City plan to invite businesses and attract people to Peace Boulevard faces controversy

Oct. 13, 2020

by Hajime Niiyama, Staff Writer

Voices are being raised for and against the city government’s plan to invite cafés and other businesses and attract more people to the green belt along Peace Boulevard in Hiroshima’s downtown. Some argue that the area will be made more attractive through the development. Others say that the area, which has numerous memorial monuments to A-bomb victims and trees that survived the atomic bombing, should be maintained as a place to remember the victims. The Hiroshima City government needs to provide thorough explanations of the purpose and details of its plan.

In response to the city’s plan, a citizen’s group held an event on October 3. About 50 participants visited Peace Boulevard and learned about the history of the street and the monuments erected there. The group viewed A-bombed trees and a memorial monument to 301 students from Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School (now Minami High School), among other sights. They also toured the “Forest of Hibakusha,” where trees donated by A-bomb survivors’ groups across Japan stand.

“This area has memorial monuments and its greenery is rooted in the history of the atomic bombing. I would hope we could leave this wonderful area to future generations,” said Nozomi Otsuka, 37, a nursery school teacher living in Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward, following the event. Tetsuo Kaneko, 72, head of the Japan Congress against A- and H-Bombs, played a central role in organizing the event. As for the purpose of this event, he said, “Wouldn’t placing a priority on drawing more people into the area spoil it as a place for praying for victims? First and foremost, we want people to have an interest in learning about Peace Boulevard and the city’s plan.”

Introducing PFI

In the city’s plan, Peace Boulevard is positioned as a zone where people share their hopes for peace, while the green belt in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward will be made into a space where people get together and relax through the invitation there of cafés and other businesses. Currently, the green belt is managed as part of Hiroshima’s municipal roadways. The city is planning to designate most of the area as a park and invite shops using a system known as the Park Private Finance Initiative (PFI), which utilizes private-sector capital and knowhow. The city government will complete a master plan by the end of fiscal 2020 and start the process of selecting businesses through open recruitment in fiscal 2021.

This city government drew up the plan, as it considered it a problem that the major thoroughfare that is Peace Boulevard in the city center is not fully utilized, except during the Hiroshima Flower Festival (May 3–5) and the Hiroshima Dreamination event (November through January the following year).

The local business community has also urged the city government to more fully utilize the area. In 2016 and 2017, the Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry made a proposal to the city for enhancing the attractiveness of the street. In 2017, the business group proposed that the area be redeveloped into a “space where people can enjoy walking, relaxing and communicating with others.” In February this year, a deliberative committee composed of representatives from shopping areas, restaurants, hotels, and other industries made a proposal to the city, suggesting that the area be used as a “corridor” where people can experience peace culture and that the Park PFI be introduced.

Yoshimichi Ishimaru, 69, director-general of the Namiki-dori shopping district promotion association, is a member of the council. “This is now simply a place for people to pass through,” Mr. Ishimaru said. “To hand down those peace monuments to posterity, some move must be made to have people stay around the area.” Namiki-dori street is located near Peace Boulevard.

40 monuments and stone lanterns

During the final days of the Pacific theater of World War II, many buildings were demolished around the area that is now Peace Boulevard to prevent the spread of fires resulting from U.S. air raids. On the day of the atomic bombing, many students who were helping with such work became victims. There are now 40 cenotaphs, memorial monuments, and stone lanterns in the Naka Ward green belt alone.

Under such circumstances, A-bomb survivors’ groups and peace organizations have voiced their concerns. Toshiyuki Mimaki, 78, didn’t agree when he was asked by the city government about the plan. The acting chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo, chaired by Sunao Tsuboi), made his opinion clear. “We don’t need too much activity in a place where people pray quietly. A thorough discussion should be held about this matter.” When the city government solicited opinions in August, the other Hiroshima Hidankyo, chaired by Kunihiko Sakuma, demanded the city government withdraw its plan. “This is a place for consoling the souls of the dead where people hold annual memorial ceremonies. There are many other places bustling with people in the city. Do we need more?”

Akihito Shiiki, head of the division charged with tourism planning in the city government, said, “We want to create liveliness that people can enjoy precisely because we have peace, while at the same time sharing feelings about peace.” He stated clearly that the memorial monuments would not be moved and that the donated trees would be maintained as they are. While the Park PFI system allows up to 12 percent of a park to be used as areas for shops, according to Mr. Shiiki, the city will limit the area in the plan to two percent, among other measures. Intending to elicit understanding of the plan, Mr. Shiiki said, “We share the idea that sending out the message of peace is important.”

Peace Boulevard is a symbol of the postwar recovery of Hiroshima, which was annihilated in the atomic bombing. Introducing the Park PFI can serve as a turning point and the street transformed. The city government, however, must listen to a wide range of opinions and provide a clear vision of the direction it intends to move, instead of considering the plan’s introduction to be a foregone conclusion.

--------------------

Major developments involving Peace Boulevard

November 1951:

The street is named “Peace Boulevard” after the public was invited to submit entries for name ideas.

February 1957:

City government calls widely for donation of trees to create a green belt.

May 1965:

The entire roughly 3.8 kilometers of Peace Boulevard is opened.

November 2002:

Hiroshima Dreamination, based on a fairyland theme, begins.

September 2004:

The Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry makes a proposal to the city about revitalization of the city center, including Peace Boulevard.

October 2016:

The Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry makes a proposal to the city about increasing the appeal of Peace Boulevard.

November 2016:

A group for deliberation about how to make Peace Boulevard a more active area and composed of members from private and public sectors, including the Hiroshima City government, launches its three-year activities. The group starts creation of plans for outdoor cafés and art exhibits.

October 2017:

The Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry makes a proposal to the city for further enhancing the appeal of Peace Boulevard.

February 2019:

Responding to a question during a city council meeting, Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui announces that the city is considering introduction of the Park FPI system to Peace Boulevard.

February 2020:

A proposal is made by a group of people from nearby shopping areas working toward making Peace Boulevard a more active area. The group suggests that the city introduce businesses to enhance the area’s liveliness by introducing the Park PFI.

July 2020:

The city government begins to solicit opinions on introducing the Park PFI to attract more people to the area.

August 2020:

The Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations chaired by Kunihiko Sakuma demands that the city government withdraw its plan for attracting more people to Peace Boulevard.

--------------------

Park PFI and plan to make Peace Boulevard busier

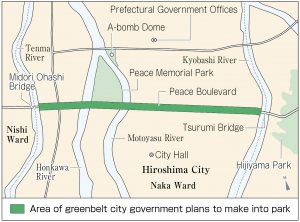

The Park Private Finance Initiative, or Park PFI, is a system through which private businesses selected through application open facilities as cafés and shops in urban park areas and return part of their profits to improving the parks including the greenery. The system was established under the revised 2017 Urban Park Act. Hiroshima’s Peace Boulevard, including the green belt, is currently regarded as part of the municipal roadway system, and restaurants are unable to operate there on a continuous basis. The city government’s idea is to make a park out of most of the 5.7-hectare green belt stretching about 2.5 kilometers between Midori Bridge and Tsurumi Bridge in Naka Ward. The plan also calls for the establishment of for-profit organizations in the park. The city government has not decided on the number of shops or the area they are to occupy. There are 1,041 trees currently in the green belt, 275 of which are believed to have been donated during the campaign held by the city government in the 1950s.

(Originally published on October 13, 2020)

Pros: Will enhance attractiveness of area

Cons: Area should be used as place to console victims

Voices are being raised for and against the city government’s plan to invite cafés and other businesses and attract more people to the green belt along Peace Boulevard in Hiroshima’s downtown. Some argue that the area will be made more attractive through the development. Others say that the area, which has numerous memorial monuments to A-bomb victims and trees that survived the atomic bombing, should be maintained as a place to remember the victims. The Hiroshima City government needs to provide thorough explanations of the purpose and details of its plan.

In response to the city’s plan, a citizen’s group held an event on October 3. About 50 participants visited Peace Boulevard and learned about the history of the street and the monuments erected there. The group viewed A-bombed trees and a memorial monument to 301 students from Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School (now Minami High School), among other sights. They also toured the “Forest of Hibakusha,” where trees donated by A-bomb survivors’ groups across Japan stand.

“This area has memorial monuments and its greenery is rooted in the history of the atomic bombing. I would hope we could leave this wonderful area to future generations,” said Nozomi Otsuka, 37, a nursery school teacher living in Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward, following the event. Tetsuo Kaneko, 72, head of the Japan Congress against A- and H-Bombs, played a central role in organizing the event. As for the purpose of this event, he said, “Wouldn’t placing a priority on drawing more people into the area spoil it as a place for praying for victims? First and foremost, we want people to have an interest in learning about Peace Boulevard and the city’s plan.”

Introducing PFI

In the city’s plan, Peace Boulevard is positioned as a zone where people share their hopes for peace, while the green belt in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward will be made into a space where people get together and relax through the invitation there of cafés and other businesses. Currently, the green belt is managed as part of Hiroshima’s municipal roadways. The city is planning to designate most of the area as a park and invite shops using a system known as the Park Private Finance Initiative (PFI), which utilizes private-sector capital and knowhow. The city government will complete a master plan by the end of fiscal 2020 and start the process of selecting businesses through open recruitment in fiscal 2021.

This city government drew up the plan, as it considered it a problem that the major thoroughfare that is Peace Boulevard in the city center is not fully utilized, except during the Hiroshima Flower Festival (May 3–5) and the Hiroshima Dreamination event (November through January the following year).

The local business community has also urged the city government to more fully utilize the area. In 2016 and 2017, the Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry made a proposal to the city for enhancing the attractiveness of the street. In 2017, the business group proposed that the area be redeveloped into a “space where people can enjoy walking, relaxing and communicating with others.” In February this year, a deliberative committee composed of representatives from shopping areas, restaurants, hotels, and other industries made a proposal to the city, suggesting that the area be used as a “corridor” where people can experience peace culture and that the Park PFI be introduced.

Yoshimichi Ishimaru, 69, director-general of the Namiki-dori shopping district promotion association, is a member of the council. “This is now simply a place for people to pass through,” Mr. Ishimaru said. “To hand down those peace monuments to posterity, some move must be made to have people stay around the area.” Namiki-dori street is located near Peace Boulevard.

40 monuments and stone lanterns

During the final days of the Pacific theater of World War II, many buildings were demolished around the area that is now Peace Boulevard to prevent the spread of fires resulting from U.S. air raids. On the day of the atomic bombing, many students who were helping with such work became victims. There are now 40 cenotaphs, memorial monuments, and stone lanterns in the Naka Ward green belt alone.

Under such circumstances, A-bomb survivors’ groups and peace organizations have voiced their concerns. Toshiyuki Mimaki, 78, didn’t agree when he was asked by the city government about the plan. The acting chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo, chaired by Sunao Tsuboi), made his opinion clear. “We don’t need too much activity in a place where people pray quietly. A thorough discussion should be held about this matter.” When the city government solicited opinions in August, the other Hiroshima Hidankyo, chaired by Kunihiko Sakuma, demanded the city government withdraw its plan. “This is a place for consoling the souls of the dead where people hold annual memorial ceremonies. There are many other places bustling with people in the city. Do we need more?”

Akihito Shiiki, head of the division charged with tourism planning in the city government, said, “We want to create liveliness that people can enjoy precisely because we have peace, while at the same time sharing feelings about peace.” He stated clearly that the memorial monuments would not be moved and that the donated trees would be maintained as they are. While the Park PFI system allows up to 12 percent of a park to be used as areas for shops, according to Mr. Shiiki, the city will limit the area in the plan to two percent, among other measures. Intending to elicit understanding of the plan, Mr. Shiiki said, “We share the idea that sending out the message of peace is important.”

Peace Boulevard is a symbol of the postwar recovery of Hiroshima, which was annihilated in the atomic bombing. Introducing the Park PFI can serve as a turning point and the street transformed. The city government, however, must listen to a wide range of opinions and provide a clear vision of the direction it intends to move, instead of considering the plan’s introduction to be a foregone conclusion.

--------------------

Major developments involving Peace Boulevard

November 1951:

The street is named “Peace Boulevard” after the public was invited to submit entries for name ideas.

February 1957:

City government calls widely for donation of trees to create a green belt.

May 1965:

The entire roughly 3.8 kilometers of Peace Boulevard is opened.

November 2002:

Hiroshima Dreamination, based on a fairyland theme, begins.

September 2004:

The Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry makes a proposal to the city about revitalization of the city center, including Peace Boulevard.

October 2016:

The Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry makes a proposal to the city about increasing the appeal of Peace Boulevard.

November 2016:

A group for deliberation about how to make Peace Boulevard a more active area and composed of members from private and public sectors, including the Hiroshima City government, launches its three-year activities. The group starts creation of plans for outdoor cafés and art exhibits.

October 2017:

The Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry makes a proposal to the city for further enhancing the appeal of Peace Boulevard.

February 2019:

Responding to a question during a city council meeting, Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui announces that the city is considering introduction of the Park FPI system to Peace Boulevard.

February 2020:

A proposal is made by a group of people from nearby shopping areas working toward making Peace Boulevard a more active area. The group suggests that the city introduce businesses to enhance the area’s liveliness by introducing the Park PFI.

July 2020:

The city government begins to solicit opinions on introducing the Park PFI to attract more people to the area.

August 2020:

The Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations chaired by Kunihiko Sakuma demands that the city government withdraw its plan for attracting more people to Peace Boulevard.

--------------------

Keywords

Park PFI and plan to make Peace Boulevard busier

The Park Private Finance Initiative, or Park PFI, is a system through which private businesses selected through application open facilities as cafés and shops in urban park areas and return part of their profits to improving the parks including the greenery. The system was established under the revised 2017 Urban Park Act. Hiroshima’s Peace Boulevard, including the green belt, is currently regarded as part of the municipal roadway system, and restaurants are unable to operate there on a continuous basis. The city government’s idea is to make a park out of most of the 5.7-hectare green belt stretching about 2.5 kilometers between Midori Bridge and Tsurumi Bridge in Naka Ward. The plan also calls for the establishment of for-profit organizations in the park. The city government has not decided on the number of shops or the area they are to occupy. There are 1,041 trees currently in the green belt, 275 of which are believed to have been donated during the campaign held by the city government in the 1950s.

(Originally published on October 13, 2020)