Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Recreating cityscapes: Shima Hospital standing at hypocenter

Aug. 13, 2020

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Shima Hospital, which has become synonymous with the hypocenter, was opened in Saiku-machi, Hiroshima City (now part of Ote-machi, Naka Ward) by the late Kaoru Shima in 1933. On the morning of August 6, 1945, the hospital was devastated in the atomic bombing, which took the lives of about 80 people, including doctors, nurses and patients. The Shima family, which still operates the hospital at the same site, takes great care of pre-atomic bombing photographs that escaped the fires in their locations at the homes of hospital staff. Herein, we will trace the appearance of the hospital long ago using, among other materials, a recently discovered list of people who were at the hospital and killed in the atomic bombing. The list was written by Kaoru himself.

Medical officers with a brassard on their left arm grip military swords—this commemorative photograph was likely taken before the officers went to the front. A little boy in the lap of the late Kaoru Shima holds a small Japanese national flag in his hand. “It was taken in the inner courtyard of the hospital. The little boy is me, at around four years old,” said Kaoru’s eldest son, Kazuhide, 85, recalling distant memories. “Next to my father are my mother and my sister, who was two years younger than I.”

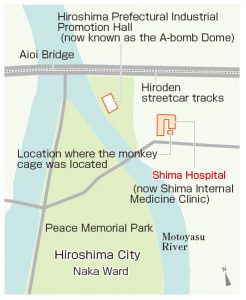

The Saiku-machi area was located on the east side of Motoyasu River. Across the river was the former Nakajima district, a bustling shopping district before the war. The area around Saiku-machi was lined with Western-style buildings, such as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now known as the A-bomb Dome) and the Hiroshima Post Office. Shima Hospital, which stood on a piece of property of about 1,300 square meters, especially captured the attention of people with its modern appearance. The hospital building was modeled on the design of an U.S. hospital.

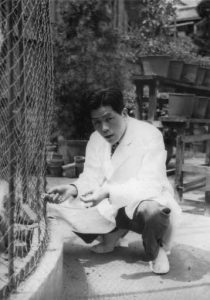

There was a cage in the inner courtyard in which five or six monkeys lived. Neighbors often came to see the animals. Kazuhide said, “I think my father wanted to entertain patients with the monkeys. They frequently got out of the cage whenever we fed them.”

“With walls more than one-meter thick, the hospital should withstand air-raids,” Kaoru used to boast of the two-story brick building. However, because of the atomic bombing, it fell into ruin, with only a mere trace left of its entrance. All doctors, nurses, and patients perished in the bombing. Their bleached bones were scattered about the site.

The list of A-bomb victims kept by the Shima family speaks to the fact that the hospital received patients from all parts of Hiroshima Prefecture, as well as people from Yamaguchi Prefecture, and those who came to Japan from the Korean Peninsula. It shows that Kaoru, who was called the “father of the Hiroshima surgical society,” was well-known for his medical skills even before the war. He never refused to treat people who were unable to pay medical expenses. They sometimes brought vegetables to him as a token of their gratitude.

On that day, August 6, he had left Hiroshima to perform an operation in the area of Kozan-cho (now part of Sera-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture). He rushed back to Saiku-machi as soon as he heard the news that Hiroshima City had been annihilated, but the heat from fires prevented him from returning to the hospital. He busily engaged in treating the wounded at Fukuromachi National School (now Fukuromachi Elementary School), which functioned as a temporary relief station, while staying at a bank that had escaped the fires. According to his memoirs, published in 1983, he walked around looking for his staff and patients. When their surviving families visited, he would tell them to take a handful of dirt home instead of bones, as it was impossible to identify exactly whose bones they were.

As a surgeon and a civil defense volunteer, Kaoru regretted not being at the hospital on that day, feeling pain as if a long nail was piercing his chest. He hardly spoke about his A-bomb experience in public. Kazuhide’s wife, Naoko, 76, said, “My father-in-law once told me, ‘A maid begged me for a vacation when August came, but I asked her to wait until the Obon Festival holidays, because we were very busy,’ as he held back his tears.” Naoko would never forget his recollection.

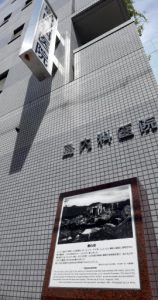

Kazuhide was safe that day, as he had been evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. Three years after the war, Kaoru rebuilt the hospital on the ruined site. When he passed away in 1977 at the age of 79, Kazuhide took over running the hospital. The hospital is now operated by Hideyuki, 49, Kaoru’s grandson and a physician. There is a board standing next to the entrance explaining that the location marks “the hypocenter.” Many people visit the location from both Japan and overseas. “Even though times and the surrounding scenery have changed, we will continue to be a clinic that provides the community with healthcare as we have been since the pre-war period,” Hideyuki emphasized.

(Originally published on July 20, 2020)

Shima Hospital, which has become synonymous with the hypocenter, was opened in Saiku-machi, Hiroshima City (now part of Ote-machi, Naka Ward) by the late Kaoru Shima in 1933. On the morning of August 6, 1945, the hospital was devastated in the atomic bombing, which took the lives of about 80 people, including doctors, nurses and patients. The Shima family, which still operates the hospital at the same site, takes great care of pre-atomic bombing photographs that escaped the fires in their locations at the homes of hospital staff. Herein, we will trace the appearance of the hospital long ago using, among other materials, a recently discovered list of people who were at the hospital and killed in the atomic bombing. The list was written by Kaoru himself.

Providing for the community even during the war

Medical officers with a brassard on their left arm grip military swords—this commemorative photograph was likely taken before the officers went to the front. A little boy in the lap of the late Kaoru Shima holds a small Japanese national flag in his hand. “It was taken in the inner courtyard of the hospital. The little boy is me, at around four years old,” said Kaoru’s eldest son, Kazuhide, 85, recalling distant memories. “Next to my father are my mother and my sister, who was two years younger than I.”

The Saiku-machi area was located on the east side of Motoyasu River. Across the river was the former Nakajima district, a bustling shopping district before the war. The area around Saiku-machi was lined with Western-style buildings, such as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now known as the A-bomb Dome) and the Hiroshima Post Office. Shima Hospital, which stood on a piece of property of about 1,300 square meters, especially captured the attention of people with its modern appearance. The hospital building was modeled on the design of an U.S. hospital.

There was a cage in the inner courtyard in which five or six monkeys lived. Neighbors often came to see the animals. Kazuhide said, “I think my father wanted to entertain patients with the monkeys. They frequently got out of the cage whenever we fed them.”

“With walls more than one-meter thick, the hospital should withstand air-raids,” Kaoru used to boast of the two-story brick building. However, because of the atomic bombing, it fell into ruin, with only a mere trace left of its entrance. All doctors, nurses, and patients perished in the bombing. Their bleached bones were scattered about the site.

The list of A-bomb victims kept by the Shima family speaks to the fact that the hospital received patients from all parts of Hiroshima Prefecture, as well as people from Yamaguchi Prefecture, and those who came to Japan from the Korean Peninsula. It shows that Kaoru, who was called the “father of the Hiroshima surgical society,” was well-known for his medical skills even before the war. He never refused to treat people who were unable to pay medical expenses. They sometimes brought vegetables to him as a token of their gratitude.

On that day, August 6, he had left Hiroshima to perform an operation in the area of Kozan-cho (now part of Sera-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture). He rushed back to Saiku-machi as soon as he heard the news that Hiroshima City had been annihilated, but the heat from fires prevented him from returning to the hospital. He busily engaged in treating the wounded at Fukuromachi National School (now Fukuromachi Elementary School), which functioned as a temporary relief station, while staying at a bank that had escaped the fires. According to his memoirs, published in 1983, he walked around looking for his staff and patients. When their surviving families visited, he would tell them to take a handful of dirt home instead of bones, as it was impossible to identify exactly whose bones they were.

As a surgeon and a civil defense volunteer, Kaoru regretted not being at the hospital on that day, feeling pain as if a long nail was piercing his chest. He hardly spoke about his A-bomb experience in public. Kazuhide’s wife, Naoko, 76, said, “My father-in-law once told me, ‘A maid begged me for a vacation when August came, but I asked her to wait until the Obon Festival holidays, because we were very busy,’ as he held back his tears.” Naoko would never forget his recollection.

Kazuhide was safe that day, as he had been evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. Three years after the war, Kaoru rebuilt the hospital on the ruined site. When he passed away in 1977 at the age of 79, Kazuhide took over running the hospital. The hospital is now operated by Hideyuki, 49, Kaoru’s grandson and a physician. There is a board standing next to the entrance explaining that the location marks “the hypocenter.” Many people visit the location from both Japan and overseas. “Even though times and the surrounding scenery have changed, we will continue to be a clinic that provides the community with healthcare as we have been since the pre-war period,” Hideyuki emphasized.

(Originally published on July 20, 2020)