Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Calling into question government’s obligations, Part 5: A-bomb Survivor’s Certificates

May 24, 2020

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

Seventy-five years ago, Masako Kan, 93, a resident of Otake City, Hiroshima Prefecture, entered Hiroshima City, destroyed in the atomic bombing, in desperate search of someone special to her. The memory remains etched in her mind. Two years ago, at the age of 91, she was finally granted an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate. “I had thought for a long time it would be impossible for me to get a certificate because the application process requires witnesses.”

Ms. Kan, who was born and raised in Kure City, met Kiyoaki Aida at her hometown workplace. Mr. Aida, three years her senior, was tall and good at baseball and the guitar. She kept to herself a growing attraction to him. After Mr. Aida quit his job, however, the two drifted apart. In around December 1944, she was surprised to receive a letter from him that indicated he had become a police officer.

Ms. Kan said, “We got along very well.” In those days, especially near the end of the war, it was difficult for young couples to date. Three months after they began corresponding, Mr. Aida asked her to marry him. However, on the night of July 1, 1945, the date she first visited and met his parents, an air raid on Kure City resulted in her house being burned down. She was forced to evacuate to her sister’s house in what is now Otake City, losing contact with Mr. Aida, who had also been affected by the air raid.

Enters city center seeking fiancé

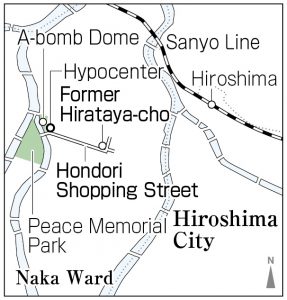

About one month after the Kure air raid, Ms. Kan received information from her friend about Mr. Aida’s whereabouts. In her desire to meet him, she visited his police box in Hirataya-cho (now part of Naka Ward, Hiroshima) on August 5. She was delighted to see him again. As they parted at a ticket gate at Hiroshima Station, Mr. Aida said, “Hiroshima has many rivers. When we meet again, let’s take a boat ride.” Ms. Kan felt a rush of excitement. Little did she know what would happen to Hiroshima the next morning.

Six days after the atomic bombing, Ms. Kan entered Hiroshima City with Mr. Aida’s mother. On the scorched ground around the Hirataya-cho police box, located about 680 meters from the hypocenter, they encountered a shoe inside of which were what looked like three partially burned toes. Mr. Aida’s mother put them in a small container, convinced that the shoe and toes were her son’s. In tears, the two returned to Kure.

After the end of World War II, Ms. Kan lost contact with Mr. Aida’s family. She did ultimately have a family with two children. Although she had obtained a form to apply for an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate, she was busy with work and raising her children and time passed without her making an application.

A few years ago, Ms. Kan shared her A-bomb experiences with Otake City officials who visited her house. At that time, she had thought it was too late to apply. Later, she was introduced to Nahoko Sato, 73, former consultant for the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hidankyo) (chaired by Sunao Tsuboi), which has continued to assist A-bomb survivors in obtaining A-bomb Survivor’s Certificates.

The certificate system classifies A-bomb survivors into several categories, including those who were in the city or designated nearby areas when the bomb was dropped and suffered direct exposure to the bomb, and those who entered a certain area within approximately two kilometers of the hypocenter within two weeks after the atomic bombing. Ms. Kan’s case belongs to the latter category of those who entered the city after the bombing. An examination to determine whether a certificate should be issued is conducted by Hiroshima City, Nagasaki City, or the prefectural governments, under contract from the national government. To apply for the certificate, the applicant is required to submit the testimonies of at least two third-party witnesses. However, as people with knowledge of the situation in those days have become elderly, it has become more and more difficult for applicants to meet the application requirements. Both Hiroshima Prefecture and Hiroshima City indicate that they use various records and materials from those times to support the applicants’ statements about their circumstances in the atomic bombing.

Some survivors unaware of certificate eligibility

Although local governments consistently respond with flexibility to applications, there are still too many barriers preventing applications from being accepted. The total number of applications made in fiscal 2019 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki prefectures and cities was 162, but only 43 were accepted. The local governments use the application documents prepared by those already in possession of the certificate as reference and criteria for acceptance. However, the central government has no policy for preserving such documents, which means they continue to be misplaced or lost in different parts of Japan.

Former consultant Ms. Sato said, “Because Ms. Kan provided the names of Mr. Aida and his mother as well as a detailed explanation of her circumstances, Hiroshima prefectural government staff were easily able to locate records.” Having an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate effectively exempts the certificate holders from payment of medical expenses and allows them to receive other benefits. For Ms. Kan, who has anemia, the certificate provides extra support.

According to Ms. Sato, many A-bomb survivors do not understand they are eligible for the certificate even though they may have entered the city shortly after the atomic bombing or visited first-aid stations. She says, “I’d like to help them obtain a certificate. I also hope that both central and local governments will provide information nationwide to encourage A-bomb survivors to apply for an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate.”

Many A-bomb survivors have suppressed memories of the atomic bombing and have not applied for a certificate for various reasons. Near the end of their lives, however, some decide to apply. As of March 31, 2019, the number of the certificate holders stood at 145,844. Both national and local governments should reach out and do their utmost for the A-bomb survivors and others not included among this number who have not yet been officially registered as victims.

(Originally published on May 24, 2020)

Finally obtained A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate at 91—“Information should be made available to encourage A-bomb survivors to apply”

Seventy-five years ago, Masako Kan, 93, a resident of Otake City, Hiroshima Prefecture, entered Hiroshima City, destroyed in the atomic bombing, in desperate search of someone special to her. The memory remains etched in her mind. Two years ago, at the age of 91, she was finally granted an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate. “I had thought for a long time it would be impossible for me to get a certificate because the application process requires witnesses.”

Ms. Kan, who was born and raised in Kure City, met Kiyoaki Aida at her hometown workplace. Mr. Aida, three years her senior, was tall and good at baseball and the guitar. She kept to herself a growing attraction to him. After Mr. Aida quit his job, however, the two drifted apart. In around December 1944, she was surprised to receive a letter from him that indicated he had become a police officer.

Ms. Kan said, “We got along very well.” In those days, especially near the end of the war, it was difficult for young couples to date. Three months after they began corresponding, Mr. Aida asked her to marry him. However, on the night of July 1, 1945, the date she first visited and met his parents, an air raid on Kure City resulted in her house being burned down. She was forced to evacuate to her sister’s house in what is now Otake City, losing contact with Mr. Aida, who had also been affected by the air raid.

Enters city center seeking fiancé

About one month after the Kure air raid, Ms. Kan received information from her friend about Mr. Aida’s whereabouts. In her desire to meet him, she visited his police box in Hirataya-cho (now part of Naka Ward, Hiroshima) on August 5. She was delighted to see him again. As they parted at a ticket gate at Hiroshima Station, Mr. Aida said, “Hiroshima has many rivers. When we meet again, let’s take a boat ride.” Ms. Kan felt a rush of excitement. Little did she know what would happen to Hiroshima the next morning.

Six days after the atomic bombing, Ms. Kan entered Hiroshima City with Mr. Aida’s mother. On the scorched ground around the Hirataya-cho police box, located about 680 meters from the hypocenter, they encountered a shoe inside of which were what looked like three partially burned toes. Mr. Aida’s mother put them in a small container, convinced that the shoe and toes were her son’s. In tears, the two returned to Kure.

After the end of World War II, Ms. Kan lost contact with Mr. Aida’s family. She did ultimately have a family with two children. Although she had obtained a form to apply for an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate, she was busy with work and raising her children and time passed without her making an application.

A few years ago, Ms. Kan shared her A-bomb experiences with Otake City officials who visited her house. At that time, she had thought it was too late to apply. Later, she was introduced to Nahoko Sato, 73, former consultant for the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hidankyo) (chaired by Sunao Tsuboi), which has continued to assist A-bomb survivors in obtaining A-bomb Survivor’s Certificates.

The certificate system classifies A-bomb survivors into several categories, including those who were in the city or designated nearby areas when the bomb was dropped and suffered direct exposure to the bomb, and those who entered a certain area within approximately two kilometers of the hypocenter within two weeks after the atomic bombing. Ms. Kan’s case belongs to the latter category of those who entered the city after the bombing. An examination to determine whether a certificate should be issued is conducted by Hiroshima City, Nagasaki City, or the prefectural governments, under contract from the national government. To apply for the certificate, the applicant is required to submit the testimonies of at least two third-party witnesses. However, as people with knowledge of the situation in those days have become elderly, it has become more and more difficult for applicants to meet the application requirements. Both Hiroshima Prefecture and Hiroshima City indicate that they use various records and materials from those times to support the applicants’ statements about their circumstances in the atomic bombing.

Some survivors unaware of certificate eligibility

Although local governments consistently respond with flexibility to applications, there are still too many barriers preventing applications from being accepted. The total number of applications made in fiscal 2019 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki prefectures and cities was 162, but only 43 were accepted. The local governments use the application documents prepared by those already in possession of the certificate as reference and criteria for acceptance. However, the central government has no policy for preserving such documents, which means they continue to be misplaced or lost in different parts of Japan.

Former consultant Ms. Sato said, “Because Ms. Kan provided the names of Mr. Aida and his mother as well as a detailed explanation of her circumstances, Hiroshima prefectural government staff were easily able to locate records.” Having an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate effectively exempts the certificate holders from payment of medical expenses and allows them to receive other benefits. For Ms. Kan, who has anemia, the certificate provides extra support.

According to Ms. Sato, many A-bomb survivors do not understand they are eligible for the certificate even though they may have entered the city shortly after the atomic bombing or visited first-aid stations. She says, “I’d like to help them obtain a certificate. I also hope that both central and local governments will provide information nationwide to encourage A-bomb survivors to apply for an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate.”

Many A-bomb survivors have suppressed memories of the atomic bombing and have not applied for a certificate for various reasons. Near the end of their lives, however, some decide to apply. As of March 31, 2019, the number of the certificate holders stood at 145,844. Both national and local governments should reach out and do their utmost for the A-bomb survivors and others not included among this number who have not yet been officially registered as victims.

(Originally published on May 24, 2020)