Junior Writers Reporting: Special report on date commemorating war’s end — Walking around Ohkunoshima Island, also known as “poison gas island”

Aug. 15, 2022

History of harming others found among island’s remnants

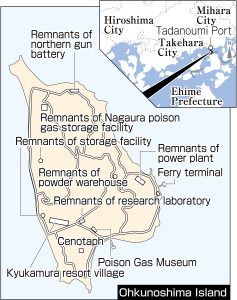

Located in the Seto Inland Sea, Ohkunoshima Island (part of Hiroshima’s Takehara City) is a popular tourist destination commonly known as “rabbit island.” The island, however, was also a “poison gas island” where the former Imperial Japanese Army once secretly manufactured poison gas. To conceal that terrible secret, the island’s very existence was kept secret, with it even being removed from World War II-era maps. Guided on this day by Masayuki Yamauchi, 77, a volunteer tour-guide, the Chugoku Shimbun’s junior writers toured the island during their summer vacation from school to report on its history. That day, August 15, marks the anniversary of the end of the war. This article will introduce readers to some of the main sites the junior writers visited.

After our roughly 90-minute express bus ride from Hiroshima Station, Mr. Yamauchi welcomed us in front of the Tadanoumi Station in Takehara City. After transiting to Tadanoumi Port, we all headed for the island by ferryboat.

On the island could be seen many tourists, who had come to visit and interact with the rabbits that are plentiful there. We first toured the Poison Gas Museum, and then walked around the remnants of storage facilities, a power plant, and other relics that convey the history of poison gas production.

Many remnants of facilities associated with the war can be found on the island. The quiet appearance of what remains made things appear as if time had eerily stopped since then, lending a firsthand sense of reality to our perceptions of events that took place in the distant past.

“We must never forget that the war not only hurt us but also caused harm to others,” said Mr. Yamauchi. He added, “It is important to learn from past history and use it in creating the future.” His words reverberated in our hearts. Ohkunoshima is a place where war can be learned about from multiple perspectives. We hope that as many people as possible can come to know that history.

Poison Gas Museum

Exhibit includes workers’ notebooks, protective suits

The Poison Gas Museum exhibits detailed explanations about the poison gas manufactured on Ohkunoshima Island, the equipment used in the production of the gas, as well as workers’ notebooks and the protective suits worn by those engaged in poison gas production.

The protective suits were made of rubber. According to Mr. Yamauchi, not all workers were provided protective suits, sometimes with one suit being shared by more than one worker. As a result, vaporized poison gas entered from worn areas or small gaps in the protective suits, leading to numerous cases of workers developing bronchitis and other illnesses. Despite the risks, those engaged in the production process were not told they were manufacturing poison gas.

And that is not all. The poison gas manufactured on Ohkunoshima Island was actually used on battlefields in China. After Japan was defeated in the war, all the poison gas manufactured and poison gas still in the manufacturing process were abandoned. Damage caused by the poison gas continues to be reported all these years after the war. Under the Chemical Weapons Convention, Japan is obligated to properly dispose of the poison gas.

Remnants of Nagaura poison gas storage facility

Island’s largest storage facility constructed by cutting through mountain

These storage facility remnants are the largest left on the island. The facility was built by cutting through a mountain and designed so as to be obscured by embankment and trees from across the sea. Therein was stored highly poisonous gas such as yperite and lewisite that caused skin damage. Housed in each of the six rooms was one tank measuring four meters in diameter and 11 meters in length. Standing in a place in which had been stored large quantities of poison gas for the purpose of taking the lives of innumerable people, we came to understand the horror of poison gas production.

Remnants of power plant

Due to conservation efforts, demolition avoided

The power plant is the place from which electric power was generated for the production of poison gas. To keep that work secret, an embankment was constructed between the power plant and the coastline to block any view from the main island. Tests were also conducted here to demonstrate whether there were any holes in the balloon bombs designed to be flown to the United States. The balloons, made by mobilized girls of school age, were said to have measured about 10 meters in diameter.

At one point, there was a plan in place to demolish the building. However, as a result of a signature-collection campaign carried out by junior high school students who had visited the island as part of a peace study project, as well as calls for preservation of the building by people who had worked at the factory in those days, the power plant still stands today.

Remnants of northern gun battery

Used as tank storage

At the end of a steep mountain path, remnants of the northern gun battery can be found. The site was used as a gun battery during the Meiji era (1868–1912) in Japanese history in case ships from overseas happened to enter the Seto Inland Sea. During World War II, it was turned into a storage facility for tanks used to deliver poison gas. This place reminds us of Japan’s wartime history and, at the same time, speaks strongly to the inhumanity of war.

Cenotaph for Ohkunoshima poison gas victims

About 1,000 people continue to suffer from aftereffects

The cenotaph for Ohkunoshima poison gas victims is a memorial to those who worked at the poison gas factory and lost their lives as a result of respiratory organ damage and other health issues. The names of 4,055 people are inscribed on the cenotaph. Every autumn, a memorial service is held under the auspices of the Ohkunoshima poison gas sufferers’ liaison council. About 6,700 people are estimated to have been engaged in poison gas production on Ohkunoshima Island, but the exact number is unclear. Even 77 years after Japan’s defeat in the war, about 1,000 people still suffer from chronic bronchitis and other illnesses.

Message from Reiko Okada, mobilized school-age girl, details how “Confidentiality is taking precedence over students’ lives”

We junior writers received a message from Reiko Okada, 92, a resident of Mihara City who had been engaged in poison gas production on Ohkunoshima Island as a mobilized student. In her message, she wrote about her wartime experiences and her hopes for peace.

A second-year student at Tadanoumi Girls’ High School (now Tadanoumi High School), Ms. Okada was engaged in varied work on Ohkunoshima Island such as production of smoke canisters, transport of poison gas cans, and manufacture of balloons for balloon bombs starting in November 1944 until Japan’s defeat in the war in August 1945.

Every job in which she engaged carried with it an element of risk. Some people suffered lung damage by inhaling dust particles to which were affixed poisonous substances. However, concealing the island’s secret took precedence over the lives of students, and even if students were injured on the job, their parents were not allowed to visit them. Ms. Okada first learned about what was contained in the canisters more than 40 years after the end of the war.

Ms. Okada was also mobilized to assist in relief efforts to aid the wounded in Hiroshima immediately after the atomic bombing. She continues to describe her experiences as someone who both suffered harm and harmed others as a result of war.

She wrote in her message about the significance of squarely facing the past and raising our “voices without hesitation and standing up in solidarity against what is wrong.” We believe that each of us must learn from the past and work to create a peaceful world.

The above article was written by the following junior reporters:

Yotsuba Sata, 17; Yuno Nakashima, 16; Shino Taguchi, 16; Riko Soma, 14; Sakura Tanura, 14; Manami Nakano, 14; Meika Kawamoto, 14; Yuko Yamashita, 13; and Gaku Kawanabe, 13.

The portion of the article on Ms. Okada was written by Hitoha Katsura, 18.

(Originally published on August 15, 2022)