Seventy-five years after the atomic bombing—Survivors’ groups at crossroads, Part 5: A-bomb museum in Hokkaido

Jul. 29, 2020

by Kyoko Niiyama, Staff Writer

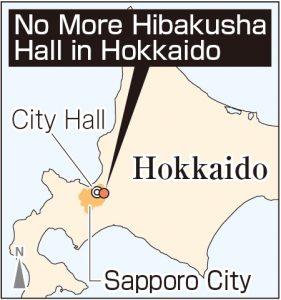

In Sapporo, a city about 1,200 kilometers from Hiroshima, A-bombed artifacts and other historical documents are displayed, including a teacup melted and deformed by the atomic bomb’s thermal rays and a piece of glass from the body of an A-bomb survivor, speaking to what happened the day of the atomic bombing. The items can be seen at the No More Hibakusha Hall in Hokkaido, built by A-bomb survivors living in Hokkaido. Similar to the A-bomb museums in the two A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the hall in Sapporo continues to convey the actual situation of the damage wrought by the atomic bombings.

The hall is operated by the Hokkaido A-bomb Survivors’ Association, based in Sapporo. It is a three-story building with a total floor space measuring about 260 square meters. The hall includes a room exhibiting about 200 items related to the atomic bombing on the second floor, with additional rooms on the third floor for survivors to share with the public their A-bombing experiences and for the storage of historical documents and materials. The association’s administrative office is on the first floor. At the top of the hall’s exterior is an artistic replica of the A-bomb Dome in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward.

Raising money to construct the hall through donation campaigns, the association opened the hall in 1991. Every year since 1965, the association has held a memorial ceremony for A-bomb victims. The idea for building a hall came up when association members indicated their wish to have a dedicated space for candid discussion, as some topics could only be approached with other survivors.

Tamotsu Sanada, 82, the association’s president and a resident of the city of Muroran in Hokkaido, said softly, “Because of this hall, survivors, second-generation survivors, and non-survivors have all been able to deepen ties with each other.”

When Mr. Sanada was seven years old, he experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima at Tenma-cho (now part of Nishi Ward), about 1.5 kilometers away from the hypocenter. He was behind a wall at the time of explosion and was thus protected from direct exposure to the bomb’s thermal rays. His cousin, however, who he was playing with at the time, suffered burns over his entire body and died a few days later. About two months after the bombing, Mr. Sanada’s family of four moved to Hokkaido with help from relatives living in the region.

Mr. Sanada is a former high school teacher. He revealed he was an A-bomb survivor to people other than his family for first time when he joined the association’s campaign for donations. Looking back that time, he said, “As I saw other A-bomb survivors working hard to build the hall, I began to have a strong sense of identity as an A-bomb survivor and wanted to be of help.”

With completion of the hall serving as an impetus, A-bomb survivors living in different places in Hokkaido joined in such activities as the sharing of A-bombing experiences with the public and A-bomb survivors’ movements. Their passion with which the activities were carried out also attracted people who were not survivors.

One such person is Kunio Kitame, 72, vice-secretary of the association who lives in Sapporo. When he was a teacher at a high school in Sapporo, he was impressed with the A-bomb survivors’ passion in continuing to share their A-bomb experiences. He invested effort into peace education activities, holding gatherings to listen to A-bomb survivors’ testimonies, and visiting the hall numerous times. After he retired from work at the school, he started to serve as an administrator of the association.

In the past, the number of A-bomb survivors living in Hokkaido exceeded 1,000. Now, 248 people are holders of an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, and 58 are members of the association. The survivors who share their A-bombing experiences with the public at the hall now number only five.

The number of visitors to the hall hovered around 1,100 annually, but last fiscal year it dropped to 929, failing to reach 1,000 for the first time. Mr. Kitame shared his concerns about the situation: “Some reasons for the smaller number are that fewer people have come to the hall to learn about the atomic bombing as preparation before going on school field trips, and the schools are spending less time on peace education.”

The association started a project in September of last year to pass on its efforts to the next generations. Working together with the Second-generation A-bomb Survivors-plus Group in Hokkaido, formed by second-generation A-bomb survivors in May 2017, the association began to create a website. Preparations are underway to release some of the contents on the internet this month—including videos of A-bomb survivors recounting their experiences or introductions of the items on display at the hall—ahead of the full launch of the website.

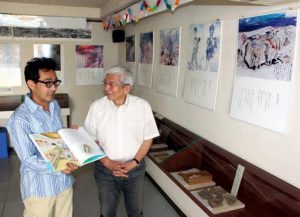

Moreover, the association published a picture book for children at the end of June. The book describes the wishes of A-bomb survivors and the history of the hall, complete with an English translation. About 2,000 copies have been printed. On July 13 and 14, the original paintings for the book were exhibited at an A-bomb exhibit held in the lobby of the Hokkaido Prefectural Offices. Tetsu Saito, 49, a member of the Second-generation A-bomb Survivors-plus Group in Hokkaido and a security guard living in Sapporo, was emphatic. “We want to introduce the book by reading it to children at the hall, after they have a chance to listen to A-bomb survivors’ testimonies.”

The association members are unable to predict definitively how long they will be able to continue activities at the hall, including the recounting of the A-bombing experiences by the survivors. But Mr. Sanada said, “This place is filled with the passion and history of A-bomb survivors in Hokkaido. Our wish to have young people take over the operations and infuse this place with their energy has only grown.” It is hoped that the hall can continue to exist as a base for people who share the wish of “No more hibakusha.”

(Originally published on July 29, 2020)

Hokkaido survivors deepen ties in conveying “No more hibakusha” message

In Sapporo, a city about 1,200 kilometers from Hiroshima, A-bombed artifacts and other historical documents are displayed, including a teacup melted and deformed by the atomic bomb’s thermal rays and a piece of glass from the body of an A-bomb survivor, speaking to what happened the day of the atomic bombing. The items can be seen at the No More Hibakusha Hall in Hokkaido, built by A-bomb survivors living in Hokkaido. Similar to the A-bomb museums in the two A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the hall in Sapporo continues to convey the actual situation of the damage wrought by the atomic bombings.

The hall is operated by the Hokkaido A-bomb Survivors’ Association, based in Sapporo. It is a three-story building with a total floor space measuring about 260 square meters. The hall includes a room exhibiting about 200 items related to the atomic bombing on the second floor, with additional rooms on the third floor for survivors to share with the public their A-bombing experiences and for the storage of historical documents and materials. The association’s administrative office is on the first floor. At the top of the hall’s exterior is an artistic replica of the A-bomb Dome in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward.

Built with donations

Raising money to construct the hall through donation campaigns, the association opened the hall in 1991. Every year since 1965, the association has held a memorial ceremony for A-bomb victims. The idea for building a hall came up when association members indicated their wish to have a dedicated space for candid discussion, as some topics could only be approached with other survivors.

Tamotsu Sanada, 82, the association’s president and a resident of the city of Muroran in Hokkaido, said softly, “Because of this hall, survivors, second-generation survivors, and non-survivors have all been able to deepen ties with each other.”

When Mr. Sanada was seven years old, he experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima at Tenma-cho (now part of Nishi Ward), about 1.5 kilometers away from the hypocenter. He was behind a wall at the time of explosion and was thus protected from direct exposure to the bomb’s thermal rays. His cousin, however, who he was playing with at the time, suffered burns over his entire body and died a few days later. About two months after the bombing, Mr. Sanada’s family of four moved to Hokkaido with help from relatives living in the region.

Mr. Sanada is a former high school teacher. He revealed he was an A-bomb survivor to people other than his family for first time when he joined the association’s campaign for donations. Looking back that time, he said, “As I saw other A-bomb survivors working hard to build the hall, I began to have a strong sense of identity as an A-bomb survivor and wanted to be of help.”

With completion of the hall serving as an impetus, A-bomb survivors living in different places in Hokkaido joined in such activities as the sharing of A-bombing experiences with the public and A-bomb survivors’ movements. Their passion with which the activities were carried out also attracted people who were not survivors.

One such person is Kunio Kitame, 72, vice-secretary of the association who lives in Sapporo. When he was a teacher at a high school in Sapporo, he was impressed with the A-bomb survivors’ passion in continuing to share their A-bomb experiences. He invested effort into peace education activities, holding gatherings to listen to A-bomb survivors’ testimonies, and visiting the hall numerous times. After he retired from work at the school, he started to serve as an administrator of the association.

Fewer than 1,000 visitors

In the past, the number of A-bomb survivors living in Hokkaido exceeded 1,000. Now, 248 people are holders of an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, and 58 are members of the association. The survivors who share their A-bombing experiences with the public at the hall now number only five.

The number of visitors to the hall hovered around 1,100 annually, but last fiscal year it dropped to 929, failing to reach 1,000 for the first time. Mr. Kitame shared his concerns about the situation: “Some reasons for the smaller number are that fewer people have come to the hall to learn about the atomic bombing as preparation before going on school field trips, and the schools are spending less time on peace education.”

The association started a project in September of last year to pass on its efforts to the next generations. Working together with the Second-generation A-bomb Survivors-plus Group in Hokkaido, formed by second-generation A-bomb survivors in May 2017, the association began to create a website. Preparations are underway to release some of the contents on the internet this month—including videos of A-bomb survivors recounting their experiences or introductions of the items on display at the hall—ahead of the full launch of the website.

Moreover, the association published a picture book for children at the end of June. The book describes the wishes of A-bomb survivors and the history of the hall, complete with an English translation. About 2,000 copies have been printed. On July 13 and 14, the original paintings for the book were exhibited at an A-bomb exhibit held in the lobby of the Hokkaido Prefectural Offices. Tetsu Saito, 49, a member of the Second-generation A-bomb Survivors-plus Group in Hokkaido and a security guard living in Sapporo, was emphatic. “We want to introduce the book by reading it to children at the hall, after they have a chance to listen to A-bomb survivors’ testimonies.”

The association members are unable to predict definitively how long they will be able to continue activities at the hall, including the recounting of the A-bombing experiences by the survivors. But Mr. Sanada said, “This place is filled with the passion and history of A-bomb survivors in Hokkaido. Our wish to have young people take over the operations and infuse this place with their energy has only grown.” It is hoped that the hall can continue to exist as a base for people who share the wish of “No more hibakusha.”

(Originally published on July 29, 2020)