Junior Writers Reporting: Amid coronavirus pandemic, Peace Memorial Ceremony is downsized, but prayers for consoling A-bomb victims are eternal

Jul. 27, 2020

This year, the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings, Hiroshima reaches a milestone. It was once said that no grass or tree would grow in Hiroshima, but it has recovered and been reborn as a city of peace. To prevent spread of the coronavirus, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony, held annually on August 6 by Hiroshima City at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, located in the city’s Naka Ward, will be scaled back this year. As junior writers, we herein report on how the ceremony will be held this year and consider what can be done to remember A-bomb victims as an abiding wish for peace.

This year’s ceremony will be markedly different from what is typically seen every year. We interviewed Takayuki Yamane, director of the Citizens Activities Promotion Division of the Hiroshima City government, at Peace Memorial Park, which was about to begin preparations for setting up the ceremony venue.

Mr. Yamane indicated that the city had a particularly strong desire to convey its message of peace to the world this year, the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing. The staff in charge of the ceremony explored various methods to both prevent the spread of COVID-19 and successfully hold the ceremony. After the national government’s state-of-emergency declaration was lifted at the end of May, officials began to determine in earnest the plan for this year’s ceremony.

The city intends to hold this year’s ceremony as close as possible to typical ceremonies, while faithfully preserving the three missions incorporated in the ceremony: to console the souls of A-bomb victims, to pray for peace, and to convey A-bombing memories to following generations. Tubular steel folding chairs are densely laid out on the lawn area at the park each year, but for this year’s ceremony it was determined to place the seats at a distance of two meters apart. As a result, only 880 chairs will be set up in the area, accounting for 10 percent of the total number of chairs typically prepared.

With general admission seats eliminated, only the people who have been predefined as primary invited guests will attend the ceremony, including government representatives and a certain number of A-bomb survivors. The guests will be asked to disinfect their hands and have their temperatures checked at the entrance. Not making an appearance at this year’s ceremony are the chorus involving around 600 people, the ensemble performance, and the release of doves.

Mr. Yamane said, “We are sorry that many people cannot attend this year’s ceremony on site, but we hope they do what they can do individually instead,” calling for people to watch the ceremony on television or in the video posted on YouTube, an online video platform.

“It’s a milestone year, and I therefore wanted people around the world to come and attend the ceremony.”

What feelings do A-bomb survivors have about this year’s August 6 on the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing? Toshiko Kajimoto, 89, an A-bomb survivor living in Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, shared her feelings with us, including what she had experienced at the time of the atomic bombing.

Ms. Kajimoto has attended the ceremony almost every year since 2001, the time at which she began to share her A-bombing experience with others. Becoming elderly, she stopped visiting the venue in person two years ago, but she told us that she would watch the television broadcast of the ceremony this year “with a feeling as if I were in attendance with the other guests.”

Ms. Kajimoto was 14 and a third-year student at Yasuda Girls’ High School (now Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School) when she experienced the atomic bombing at a factory in Misasa-machi (now part of Nishi Ward), where she had been mobilized to work. After she regained consciousness and managed to get outside, she smelled a horrible odor. Although smeared with her own blood, she put her unmoving friends on stretchers and repeatedly carried them to Oshiba Park, located to the north of the factory.

The park was occupied with the wounded, whose bodies were lined up like fish at market. It was a scene she has tried but failed to forget.

Her father came to find her, but he died a year and a half after the bombing. Her mother was frequently in and out of the hospital. With that, Ms. Kajimoto had to support her family by herself, a painful memory for her. Nevertheless, in the early morning on August 6, before the ceremony began, she and her husband together would visit the Cenotaph for the A-bomb victims to pray. She said, “On that day, I want to quietly and deeply contemplate those who died.”

After her husband died 20 years ago, she began to recount her A-bombing experience to the public, something she was encouraged to do by her grandchild. She also started attending the Peace Memorial Ceremony. Regarding this year’s scaled-down ceremony, “I understand it can’t be helped, but I wanted people around the world to attend the ceremony because this is a milestone year,” she said. For that reason, she hopes the Hiroshima mayor, in his Peace Declaration at the ceremony, delivers a powerful message to people inside and outside Japan seeking the elimination of nuclear weapons.

She also has high expectations for efforts made by teenagers to convey the real circumstances of the atomic bombings to others by utilizing their strong suits such as drama or visual art. She offered words of encouragement. “I hope you learn a lot and make efforts to realize a peaceful world.”

Even though attending the ceremony on site is impossible this year, people can still express compassion for those who died or had painful experiences due to the atomic bombings. We thought about what we could do, while listening through online video conferencing to advice from Satoru Ubuki, 73, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University and resident of the town of Kure who is familiar with the history of the ceremony.

While Mr. Ubuki undertook study of the ceremony’s history in detail, he found that events other than the main ceremony began to become more diversified. In addition to the annual memorial events such as the paper-lantern floating on the Motoyasu River, other gatherings increased, including those planned by artists and those oriented toward participation by young people.

Such events are normally held around August 6 but a smaller number will take place this year to prevent the spread of COVID-19 based on avoidance of the three C’s: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings. Mr. Ubuki said, “I’m worried that even interesting events such as these might disappear in the future.”

On the other hand, he proposed that we “take interest in the peace events held at places close to you, such as schools or workplaces. Anyone is able to offer a silent prayer wherever he or she is at the time.” He added, “Since it has become difficult to do things you have taken for granted to this point, now is a chance to thoroughly consider what you can do yourself to console the souls of A-bomb victims.”

Reporting was carried out by the following junior writers: Atsuhito Ito, 17, Airi Shono, 17, Haruka Oikawa, 17, Yuri Furohashi, 16, Hitoha Katsura, 15, Yuna Okajima, 13, Haruka Shitanda, 16, Yuno Nakashima, 14, Aoi Miki, 15, Chihiro Yamase, 13, Jo Takeda 14, Mirei Mori, 13, Mayu Yoshida, 12, Manami Nakano, 12, and Riko Soma, 12.

(Originally published on July 27, 2020)

Consideration of ceremony operations

Achieving both prevention of virus and three missions

This year’s ceremony will be markedly different from what is typically seen every year. We interviewed Takayuki Yamane, director of the Citizens Activities Promotion Division of the Hiroshima City government, at Peace Memorial Park, which was about to begin preparations for setting up the ceremony venue.

Mr. Yamane indicated that the city had a particularly strong desire to convey its message of peace to the world this year, the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing. The staff in charge of the ceremony explored various methods to both prevent the spread of COVID-19 and successfully hold the ceremony. After the national government’s state-of-emergency declaration was lifted at the end of May, officials began to determine in earnest the plan for this year’s ceremony.

The city intends to hold this year’s ceremony as close as possible to typical ceremonies, while faithfully preserving the three missions incorporated in the ceremony: to console the souls of A-bomb victims, to pray for peace, and to convey A-bombing memories to following generations. Tubular steel folding chairs are densely laid out on the lawn area at the park each year, but for this year’s ceremony it was determined to place the seats at a distance of two meters apart. As a result, only 880 chairs will be set up in the area, accounting for 10 percent of the total number of chairs typically prepared.

With general admission seats eliminated, only the people who have been predefined as primary invited guests will attend the ceremony, including government representatives and a certain number of A-bomb survivors. The guests will be asked to disinfect their hands and have their temperatures checked at the entrance. Not making an appearance at this year’s ceremony are the chorus involving around 600 people, the ensemble performance, and the release of doves.

Mr. Yamane said, “We are sorry that many people cannot attend this year’s ceremony on site, but we hope they do what they can do individually instead,” calling for people to watch the ceremony on television or in the video posted on YouTube, an online video platform.

One A-bomb survivor’s feelings

“It’s a milestone year, and I therefore wanted people around the world to come and attend the ceremony.”

What feelings do A-bomb survivors have about this year’s August 6 on the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing? Toshiko Kajimoto, 89, an A-bomb survivor living in Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, shared her feelings with us, including what she had experienced at the time of the atomic bombing.

Ms. Kajimoto has attended the ceremony almost every year since 2001, the time at which she began to share her A-bombing experience with others. Becoming elderly, she stopped visiting the venue in person two years ago, but she told us that she would watch the television broadcast of the ceremony this year “with a feeling as if I were in attendance with the other guests.”

Ms. Kajimoto was 14 and a third-year student at Yasuda Girls’ High School (now Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School) when she experienced the atomic bombing at a factory in Misasa-machi (now part of Nishi Ward), where she had been mobilized to work. After she regained consciousness and managed to get outside, she smelled a horrible odor. Although smeared with her own blood, she put her unmoving friends on stretchers and repeatedly carried them to Oshiba Park, located to the north of the factory.

The park was occupied with the wounded, whose bodies were lined up like fish at market. It was a scene she has tried but failed to forget.

Her father came to find her, but he died a year and a half after the bombing. Her mother was frequently in and out of the hospital. With that, Ms. Kajimoto had to support her family by herself, a painful memory for her. Nevertheless, in the early morning on August 6, before the ceremony began, she and her husband together would visit the Cenotaph for the A-bomb victims to pray. She said, “On that day, I want to quietly and deeply contemplate those who died.”

After her husband died 20 years ago, she began to recount her A-bombing experience to the public, something she was encouraged to do by her grandchild. She also started attending the Peace Memorial Ceremony. Regarding this year’s scaled-down ceremony, “I understand it can’t be helped, but I wanted people around the world to attend the ceremony because this is a milestone year,” she said. For that reason, she hopes the Hiroshima mayor, in his Peace Declaration at the ceremony, delivers a powerful message to people inside and outside Japan seeking the elimination of nuclear weapons.

She also has high expectations for efforts made by teenagers to convey the real circumstances of the atomic bombings to others by utilizing their strong suits such as drama or visual art. She offered words of encouragement. “I hope you learn a lot and make efforts to realize a peaceful world.”

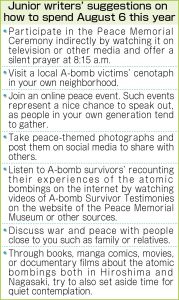

How we should spend time on August 6

First, take interest in local events

Even though attending the ceremony on site is impossible this year, people can still express compassion for those who died or had painful experiences due to the atomic bombings. We thought about what we could do, while listening through online video conferencing to advice from Satoru Ubuki, 73, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University and resident of the town of Kure who is familiar with the history of the ceremony.

While Mr. Ubuki undertook study of the ceremony’s history in detail, he found that events other than the main ceremony began to become more diversified. In addition to the annual memorial events such as the paper-lantern floating on the Motoyasu River, other gatherings increased, including those planned by artists and those oriented toward participation by young people.

Such events are normally held around August 6 but a smaller number will take place this year to prevent the spread of COVID-19 based on avoidance of the three C’s: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings. Mr. Ubuki said, “I’m worried that even interesting events such as these might disappear in the future.”

On the other hand, he proposed that we “take interest in the peace events held at places close to you, such as schools or workplaces. Anyone is able to offer a silent prayer wherever he or she is at the time.” He added, “Since it has become difficult to do things you have taken for granted to this point, now is a chance to thoroughly consider what you can do yourself to console the souls of A-bomb victims.”

Reporting was carried out by the following junior writers: Atsuhito Ito, 17, Airi Shono, 17, Haruka Oikawa, 17, Yuri Furohashi, 16, Hitoha Katsura, 15, Yuna Okajima, 13, Haruka Shitanda, 16, Yuno Nakashima, 14, Aoi Miki, 15, Chihiro Yamase, 13, Jo Takeda 14, Mirei Mori, 13, Mayu Yoshida, 12, Manami Nakano, 12, and Riko Soma, 12.

(Originally published on July 27, 2020)