event, told the listeners not to open the books before them because he wanted them to feel the accounts by listening to them, not by looking at the words on the page.

I listened intently, and I felt as if such words like “Good morning” or “Help me” were being directed to me. From the reader’s expression and gestures, I was also able to vividly imagine the situation at that time.

Kazuya Nagasawa, 20, a freshman at Hiroshima University and a resident of the city of Higashihiroshima, was attending a recitation for the first time. He said, “Many people see images of war in animated movies and video games and think that war is cool. They should come to one of these readings and understand the real horror and tragedy of war.” We are able to learn about the reality of war more directly and closely when people are reciting the A-bomb accounts. I hope that you will take part in a recitation, too. (Akane Sato, 15)

10 A-bomb accounts chosen by junior writers

We looked through collections of A-bomb accounts compiled by schools, districts, and businesses and chose 10 accounts that moved us and enabled us to imagine the horrific conditions of the atomic bombing. We hope that you will try reading aloud these accounts, too.

1. Heiwa wo Inoru Hitotachi e (To Those Who Pray for Peace) (Hiroshima Jogakuin alumni association, 2015)

Mitsuko Koshimizu was in the back row of the morning meeting at Hiroshima Jogakuin Senmon Gakko (now Hiroshima Jogakuin University) and managed to survive the A-bomb attack.

Excerpt: “My friend got pinned down and couldn’t escape. ‘Please help me!’ she cried. ‘Please cut off my legs!’ She was crying out for her life.”

Comment: Her description of the aftermath of the bombing enabled me to feel how destructive the atomic bomb was. (Aoi Nakagawa, 17)

2. Honkawa Chiku Hibakutaikenshu Inochi no Arukagiri Heiwa eno Inori (A Collection of Accounts about A-bomb Experiences in the Honkawa District, Prayers for Peace as Long as We Live) (Welfare Division of the Honkawa District of Social Welfare, 2007)

Masako Maeda was studying by herself and managed to escape through a hole in the wall.

Excerpt: “In an instant, I lost everything. I didn’t feel anything. I might have lost my mind, too.”

Comment: When I recite this account, I can feel the tension and imagine the sounds that she experienced that day. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

3. Shihi Hibaku Rojin no Akashi (Paper Monument: The Testimonies of Aging A-bomb Survivors) (The Hiroshima A-bomb Survivors Relief Foundation, 1981)

Komura Takemori was unable to find the remains of her 17-year-old and 14-year-old daughters.

Excerpt: “There were mountains of rubble all over the city. Some people were working hard to dispose of the dead bodies. Others, like us, were walking around, searching for our relatives. There was no public transportation.”

Comment: I was able to imagine the scenes of that time through the straightforward way that she wrote about her horrific experiences. (Akane Sato, 15)

4. Hiroshima Dentetsu Kaigyo 80 / Soritsu 50 Nenshi (Hiroshima Electric Railway Company 80 / 50th Anniversary of the Company’s Founding) (Hiroshima Electric Railways Company, 1992)

Haruno Horimoto worked as a conductor on the first streetcar that ran in the aftermath of the bombing, three days after the disaster.

Excerpt: I was going out to search for my mother again when a teacher asked, “The streetcar will start running again today. Can someone help by serving as a conductor?”

Comment: I was surprised that young people of the same age as us put priority on working at that time. (Yukiko Ouchi, 14)

5. Zenmetsu Shita Hiroshima Icchu Ichinensei, Fubo no Shukishu: Hoshi wa Miteiru (All the First-Year Students at Hiroshima First Middle School Were Killed by the A-bomb, A Collection of Memoirs Written by their Fathers and Mothers: The Twinkling Stars Know Everything) (1954)

Masayuki Akita lost his eldest son, who had been mobilized to help tear down homes to create a fire lane.

Excerpt: “‘I’m sorry, Mother. I’m sorry, Father. At first, about 40 or 50 people were coming back, encouraging each other, but when I turned back and looked at Asahi Bridge, there were only 14 people,’ Koso said faintly. ‘Everyone has died.’”

Comment: From his words, I can feel his sorrow and emptiness. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

6. Pupura wa Kataritsugu: 8.6 Zengo no Kiroku (Poplar Trees Hand Down Records of Before and After August 6) (The 23rd Students at Second Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Junior High School, 1991)

Mitsuo Yamamoto, a second-year student, suffered wounds to his face while working at the East Drill Ground as a mobilized student.

Excerpt: “I heard neighbors say, ‘He’s alive, but his face…’ I cried out in despair, ‘Mom, I want to die!’ Tears got into my wounds, and made the pain even worse. My mother was crying as she said to me, ‘Even if there are scars, you have to go on.’”

Comment: When I read this account, I felt the deep love that this mother felt for her child. (Atsuhito Ito, 15)

7. Genshigumo no Shita yori (From Under the Mushroom Cloud) (Compiled by Sankichi Toge and Tomoe Yamashiro in 1952)

Takako Tokuzawa wrote a poem about the atomic bombing when she was a first-year student in junior high school.

Excerpt: On the morning of August 6 / When she went out, she said in a bright voice / “Takabo, I’m going.” / But / I wonder where she went. She has never come back and / seven years have passed / but she still hasn’t returned.

Comment: This is part of a poem that enables me to understand how people’s daily lives were destroyed so suddenly. (Honoka Hiramatsu, 15)

8. Kinokogumo no Shita de 1945.8.6 Hiroshima (Under the Mushroom Cloud: A Testimony of the Atomic Bombing 60 Years Later) (2005)

Yoshiko Shigetaka, a first-year student at a girls’ high school, experienced the atomic bombing while weeding at the East Drill Ground.

Excerpt: “Then shouted in a strange voice, ‘Mommy! Mommy!’ Yelling at the top of her voice, she abruptly collapsed. The room became silent. No one moved before some time. Then sobs could be heard here and there around the room.”

Comment: The accounts in this book have been translated into English, too, so people overseas can also think about what happened on that day. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

9. Pikadon: Daremo Shiranakatta Kodomotachi no Genbaku Taikenki (Pikadon: Children’s Accounts of the A-bombing Nobody Knew) (Edited by Kodansha, 2003)

Takatoshi Saeki wrote his A-bomb account when he was in the sixth grade of elementary school.

Excerpt: “There was a flash of yellow light, and everything around me looked yellow. We were frightened and we ran into the bomb shelter. Then I heard a tremendous boom.”

Comment: This account makes me feel how a child felt at the moment the atomic bomb exploded. (Hitoha Katsura, 13)

10. Hibaku Nanaju Shunen Irei no Ki Akashi (Memorial Accounts for the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: Testimonies) (Alumni associations of Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School and Funairi High School, 2015)

Reiko Hayashi experienced the atomic bombing while having breakfast with her family at the age of four and was rescued.

Excerpt: “We’ll never forget what happened on that day, and we’ll continue to convey this to others and tell about the passionate lives that you had led. I hope you will now watch over the students of the 21st century, our school, this city, and this country.”

Comment: We can take a step closer to their determination to convey their messages. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds of smiles which can be spread around the world by thinking about peace and the preciousness of life from various viewpoints. To fill this world with flowering smiles, the junior writers — 25 junior high school and senior high school students — choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on July 19, 2018)