The Key to a World without Nuclear Weapons: First step toward the beginning of the end of nuclear weapons

Dec. 29, 2017

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Yumi Kanazaki, and Yoshiaki Kido, Staff Writers

In 2017, inspired by the wish of the A-bomb survivors, some non-nuclear nations and segments of civil society came together to craft the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which has produced a roadmap for the abolition of nuclear weapons. The year’s Nobel Peace Prize was then awarded to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), the non-governmental organization (NGO) which made a significant contribution toward establishing the treaty. As a result, there was elation among ICAN members and supporters. At the same time, nations that continue to cling to nuclear weapons to maintain their security remain opposed to the treaty. Could 2017 be the beginning of the end of nuclear weapons? From Hiroshima, we are determined to take further steps toward a peaceful world without nuclear arms, a goal that can be reached with the guiding light of the nuclear weapons ban treaty.

Social networking sites have the power to raise awareness

“Yes, I can.” These are the words that people of various nations chanted together at a parade in Oslo, Norway to celebrate the winning of the Nobel Peace Prize by ICAN. Peace Boat, a member group of ICAN based in Tokyo, uses the hashtag “#YesICAN” when the group posts messages to social networking sites, such as Twitter, to promote a world without nuclear weapons and expand the circle of awareness involving nuclear arms among citizens with little interest in the issue.

On December 9, Momoko Miura, 18, a resident of Asakita Ward, Hiroshima and a first-year student at Hiroshima Bunkyo Women’s University, took part in a candle-lighting event in Hiroshima to celebrate ICAN’s triumph. Ms. Miura said with a smile, “Connecting peace activities with social networking is a fresh approach for me. I plan to share a photo of this event with my followers and tell them that events like these are fun.” She had little experience of peace activities before, but decided to join the event after being invited by an older schoolmate. She hopes that social networking can help encourage other young people like her, who may hesitate, to get involved in peace activities.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee described ICAN’s efforts as “ground-breaking” in its proactive use of social networking sites in order to fuel momentum for abolishing nuclear weapons. Moving forward, the group will work to strengthen public opinion for the signing and ratification of the treaty, too. In this way, the strength of civil society will be put to the test for advancing further on the road toward nuclear abolition.

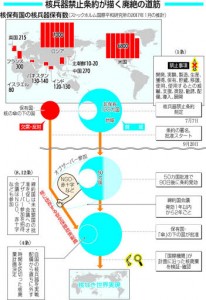

On September 20, the treaty opened for signatures by nations. ICAN is seeking for the treaty to enter into force within two years, which will require ratification by 50 nations. After this is accomplished, the focus will be on whether the state parties to the treaty and civil society can work together and compel the nuclear nations and the countries that rely on the nuclear umbrella to enter the framework of the treaty through the power of public opinion. Important actions will include holding the Meeting of State Parties, where the non-signatory nations are invited to take part as observers and NGOs can participate, and promote policies that will reduce dependence on nuclear arms, such as the “no first use” nuclear pledge and nuclear-weapon-free zones.

The Australian and Dutch members of ICAN, who spearhead the group’s activities, have been making efforts to gain the support of parliaments and corporations, from an ethics perspective, by using social networking to highlight the names and photos of politicians who are taking action to help ratify the treaty, releasing a list of “unethical” financial institutions that invest in industries related to nuclear weapons, and asking such institutions to stop doing business with nuclear weapon producers.

Still, even after ICAN was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, numerous messages expressing opposition to the nuclear weapons ban treaty have also been tweeted, on top of the nuclear peril posed by North Korea and other nuclear concerns. Such messages state opinions like: “It’s impossible to eliminate nuclear weapons” and “Banning nuclear weapons is unrealistic.” Nevertheless, “tweets of hope,” which send out a positive message to people in doubt with encouraging words like “Yes, we can,” can help strengthen momentum for nuclear abolition.

Nuclear weapons are called “ultimate evil” in Nobel Peace Prize speeches

Two members of ICAN gave speeches at the award ceremony for the Nobel Peace Prize. Their speeches took the tone of counterarguments to the criticism made by the nuclear powers and the nations under the nuclear umbrella, which have turned their backs on the nuclear weapons ban treaty. Beatrice Fihn, ICAN’s executive director, said, “These weapons are not keeping us safe.” Setsuko Thurlow, the other speaker and an A-bomb survivor, said, “These weapons are not a necessary evil; they are the ultimate evil,” and “Let this (the treaty) be the beginning of the end of nuclear weapons.”

The nuclear weapons ban treaty was established at the United Nations in July 2017. Since that time, the main criticism from the anti-treaty nations is the “security concerns” of these countries and their allies. Though the nuclear nations and their allies have argued that they also hold the goal of abolishing nuclear arms, for now they consider these nuclear arsenals a “necessary evil” for deterrence, suggesting “intolerable retaliation” (to quote Taro Kono, the Japanese foreign minister) in the event of an enemy attack.

Meanwhile, the pro-treaty nations contend that the treaty could instead strengthen security because the prohibition of nuclear weapons would help prevent the world from turning back to a nuclear arms race, and they seek to quickly realize the elimination of nuclear weapons as the only way of guaranteeing that these weapons are never used again under any circumstances. In her speech, Ms. Fihn said that possessing nuclear weapons for the purpose of deterrence only propels others, like North Korea, to join the nuclear arms race and that this creates conflict. If such conflict escalates, the risk of a nuclear attack also rises. Thus, ICAN is strongly urging all nations to join the treaty, based on the recognition that the nuclear weapons held by the nuclear nations may cause “catastrophic consequences that transcend national borders” (excerpt from the treaty’s preamble) and pose risks for the security of all human beings, including dangers that involve accidental detonation of a nuclear weapon or a nuclear attack by terrorists.

Initially, critics of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons also put forth the pessimistic view that the nations participating in this treaty might be inclined to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), the current pillar of nuclear non-proliferation efforts, but such a development has actually not taken place. At the First Committee of the U.N. General Assembly, opponents directed the brunt of their criticism at the fact that the treaty as yet has not defined any concrete measures for verifying the elimination of nuclear weapons, but proponents responded that both sides must think about this together, with the denuclearization of North Korea in mind.

Amid this opposition from the nuclear nations, the Norwegian Nobel Committee also cautioned that an international legal prohibition would not in itself eliminate a single nuclear weapon. However, former leaders of the United States and Russia, two nuclear superpowers, as well as religious leaders, have made statements which support the vision of the treaty and ICAN’s activities. Which would be safer, a world with nuclear weapons or a world without them? The treaty implicitly poses that question to us.

Japan resists taking part in the treaty

At the U.N. negotiations to establish the nuclear weapons ban treaty, how to draw the nuclear powers into the framework of the treaty, as early as possible, became a key topic of discussion. Accordingly, Article 4 of the treaty stipulates that a nuclear nation can become a signatory to the treaty even before eliminating its nuclear arsenal as long as it can meet certain conditions, such as submitting a plan designed to abolish its nuclear weapons and related facilities. Meanwhile, there are no clear-cut conditions articulated for Japan, which continues to rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, to join the treaty. Currently, the majority opinion is that Japan could take part in the treaty by forming a nuclear-free alliance with the United States.

But it is very difficult to define what sort of relationship is recognized as a non-nuclear alliance because Article 1 of the treaty prohibits state parties not only from using or threatening to use nuclear weapons but from encouraging other nations to engage in such activities. In the event of a crisis, Japan has called on the United States to use its nuclear arms. In November, when the United Nations Conference on Disarmament Issues took place in Hiroshima, there was a session about participation in the treaty but the discussion did not pursue this issue in depth.

During the session, Elayne Whyte Gómez, a panelist from Costa Rica who served as the president of the United Nations Conference to negotiate a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, explained that further research would be necessary. Mitsuru Kurosawa, a professor at Osaka Jogakuin University who specializes in international disarmament law, spoke up at the session by saying, “This is an area that wasn’t discussed thoroughly during the negotiations. At least, the United States has clearly concluded that current conditions involving Japan don’t fit within the nuclear weapons ban treaty.”

In fact, the nuclear umbrella seems to be integrated into the U.S.-Japan alliance more deeply than ever before.

Last month, it was learned that the B-52 strategic bomber, an aircraft of the U.S. Air Force that can carry nuclear weapons, and the F-15 fighter jet of the Japan Air Self-Defense Force, conducted a joint training operation to anticipate an emergency on the Korean Peninsula. During the period of the Obama administration, the Japan-U.S Extended Deterrence Dialogue was initiated and Brad Roberts, the former deputy assistant of U.S. Secretary of Defense for nuclear and missile defense policy, said that the dialogue was aimed at forming a framework of discussion similar to that of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the so-called nuclear alliance. Regarding a scenario in which nuclear weapons are used, the Japanese government has reportedly made specific requests to the United States.

Rather than the United States providing the nuclear umbrella in a one-way commitment, Japan is aggressively asking for it and deepening its involvement. It is plain that such conditions are an obstacle toward joining the treaty. Though there is a thick wall of confidentiality, it is vital that the public urge the government to take concrete action, which will require us to fundamentally review the nation’s security policy.

Commentary on the preamble of the nuclear weapons ban treaty

The preamble includes a bold description of nuclear weapons, stating: “Concerned by…the waste of economic and human resources on programmes for the production, maintenance and modernization of nuclear weapons.” In reality, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office updated the estimated budget for modernizing the U.S. nuclear arsenal over the next three decades this past October, which skyrocketed to about 1.2 trillion dollars (about 135 trillion yen).

A simple calculation shows that about 4.5 trillion yen is needed for modernization each year. This amount is roughly four times greater than the contributions (about 1.1 trillion yen) made by the U.S. government to 33 U.N. agencies last year, such as the United Nations, the United Nations Development Program, and the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF), which are working to realize 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including measures to eradicate poverty and hunger, build peace, and combat climate change. In addition, when the U.S. government puts the focus on modernizing that nation’s nuclear arsenal, talented human resources are then poured into that effort.

After such a monstrous amount of money, manpower, and materials are invested toward this end, if 100 nuclear weapons are used in a nuclear war, it is estimated that around 2 billion people will suffer from hunger due to climate changes caused by these destructive blasts.

The treaty warns that the consequences of nuclear weapons pose grave implications for the global economy and food security. Thus, the African nations that directly face the problem of poverty voted in favor of adopting the treaty. The United States Conference of Mayors also supported the treaty and passed a resolution requesting that U.S. leaders redirect the budget for modernizing nuclear arms to measures that support education and the environment.

Yasuyoshi Komizo, the secretary general of Mayors for Peace, said emphatically, “Nuclear deterrence has no power to resolve today’s various security issues.” In August, Mayors for Peace held a general assembly and adopted a new action plan. The plan defines “safe cities” as one of its two pillars, which includes countermeasures against terrorism and issues involving migrants and environmental destruction. The other pillar of the plan is the elimination of nuclear weapons.

To date, 7,514 cities from 162 nations and regions have joined Mayors for Peace with the desire to build trust among cities, address these pressing issues, and create a security framework that does not rely on nuclear deterrence, no matter the nation. Making the most of this treaty, the group will urge a change of mindset among nations that still believe that nuclear deterrence is necessary for building peace.

Effort to support and strengthen participation of women is reaffirmed

The treaty’s preamble states: “Recognizing that the equal, full and effective participation of both women and men is an essential factor for the promotion and attainment of sustainable peace and security, and committed to supporting and strengthening the effective participation of women in nuclear disarmament.” Toshiki Fujimori, 73, the assistant secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), pondered the meaning of this passage when he attended the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony in Oslo, Norway. All of the three people who presented or received the medal and certificate were women. Both the chairperson of the U.N. negotiations for the treaty and the U.N. personnel overseeing the treaty are women, too.

In 2000, the U.N. Security Council adopted the resolution on women and peace and security that seeks to involve greater participation by women in discussions on peace and security issues. This is because, despite the fact that “Civilians, particularly women and children, account for the vast majority of those adversely affected by armed conflict” (excerpt from the resolution), there is a tendency for the participation of women in such discussions to be blocked in nations where men mainly occupy positions of leadership, such as lawmakers and senior government officials.

At the talks to establish the treaty, which took place at U.N. headquarters, female diplomats from Ireland and New Zealand took the lead in the discussions. Both of these nations were ranked among the top 10 countries with the least gender gap in the global gender gap report, which was carried out by the World Economic Forum this year. The preamble of the treaty also includes a description of how exposure to radiation from the atomic bombings caused A-bomb microcephaly and other conditions in the children of women who were pregnant at that time. It reads: “Cognizant that the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons…have a disproportionate impact on women and girls, including as a result of ionizing radiation.”

Japan was ranked 114th in the gender gap report. Setsuko Thurlow, 85, the A-bomb survivor who spoke at the award ceremony, held a press conference after the ceremony and stressed that women had played a vital role in gathering signatures amid their everyday lives when the movement to ban A- and H-bombs began as a result of the incident in which crew members of a Japanese tuna fishing boat were exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1954. Speaking to Mr. Fujimori, who was seated next her at the press conference, she told him, “Let’s do this together, both men and woman.”

History of depriving indigenous people of safe lives is stressed

Nuclear tests have been conducted repeatedly more than 2,000 times around the world. One passage was added to the preamble based on a proposal made by ICAN and other groups at the treaty talks, which reads: “Recognizing the disproportionate impact of nuclear-weapon activities on indigenous peoples.” This refers to the history of the nuclear states advocating nuclear deterrence in order to maintain their own national security, forcing the indigenous peoples of former colonies to pay the price for their nuclear development activities, and depriving them of safe lives.

At the U.N. negotiations, Sue Coleman-Haseldine, 66, an Aborigine from Australia, delivered a speech. Ms. Haseldine was brought up near Maralinga, a desert area where the United Kingdom carried out nuclear tests in the 1950s and 1960s, and she was exposed to radiation from these tests in her childhood. When she shared the reality of residents in the area, who are still unable to dispel their anxiety over the effects to their health, the representatives from the U.N. nations listened to her closely.

The preamble of the treaty includes a description of compliance with international humanitarian law, and Article 6 stipulates measures for assisting victims and addressing the environmental impact of contaminated areas as a result of nuclear tests. In effect, the treaty creates the perspective of not permitting any efforts involving military development, regardless of whether or not they are related to nuclear weapons, that would violate human rights and harm the environment.

Meanwhile, anti-nuclear NGOs have spoken out strongly for the nuclear nations to take greater responsibility for these nuclear-related damages, which indigenous peoples have suffered since the process of uranium mining began, as well as accidents involving nuclear energy. Thus, at the treaty talks, ICAN called for removal of a passage in the preamble which reaffirms the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, a provision expressly granted under the NPT framework.

Some victims of nuclear testing, including Ms. Haseldine, attended the award ceremony, too. In her speech at the ceremony, Ms. Thurlow called out the names of locations used for nuclear testing, one by one, saying, “Mururoa (a French nuclear test site), Ekker (another French test site), Semipalatinsk (the former Soviet Union’s test site), Maralinga, Bikini.” To enable the nuclear sufferers to speak with one voice, it is vital that the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki strengthen their solidarity with other victims of the nuclear era.

Concluding thoughts

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Let us first read the preamble of the nuclear weapons ban treaty while trying to imagine the August 6 and August 9 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the starting point for the treaty. I recommend that this be our first step.

In particular, I would like those people who are still skeptical about the treaty to first grasp the starting point of the treaty and what would happen to human beings on the ground if just a single nuclear weapon is again used. I hope they will then take in the word “unacceptable” that the pro-treaty nations and NGOs dared to add in the preamble to stress the “sufferings of the A-bomb survivors.”

The word “unacceptable” is used not just to emphasize the sufferings of those who were forcibly exposed to radiation under the mushroom clouds of those A-bomb attacks. It is also “unacceptable” for human beings to experience such sufferings again, for any reason whatsoever, even if this would not take place within our own nation. I would like people to read these words as a resolution by humanity itself.

The treaty poses one fundamental question to the people of the nuclear powers and the nations that lie under the nuclear umbrella: Do you truly accept that, in the event of a crisis, people in an enemy nation may suffer horrific nuclear damage and that you may experience the same suffering as a result of retaliation, all as part of your nation’s security policy? This question is also asked of the citizens of the A-bombed nation, whose government continues to cling to the nuclear umbrella.

This is the last article in the series “The Key to a World without Nuclear Weapons.”

Preamble of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

The States Parties to this Treaty,

-Determined to contribute to the realization of the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations,

-Deeply concerned about the catastrophic humanitarian consequences that would result from any use of nuclear weapons, and recognizing the consequent need to completely eliminate such weapons, which remains the only way to guarantee that nuclear weapons are never used again under any circumstances,

-Mindful of the risks posed by the continued existence of nuclear weapons, including from any nuclear-weapon detonation by accident, miscalculation or design, and emphasizing that these risks concern the security of all humanity, and that all States share the responsibility to prevent any use of nuclear weapons,

-Cognizant that the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons cannot be adequately addressed, transcend national borders, pose grave implications for human survival, the environment, socioeconomic development, the global economy, food security and the health of current and future generations, and have a disproportionate impact on women and girls, including as a result of ionizing radiation,

-Acknowledging the ethical imperatives for nuclear disarmament and the urgency of achieving and maintaining a nuclear-weapon-free world, which is a global public good of the highest order, serving both national and collective security interests,

-Mindful of the unacceptable suffering of and harm caused to the victims of the use of nuclear weapons (hibakusha), as well as of those affected by the testing of nuclear weapons,

-Recognizing the disproportionate impact of nuclear-weapon activities on indigenous peoples,

-Reaffirming the need for all States at all times to comply with applicable international law, including international humanitarian law and international human rights law,

-Basing themselves on the principles and rules of international humanitarian law, in particular the principle that the right of parties to an armed conflict to choose methods or means of warfare is not unlimited, the rule of distinction, the prohibition against indiscriminate attacks, the rules on proportionality and precautions in attack, the prohibition on the use of weapons of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering, and the rules for the protection of the natural environment,

-Considering that any use of nuclear weapons would be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, in particular the principles and rules of international humanitarian law,

-Reaffirming that any use of nuclear weapons would also be abhorrent to the principles of humanity and the dictates of public conscience,

] -Recalling that, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, States must refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations, and that the establishment and maintenance of international peace and security are to be promoted with the least diversion for armaments of the world’s human and economic resources,

-Recalling also the first resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations, adopted on 24 January 1946, and subsequent resolutions which call for the elimination of nuclear weapons,

-Concerned by the slow pace of nuclear disarmament, the continued reliance on nuclear weapons in military and security concepts, doctrines and policies, and the waste of economic and human resources on programmes for the production, maintenance and modernization of nuclear weapons,

-Recognizing that a legally binding prohibition of nuclear weapons constitutes an important contribution towards the achievement and maintenance of a world free of nuclear weapons, including the irreversible, verifiable and transparent elimination of nuclear weapons, and determined to act towards that end,

-Determined to act with a view to achieving effective progress towards general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control,

-Reaffirming that there exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control,

-Reaffirming also that the full and effective implementation of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which serves as the cornerstone of the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime, has a vital role to play in promoting international peace and security,

-Recognizing the vital importance of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and its verification regime as a core element of the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime,

-Reaffirming the conviction that the establishment of the internationally recognized nuclear-weapon-free zones on the basis of arrangements freely arrived at among the States of the region concerned enhances global and regional peace and security, strengthens the nuclear non-proliferation regime and contributes towards realizing the objective of nuclear disarmament,

-Emphasizing that nothing in this Treaty shall be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of its States Parties to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination,

-Recognizing that the equal, full and effective participation of both women and men is an essential factor for the promotion and attainment of sustainable peace and security, and committed to supporting and strengthening the effective participation of women in nuclear disarmament,

-Recognizing also the importance of peace and disarmament education in all its aspects and of raising awareness of the risks and consequences of nuclear weapons for current and future generations, and committed to the dissemination of the principles and norms of this Treaty,

-Stressing the role of public conscience in the furthering of the principles of humanity as evidenced by the call for the total elimination of nuclear weapons, and recognizing the efforts to that end undertaken by the United Nations, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, other international and regional organizations, non-governmental organizations, religious leaders, parliamentarians, academics and the hibakusha.

(Originally published on December 29, 2017)

In 2017, inspired by the wish of the A-bomb survivors, some non-nuclear nations and segments of civil society came together to craft the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which has produced a roadmap for the abolition of nuclear weapons. The year’s Nobel Peace Prize was then awarded to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), the non-governmental organization (NGO) which made a significant contribution toward establishing the treaty. As a result, there was elation among ICAN members and supporters. At the same time, nations that continue to cling to nuclear weapons to maintain their security remain opposed to the treaty. Could 2017 be the beginning of the end of nuclear weapons? From Hiroshima, we are determined to take further steps toward a peaceful world without nuclear arms, a goal that can be reached with the guiding light of the nuclear weapons ban treaty.

Social networking sites have the power to raise awareness

“Yes, I can.” These are the words that people of various nations chanted together at a parade in Oslo, Norway to celebrate the winning of the Nobel Peace Prize by ICAN. Peace Boat, a member group of ICAN based in Tokyo, uses the hashtag “#YesICAN” when the group posts messages to social networking sites, such as Twitter, to promote a world without nuclear weapons and expand the circle of awareness involving nuclear arms among citizens with little interest in the issue.

On December 9, Momoko Miura, 18, a resident of Asakita Ward, Hiroshima and a first-year student at Hiroshima Bunkyo Women’s University, took part in a candle-lighting event in Hiroshima to celebrate ICAN’s triumph. Ms. Miura said with a smile, “Connecting peace activities with social networking is a fresh approach for me. I plan to share a photo of this event with my followers and tell them that events like these are fun.” She had little experience of peace activities before, but decided to join the event after being invited by an older schoolmate. She hopes that social networking can help encourage other young people like her, who may hesitate, to get involved in peace activities.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee described ICAN’s efforts as “ground-breaking” in its proactive use of social networking sites in order to fuel momentum for abolishing nuclear weapons. Moving forward, the group will work to strengthen public opinion for the signing and ratification of the treaty, too. In this way, the strength of civil society will be put to the test for advancing further on the road toward nuclear abolition.

On September 20, the treaty opened for signatures by nations. ICAN is seeking for the treaty to enter into force within two years, which will require ratification by 50 nations. After this is accomplished, the focus will be on whether the state parties to the treaty and civil society can work together and compel the nuclear nations and the countries that rely on the nuclear umbrella to enter the framework of the treaty through the power of public opinion. Important actions will include holding the Meeting of State Parties, where the non-signatory nations are invited to take part as observers and NGOs can participate, and promote policies that will reduce dependence on nuclear arms, such as the “no first use” nuclear pledge and nuclear-weapon-free zones.

The Australian and Dutch members of ICAN, who spearhead the group’s activities, have been making efforts to gain the support of parliaments and corporations, from an ethics perspective, by using social networking to highlight the names and photos of politicians who are taking action to help ratify the treaty, releasing a list of “unethical” financial institutions that invest in industries related to nuclear weapons, and asking such institutions to stop doing business with nuclear weapon producers.

Still, even after ICAN was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, numerous messages expressing opposition to the nuclear weapons ban treaty have also been tweeted, on top of the nuclear peril posed by North Korea and other nuclear concerns. Such messages state opinions like: “It’s impossible to eliminate nuclear weapons” and “Banning nuclear weapons is unrealistic.” Nevertheless, “tweets of hope,” which send out a positive message to people in doubt with encouraging words like “Yes, we can,” can help strengthen momentum for nuclear abolition.

Nuclear weapons are called “ultimate evil” in Nobel Peace Prize speeches

Two members of ICAN gave speeches at the award ceremony for the Nobel Peace Prize. Their speeches took the tone of counterarguments to the criticism made by the nuclear powers and the nations under the nuclear umbrella, which have turned their backs on the nuclear weapons ban treaty. Beatrice Fihn, ICAN’s executive director, said, “These weapons are not keeping us safe.” Setsuko Thurlow, the other speaker and an A-bomb survivor, said, “These weapons are not a necessary evil; they are the ultimate evil,” and “Let this (the treaty) be the beginning of the end of nuclear weapons.”

The nuclear weapons ban treaty was established at the United Nations in July 2017. Since that time, the main criticism from the anti-treaty nations is the “security concerns” of these countries and their allies. Though the nuclear nations and their allies have argued that they also hold the goal of abolishing nuclear arms, for now they consider these nuclear arsenals a “necessary evil” for deterrence, suggesting “intolerable retaliation” (to quote Taro Kono, the Japanese foreign minister) in the event of an enemy attack.

Meanwhile, the pro-treaty nations contend that the treaty could instead strengthen security because the prohibition of nuclear weapons would help prevent the world from turning back to a nuclear arms race, and they seek to quickly realize the elimination of nuclear weapons as the only way of guaranteeing that these weapons are never used again under any circumstances. In her speech, Ms. Fihn said that possessing nuclear weapons for the purpose of deterrence only propels others, like North Korea, to join the nuclear arms race and that this creates conflict. If such conflict escalates, the risk of a nuclear attack also rises. Thus, ICAN is strongly urging all nations to join the treaty, based on the recognition that the nuclear weapons held by the nuclear nations may cause “catastrophic consequences that transcend national borders” (excerpt from the treaty’s preamble) and pose risks for the security of all human beings, including dangers that involve accidental detonation of a nuclear weapon or a nuclear attack by terrorists.

Initially, critics of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons also put forth the pessimistic view that the nations participating in this treaty might be inclined to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), the current pillar of nuclear non-proliferation efforts, but such a development has actually not taken place. At the First Committee of the U.N. General Assembly, opponents directed the brunt of their criticism at the fact that the treaty as yet has not defined any concrete measures for verifying the elimination of nuclear weapons, but proponents responded that both sides must think about this together, with the denuclearization of North Korea in mind.

Amid this opposition from the nuclear nations, the Norwegian Nobel Committee also cautioned that an international legal prohibition would not in itself eliminate a single nuclear weapon. However, former leaders of the United States and Russia, two nuclear superpowers, as well as religious leaders, have made statements which support the vision of the treaty and ICAN’s activities. Which would be safer, a world with nuclear weapons or a world without them? The treaty implicitly poses that question to us.

Japan resists taking part in the treaty

At the U.N. negotiations to establish the nuclear weapons ban treaty, how to draw the nuclear powers into the framework of the treaty, as early as possible, became a key topic of discussion. Accordingly, Article 4 of the treaty stipulates that a nuclear nation can become a signatory to the treaty even before eliminating its nuclear arsenal as long as it can meet certain conditions, such as submitting a plan designed to abolish its nuclear weapons and related facilities. Meanwhile, there are no clear-cut conditions articulated for Japan, which continues to rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, to join the treaty. Currently, the majority opinion is that Japan could take part in the treaty by forming a nuclear-free alliance with the United States.

But it is very difficult to define what sort of relationship is recognized as a non-nuclear alliance because Article 1 of the treaty prohibits state parties not only from using or threatening to use nuclear weapons but from encouraging other nations to engage in such activities. In the event of a crisis, Japan has called on the United States to use its nuclear arms. In November, when the United Nations Conference on Disarmament Issues took place in Hiroshima, there was a session about participation in the treaty but the discussion did not pursue this issue in depth.

During the session, Elayne Whyte Gómez, a panelist from Costa Rica who served as the president of the United Nations Conference to negotiate a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, explained that further research would be necessary. Mitsuru Kurosawa, a professor at Osaka Jogakuin University who specializes in international disarmament law, spoke up at the session by saying, “This is an area that wasn’t discussed thoroughly during the negotiations. At least, the United States has clearly concluded that current conditions involving Japan don’t fit within the nuclear weapons ban treaty.”

In fact, the nuclear umbrella seems to be integrated into the U.S.-Japan alliance more deeply than ever before.

Last month, it was learned that the B-52 strategic bomber, an aircraft of the U.S. Air Force that can carry nuclear weapons, and the F-15 fighter jet of the Japan Air Self-Defense Force, conducted a joint training operation to anticipate an emergency on the Korean Peninsula. During the period of the Obama administration, the Japan-U.S Extended Deterrence Dialogue was initiated and Brad Roberts, the former deputy assistant of U.S. Secretary of Defense for nuclear and missile defense policy, said that the dialogue was aimed at forming a framework of discussion similar to that of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the so-called nuclear alliance. Regarding a scenario in which nuclear weapons are used, the Japanese government has reportedly made specific requests to the United States.

Rather than the United States providing the nuclear umbrella in a one-way commitment, Japan is aggressively asking for it and deepening its involvement. It is plain that such conditions are an obstacle toward joining the treaty. Though there is a thick wall of confidentiality, it is vital that the public urge the government to take concrete action, which will require us to fundamentally review the nation’s security policy.

Commentary on the preamble of the nuclear weapons ban treaty

The preamble includes a bold description of nuclear weapons, stating: “Concerned by…the waste of economic and human resources on programmes for the production, maintenance and modernization of nuclear weapons.” In reality, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office updated the estimated budget for modernizing the U.S. nuclear arsenal over the next three decades this past October, which skyrocketed to about 1.2 trillion dollars (about 135 trillion yen).

A simple calculation shows that about 4.5 trillion yen is needed for modernization each year. This amount is roughly four times greater than the contributions (about 1.1 trillion yen) made by the U.S. government to 33 U.N. agencies last year, such as the United Nations, the United Nations Development Program, and the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF), which are working to realize 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including measures to eradicate poverty and hunger, build peace, and combat climate change. In addition, when the U.S. government puts the focus on modernizing that nation’s nuclear arsenal, talented human resources are then poured into that effort.

After such a monstrous amount of money, manpower, and materials are invested toward this end, if 100 nuclear weapons are used in a nuclear war, it is estimated that around 2 billion people will suffer from hunger due to climate changes caused by these destructive blasts.

The treaty warns that the consequences of nuclear weapons pose grave implications for the global economy and food security. Thus, the African nations that directly face the problem of poverty voted in favor of adopting the treaty. The United States Conference of Mayors also supported the treaty and passed a resolution requesting that U.S. leaders redirect the budget for modernizing nuclear arms to measures that support education and the environment.

Yasuyoshi Komizo, the secretary general of Mayors for Peace, said emphatically, “Nuclear deterrence has no power to resolve today’s various security issues.” In August, Mayors for Peace held a general assembly and adopted a new action plan. The plan defines “safe cities” as one of its two pillars, which includes countermeasures against terrorism and issues involving migrants and environmental destruction. The other pillar of the plan is the elimination of nuclear weapons.

To date, 7,514 cities from 162 nations and regions have joined Mayors for Peace with the desire to build trust among cities, address these pressing issues, and create a security framework that does not rely on nuclear deterrence, no matter the nation. Making the most of this treaty, the group will urge a change of mindset among nations that still believe that nuclear deterrence is necessary for building peace.

Effort to support and strengthen participation of women is reaffirmed

The treaty’s preamble states: “Recognizing that the equal, full and effective participation of both women and men is an essential factor for the promotion and attainment of sustainable peace and security, and committed to supporting and strengthening the effective participation of women in nuclear disarmament.” Toshiki Fujimori, 73, the assistant secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), pondered the meaning of this passage when he attended the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony in Oslo, Norway. All of the three people who presented or received the medal and certificate were women. Both the chairperson of the U.N. negotiations for the treaty and the U.N. personnel overseeing the treaty are women, too.

In 2000, the U.N. Security Council adopted the resolution on women and peace and security that seeks to involve greater participation by women in discussions on peace and security issues. This is because, despite the fact that “Civilians, particularly women and children, account for the vast majority of those adversely affected by armed conflict” (excerpt from the resolution), there is a tendency for the participation of women in such discussions to be blocked in nations where men mainly occupy positions of leadership, such as lawmakers and senior government officials.

At the talks to establish the treaty, which took place at U.N. headquarters, female diplomats from Ireland and New Zealand took the lead in the discussions. Both of these nations were ranked among the top 10 countries with the least gender gap in the global gender gap report, which was carried out by the World Economic Forum this year. The preamble of the treaty also includes a description of how exposure to radiation from the atomic bombings caused A-bomb microcephaly and other conditions in the children of women who were pregnant at that time. It reads: “Cognizant that the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons…have a disproportionate impact on women and girls, including as a result of ionizing radiation.”

Japan was ranked 114th in the gender gap report. Setsuko Thurlow, 85, the A-bomb survivor who spoke at the award ceremony, held a press conference after the ceremony and stressed that women had played a vital role in gathering signatures amid their everyday lives when the movement to ban A- and H-bombs began as a result of the incident in which crew members of a Japanese tuna fishing boat were exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1954. Speaking to Mr. Fujimori, who was seated next her at the press conference, she told him, “Let’s do this together, both men and woman.”

History of depriving indigenous people of safe lives is stressed

Nuclear tests have been conducted repeatedly more than 2,000 times around the world. One passage was added to the preamble based on a proposal made by ICAN and other groups at the treaty talks, which reads: “Recognizing the disproportionate impact of nuclear-weapon activities on indigenous peoples.” This refers to the history of the nuclear states advocating nuclear deterrence in order to maintain their own national security, forcing the indigenous peoples of former colonies to pay the price for their nuclear development activities, and depriving them of safe lives.

At the U.N. negotiations, Sue Coleman-Haseldine, 66, an Aborigine from Australia, delivered a speech. Ms. Haseldine was brought up near Maralinga, a desert area where the United Kingdom carried out nuclear tests in the 1950s and 1960s, and she was exposed to radiation from these tests in her childhood. When she shared the reality of residents in the area, who are still unable to dispel their anxiety over the effects to their health, the representatives from the U.N. nations listened to her closely.

The preamble of the treaty includes a description of compliance with international humanitarian law, and Article 6 stipulates measures for assisting victims and addressing the environmental impact of contaminated areas as a result of nuclear tests. In effect, the treaty creates the perspective of not permitting any efforts involving military development, regardless of whether or not they are related to nuclear weapons, that would violate human rights and harm the environment.

Meanwhile, anti-nuclear NGOs have spoken out strongly for the nuclear nations to take greater responsibility for these nuclear-related damages, which indigenous peoples have suffered since the process of uranium mining began, as well as accidents involving nuclear energy. Thus, at the treaty talks, ICAN called for removal of a passage in the preamble which reaffirms the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, a provision expressly granted under the NPT framework.

Some victims of nuclear testing, including Ms. Haseldine, attended the award ceremony, too. In her speech at the ceremony, Ms. Thurlow called out the names of locations used for nuclear testing, one by one, saying, “Mururoa (a French nuclear test site), Ekker (another French test site), Semipalatinsk (the former Soviet Union’s test site), Maralinga, Bikini.” To enable the nuclear sufferers to speak with one voice, it is vital that the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki strengthen their solidarity with other victims of the nuclear era.

Concluding thoughts

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Let us first read the preamble of the nuclear weapons ban treaty while trying to imagine the August 6 and August 9 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the starting point for the treaty. I recommend that this be our first step.

In particular, I would like those people who are still skeptical about the treaty to first grasp the starting point of the treaty and what would happen to human beings on the ground if just a single nuclear weapon is again used. I hope they will then take in the word “unacceptable” that the pro-treaty nations and NGOs dared to add in the preamble to stress the “sufferings of the A-bomb survivors.”

The word “unacceptable” is used not just to emphasize the sufferings of those who were forcibly exposed to radiation under the mushroom clouds of those A-bomb attacks. It is also “unacceptable” for human beings to experience such sufferings again, for any reason whatsoever, even if this would not take place within our own nation. I would like people to read these words as a resolution by humanity itself.

The treaty poses one fundamental question to the people of the nuclear powers and the nations that lie under the nuclear umbrella: Do you truly accept that, in the event of a crisis, people in an enemy nation may suffer horrific nuclear damage and that you may experience the same suffering as a result of retaliation, all as part of your nation’s security policy? This question is also asked of the citizens of the A-bombed nation, whose government continues to cling to the nuclear umbrella.

This is the last article in the series “The Key to a World without Nuclear Weapons.”

Preamble of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

The States Parties to this Treaty,

-Determined to contribute to the realization of the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations,

-Deeply concerned about the catastrophic humanitarian consequences that would result from any use of nuclear weapons, and recognizing the consequent need to completely eliminate such weapons, which remains the only way to guarantee that nuclear weapons are never used again under any circumstances,

-Mindful of the risks posed by the continued existence of nuclear weapons, including from any nuclear-weapon detonation by accident, miscalculation or design, and emphasizing that these risks concern the security of all humanity, and that all States share the responsibility to prevent any use of nuclear weapons,

-Cognizant that the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons cannot be adequately addressed, transcend national borders, pose grave implications for human survival, the environment, socioeconomic development, the global economy, food security and the health of current and future generations, and have a disproportionate impact on women and girls, including as a result of ionizing radiation,

-Acknowledging the ethical imperatives for nuclear disarmament and the urgency of achieving and maintaining a nuclear-weapon-free world, which is a global public good of the highest order, serving both national and collective security interests,

-Mindful of the unacceptable suffering of and harm caused to the victims of the use of nuclear weapons (hibakusha), as well as of those affected by the testing of nuclear weapons,

-Recognizing the disproportionate impact of nuclear-weapon activities on indigenous peoples,

-Reaffirming the need for all States at all times to comply with applicable international law, including international humanitarian law and international human rights law,

-Basing themselves on the principles and rules of international humanitarian law, in particular the principle that the right of parties to an armed conflict to choose methods or means of warfare is not unlimited, the rule of distinction, the prohibition against indiscriminate attacks, the rules on proportionality and precautions in attack, the prohibition on the use of weapons of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering, and the rules for the protection of the natural environment,

-Considering that any use of nuclear weapons would be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, in particular the principles and rules of international humanitarian law,

-Reaffirming that any use of nuclear weapons would also be abhorrent to the principles of humanity and the dictates of public conscience,

] -Recalling that, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, States must refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations, and that the establishment and maintenance of international peace and security are to be promoted with the least diversion for armaments of the world’s human and economic resources,

-Recalling also the first resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations, adopted on 24 January 1946, and subsequent resolutions which call for the elimination of nuclear weapons,

-Concerned by the slow pace of nuclear disarmament, the continued reliance on nuclear weapons in military and security concepts, doctrines and policies, and the waste of economic and human resources on programmes for the production, maintenance and modernization of nuclear weapons,

-Recognizing that a legally binding prohibition of nuclear weapons constitutes an important contribution towards the achievement and maintenance of a world free of nuclear weapons, including the irreversible, verifiable and transparent elimination of nuclear weapons, and determined to act towards that end,

-Determined to act with a view to achieving effective progress towards general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control,

-Reaffirming that there exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control,

-Reaffirming also that the full and effective implementation of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which serves as the cornerstone of the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime, has a vital role to play in promoting international peace and security,

-Recognizing the vital importance of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and its verification regime as a core element of the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime,

-Reaffirming the conviction that the establishment of the internationally recognized nuclear-weapon-free zones on the basis of arrangements freely arrived at among the States of the region concerned enhances global and regional peace and security, strengthens the nuclear non-proliferation regime and contributes towards realizing the objective of nuclear disarmament,

-Emphasizing that nothing in this Treaty shall be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of its States Parties to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination,

-Recognizing that the equal, full and effective participation of both women and men is an essential factor for the promotion and attainment of sustainable peace and security, and committed to supporting and strengthening the effective participation of women in nuclear disarmament,

-Recognizing also the importance of peace and disarmament education in all its aspects and of raising awareness of the risks and consequences of nuclear weapons for current and future generations, and committed to the dissemination of the principles and norms of this Treaty,

-Stressing the role of public conscience in the furthering of the principles of humanity as evidenced by the call for the total elimination of nuclear weapons, and recognizing the efforts to that end undertaken by the United Nations, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, other international and regional organizations, non-governmental organizations, religious leaders, parliamentarians, academics and the hibakusha.

(Originally published on December 29, 2017)