Seventy-five years after the atomic bombing—Survivors’ groups at crossroads, Part 7: From Hiroshima to the world

Jul. 31, 2020

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

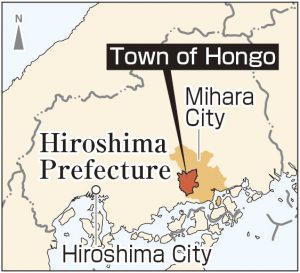

“It’s unbelievable,” said Sumiko Nakamura, 86, president of the A-bomb survivors’ group in the town of Hongo, Mihara City, as she raised her voice in anger at a remark made by U.S. President Donald Trump on July 16. He had praised the first nuclear test in history carried out by his country as a “remarkable feat.” The test in July 1945 led to the catastrophes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the following month. “Those who actually experienced the damage caused by the atomic bombings have to raise their voices,” emphasized Ms. Nakamura, whose health is now poor.

Delegation of A-bomb survivors sent to conferences

Since the era of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, A-bomb survivors have consistently made an appeal—by sharing their A-bomb accounts in various parts of the world—that “no one else should have to face the same kind of suffering.” The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) has sent numerous delegations to conferences, including the first United Nations Special Session on Disarmament, held in 1978. Since 2005, the group has sent a delegation to the Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which is held in New York City every five years.

Ms. Nakamura joined the 2005, 2010, and 2015 delegations. She first started speaking about her A-bombing experiences when she was more than 50 years of age, after losing her husband in an accident and struggling to raise their three children. She then also obtained an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and became involved in the organization’s activities. It was at that point she could finally reflect on what she had gone through.

She experienced the atomic bombing when she was in the sixth grade at Tomo National School (now Tomo Elementary School, in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward). She was exposed to “a pitch-black rain shower” on her way back home from school. A few hours later, she saw numerous wounded people escaping from the city. “They were hideously burned and looked as if they were about to fall apart at any moment,” she said.

The next day, Ms. Nakamura and her father went into the city of Hiroshima looking for relatives. Dead bodies filling the riverbanks were bundled into the back of trucks like so many logs. The strong stench of dead bodies remains etched in her memory. “Many documents and photographs related to the atomic bombing exist, but nothing can convey that smell,” she recounted, wincing.

Ms. Nakamura joined the 2005 delegation to the United Nations and there shared her account to an overseas audience for the first time. Until then, she mainly spoke locally in Japan.

Although not a polished public speaker, she spoke with passion at a high school in New York City. When she finished, students rushed up to her to say, “We learned about the atomic bombings at school, but we didn’t know what really happened. We respect you for coming all the way to the United States and sharing your experience with us.” She was pleased to learn that her words resonated with the students and affirmed her feeling that it was her mission to inform the world of the consequences of the atomic bombing.

Joined demonstration in New York City

After returning from the United States, she suffered from a stroke and cervical cancer. With her “mission” in mind, she continued rehabilitation and realized her wish by traveling to the United States in 2010 and 2015. She repeatedly talked about her A-bombing experience and participated in a demonstration to make an appeal to the American people.

Backed by growing attention to the idea of the “inhumane nature” of nuclear weapons, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted in July 2017 at a United Nations conference. The preamble of the weapons ban treaty, signed by 122 national and regions, states that “…mindful of the unacceptable suffering of and harm caused to the victims of the use of nuclear weapons (hibakusha).” Ms. Nakamura reservedly rejoiced over the treaty. “It is a milestone achieved by A-bomb survivors who had been making steady efforts even before I joined the movement.”

The treaty needs to be ratified by 50 countries and regions for the treaty to enter into effect. Currently, 40 countries and regions have done so, with 10 nations still to go. However, she is concerned about the attitude of the Japanese government, which relies on the U.S. “nuclear umbrella” and continues to turn its back on the treaty. They have shown no sign of putting the brakes on the United States’ move to strengthen its nuclear-arms policy, including the deployment of low-yield nuclear weapons for active use.

“Because it is the country that experienced the atomic bombings, Japan should have become the first to ratify the treaty and lead the international community into putting the treaty into effect,” Ms. Nakamura said. She resigned herself to not traveling to the United States in April and May this year for the NPT Review Conference, as she requires medical equipment such as an oxygen cylinder to get by. The conference was postponed due to COVID-19 outbreak and a new schedule has, as yet, not been confirmed.

The organization Ms. Nakamura belongs to does not have a successor to take over leadership of the group and it is unclear whether it can continue its activities into the future. “It’s getting harder for A-bomb survivors to move around. If Japan is to bill itself as ‘the only nation that has experienced the atomic bombings,’ the country should make appeals to the world for the abolition of nuclear weapons.” Ms. Nakamura sincerely hopes that the government acts for the sake of the A-bomb survivors.

(Originally published on July 31, 2020)

A-bomb survivors expect Japanese government to continue conveying message

“It’s unbelievable,” said Sumiko Nakamura, 86, president of the A-bomb survivors’ group in the town of Hongo, Mihara City, as she raised her voice in anger at a remark made by U.S. President Donald Trump on July 16. He had praised the first nuclear test in history carried out by his country as a “remarkable feat.” The test in July 1945 led to the catastrophes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the following month. “Those who actually experienced the damage caused by the atomic bombings have to raise their voices,” emphasized Ms. Nakamura, whose health is now poor.

Delegation of A-bomb survivors sent to conferences

Since the era of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, A-bomb survivors have consistently made an appeal—by sharing their A-bomb accounts in various parts of the world—that “no one else should have to face the same kind of suffering.” The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) has sent numerous delegations to conferences, including the first United Nations Special Session on Disarmament, held in 1978. Since 2005, the group has sent a delegation to the Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which is held in New York City every five years.

Ms. Nakamura joined the 2005, 2010, and 2015 delegations. She first started speaking about her A-bombing experiences when she was more than 50 years of age, after losing her husband in an accident and struggling to raise their three children. She then also obtained an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and became involved in the organization’s activities. It was at that point she could finally reflect on what she had gone through.

She experienced the atomic bombing when she was in the sixth grade at Tomo National School (now Tomo Elementary School, in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward). She was exposed to “a pitch-black rain shower” on her way back home from school. A few hours later, she saw numerous wounded people escaping from the city. “They were hideously burned and looked as if they were about to fall apart at any moment,” she said.

The next day, Ms. Nakamura and her father went into the city of Hiroshima looking for relatives. Dead bodies filling the riverbanks were bundled into the back of trucks like so many logs. The strong stench of dead bodies remains etched in her memory. “Many documents and photographs related to the atomic bombing exist, but nothing can convey that smell,” she recounted, wincing.

Ms. Nakamura joined the 2005 delegation to the United Nations and there shared her account to an overseas audience for the first time. Until then, she mainly spoke locally in Japan.

Although not a polished public speaker, she spoke with passion at a high school in New York City. When she finished, students rushed up to her to say, “We learned about the atomic bombings at school, but we didn’t know what really happened. We respect you for coming all the way to the United States and sharing your experience with us.” She was pleased to learn that her words resonated with the students and affirmed her feeling that it was her mission to inform the world of the consequences of the atomic bombing.

Joined demonstration in New York City

After returning from the United States, she suffered from a stroke and cervical cancer. With her “mission” in mind, she continued rehabilitation and realized her wish by traveling to the United States in 2010 and 2015. She repeatedly talked about her A-bombing experience and participated in a demonstration to make an appeal to the American people.

Backed by growing attention to the idea of the “inhumane nature” of nuclear weapons, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted in July 2017 at a United Nations conference. The preamble of the weapons ban treaty, signed by 122 national and regions, states that “…mindful of the unacceptable suffering of and harm caused to the victims of the use of nuclear weapons (hibakusha).” Ms. Nakamura reservedly rejoiced over the treaty. “It is a milestone achieved by A-bomb survivors who had been making steady efforts even before I joined the movement.”

The treaty needs to be ratified by 50 countries and regions for the treaty to enter into effect. Currently, 40 countries and regions have done so, with 10 nations still to go. However, she is concerned about the attitude of the Japanese government, which relies on the U.S. “nuclear umbrella” and continues to turn its back on the treaty. They have shown no sign of putting the brakes on the United States’ move to strengthen its nuclear-arms policy, including the deployment of low-yield nuclear weapons for active use.

“Because it is the country that experienced the atomic bombings, Japan should have become the first to ratify the treaty and lead the international community into putting the treaty into effect,” Ms. Nakamura said. She resigned herself to not traveling to the United States in April and May this year for the NPT Review Conference, as she requires medical equipment such as an oxygen cylinder to get by. The conference was postponed due to COVID-19 outbreak and a new schedule has, as yet, not been confirmed.

The organization Ms. Nakamura belongs to does not have a successor to take over leadership of the group and it is unclear whether it can continue its activities into the future. “It’s getting harder for A-bomb survivors to move around. If Japan is to bill itself as ‘the only nation that has experienced the atomic bombings,’ the country should make appeals to the world for the abolition of nuclear weapons.” Ms. Nakamura sincerely hopes that the government acts for the sake of the A-bomb survivors.

(Originally published on July 31, 2020)