Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Dispersed materials, hindered research

Apr. 6, 2020

by Yuji Yamamoto and Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writers

To grasp an overall picture of the damage wrought by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is essential to collect, preserve, and utilize various materials in different forms, such as notes written by survivors, records left by doctors, and photographs. Such materials as pathology specimens of organs, however, were confiscated and stored by the U.S. military after World War II. Efforts continue to “fill voids” that remain by retrieving such materials from the United States and other countries. Another urgent task is to prevent the materials from deteriorating and protect them from any risk of being dispersed and discarded. This article will look into possible measures to protect such “wandering” materials and link them together to come up with a comprehensive picture of the reality of the atomic bombings.

“DIED 12 August 1945,” reads an autopsy report of a 13-year-old girl on display among other documents written in English at the Institute of the History of Medicine in the School of Medicine at Hiroshima University, located in the city’s Minami Ward. The girl was 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing and died six days later. According to the report, her “hypoplasia of bone marrow” was considered to have been the result of exposure to A-bomb radiation.

The girl’s autopsy was performed by a medical officer of the former Imperial Japanese Army. The data the officer compiled were submitted to the U.S. military and translated into English. The document, part of the “materials returned by the U.S. military,” was returned to the A-bombed cities in 1973 by the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

About 11,000 materials concerning Hiroshima have been returned. They include documents recording burns and acute symptoms, organ specimens preserved in formalin, specimens embedded in paraffin blocks, and samples fixed on glass slides. The materials are stored at Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM).

“I thought to myself that some pretty incredible items had come back. I knew at a glance they were in good condition. I felt responsible for preserving them,” said Kaichi Fukasawa, 93, describing how he was surprised when he opened the wooden boxes returned by the United States. At that time, Mr. Fukasawa, a pathologist and current resident of Higashihiroshima, was the director of RIRBM’s specimen center.

Akin to spoils of war

After the atomic bombings and Japan’s unconditional surrender, the Joint Commission, a joint Japan-U.S. survey team, entered Hiroshima and began full-scale work in October 1945. Despite the collaborative nature implied by the name, the group’s surveys were carried out under the occupation of Japan and led by the U.S. military. The joint team took over a huge amount of materials collected by researchers from Japanese universities and military doctors. Records on victims collected shortly after the atomic bombing were perfect for the U.S. military to measure the lethality of such weapons.

The late Shigeyasu Amano was a pathologist and a member of the survey team from Kyoto University. The confiscation of the materials was compulsory and “unacceptably disagreeable,” he wrote. “Although we had a hard time with blood and tissue samples from autopsies for medical purposes, they were treated like spoils of war,” he wrote in his memoir Genbaku Igaku Shimatsu (Atomic Bomb Medical Outcomes).

Under the control of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces, Japanese scientists were not allowed to freely investigate the damage caused by the atomic bombing or make their findings public. Meanwhile, the U.S. military used to their advantage the “spoils of war” exchanged for the lives of A-bomb victims. The United States enhanced its nuclear arsenal during the Cold War while, at the same time, it conducted research to prepare for possible nuclear war with the Soviet Union, from which U.S. citizens could be exposed to radiation.

The materials were returned in 1973 after the issue was discussed in Japan’s National Diet, which led to negotiations between the two governments. In Hiroshima, the Atomic Bomb White Paper Movement, which called for clarification of the overall damage wrought by the atomic bombing, turned into a groundswell, building momentum for the collection of A-bomb materials.

Among those items returned from the U.S. military were photos of the devastated city taken by Japanese. When they were put on display in Hiroshima in 1973, the exhibit venue was packed with people. Some visitors indicated they were the subject in one or another of the photographs and told their experiences of the atomic bombing. The “spoils of war” returned to Hiroshima after 30 years became “witnesses” communicating the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons without having to speak a word.

Key to shedding light on damage

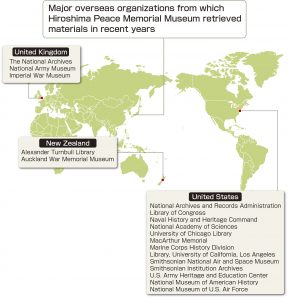

About a half-century later, some of the materials are still stored in countries overseas. Between fiscal 2013 and 2019, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in Naka Ward, sent its staff to the United States, as well as the United Kingdom and New Zealand, which made up the occupation forces. The staff visited museums and other facilities and collected a total of 7,000 items, many of which were photos taken of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing.

One photo shows an emergency relief station at Honkawa National School, which was close to the hypocenter. The photo is believed to have been taken in August 1945, by the late Toshio Kawamoto, a member of the Hiroshima Prefectural Police Department’s photography team. The photo is one that the Peace Memorial Museum did not have. Aerial photos taken by the U.S. military show the fire-devastated city from different angles and altitudes. By comparing and analyzing the images, new information on the damage can be obtained.

“These photos were taken to understand the effects of the bombing from a military point of view, but we would like to position them as materials to understand the horrors of the atomic bombing,” said Ryo Koyama, 39, a curator at the museum. There will be no end to efforts made at retrieving materials that can be used to fill “the voids.”

--------------------

If the materials were to be collected systematically and passed down to future generations, new facts could be brought to light. Some new discoveries should be possible as technology advances. “Preservation” of the materials in and of itself is equivalent to unceasing efforts to learn lessons from the past. Nevertheless, some photos and documents are on the verge of being scattered and lost. Pathological specimens are deteriorating over time. What is the status of those materials in Hiroshima?

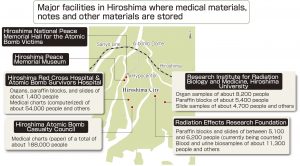

Medical materials include medical charts based on examinations of survivors, organ and tissue specimens and findings, as well as such biosamples as blood and urine. In Hiroshima, Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, located in Minami Ward, and three other facilities store most of such materials.

A-bomb survivors must live their entire lives carrying the burden of potential effects from A-bomb radiation on their health. The amount of related materials is huge. All the facilities have been struggling to secure space for storing the ever-increasing volume. Digitization of medical charts is underway to ensure that the materials are preserved and utilized. As some medical charts are stored at other facilities, some argue that it is necessary to grasp the present situation and set up measures to preserve them.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in Naka Ward, has been collecting photos of the terrible sights after the atomic bombing as well as personal belongings of victims. Such materials can be seen in the museum’s database on its website. Photos of Hiroshima’s cityscapes before the bombing are also kept at the Hiroshima Municipal Archives and the Hiroshima Central Municipal Library.

Information about the reality of the atomic bombing includes accounts written by survivors and victims’ family members. The Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, which is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, has been collecting such written information. On the other hand, public documents on relief measures for survivors and those on activities of survivor groups are on the verge of being scattered or discarded, as such groups are dissolving because of the advanced ages of survivors. People are also calling for adequate facilities for preserving materials related to literary works on the atomic bombing written while press censorship was being eluded during the occupation.

A great variety of large quantities of materials are stored in different locations. How can they be utilized? In 1971, the Science Council of Japan advised the national government that it was a pressing need for Japan to create atomic and hydrogen bomb victim materials centers in Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Tokyo. This advice matched the awareness of the problem held by scientists in the A-bombed cities. The only measure adopted, however, was expansion of the existing facilities at Hiroshima University. The task of the A-bombed nation of Japan, which systematically collects, organizes, and stores such materials, remains unfinished.

Materials related to Hiroshima returned from the U.S. in 1973

・Medical record holders of 9,060 people

・Organ samples preserved in formalin of 35 people

・Paraffin blocks of 284 people

・Slides of 669 people

・1,205 photographs (film)

※According to a 1973 report by the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine at Hiroshima University

(Originally published on April 6, 2020)

To grasp an overall picture of the damage wrought by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is essential to collect, preserve, and utilize various materials in different forms, such as notes written by survivors, records left by doctors, and photographs. Such materials as pathology specimens of organs, however, were confiscated and stored by the U.S. military after World War II. Efforts continue to “fill voids” that remain by retrieving such materials from the United States and other countries. Another urgent task is to prevent the materials from deteriorating and protect them from any risk of being dispersed and discarded. This article will look into possible measures to protect such “wandering” materials and link them together to come up with a comprehensive picture of the reality of the atomic bombings.

Huge amount of materials taken to U.S. during occupation of Japan

Efforts ongoing to return them to A-bombed cities

“DIED 12 August 1945,” reads an autopsy report of a 13-year-old girl on display among other documents written in English at the Institute of the History of Medicine in the School of Medicine at Hiroshima University, located in the city’s Minami Ward. The girl was 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing and died six days later. According to the report, her “hypoplasia of bone marrow” was considered to have been the result of exposure to A-bomb radiation.

The girl’s autopsy was performed by a medical officer of the former Imperial Japanese Army. The data the officer compiled were submitted to the U.S. military and translated into English. The document, part of the “materials returned by the U.S. military,” was returned to the A-bombed cities in 1973 by the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

About 11,000 materials concerning Hiroshima have been returned. They include documents recording burns and acute symptoms, organ specimens preserved in formalin, specimens embedded in paraffin blocks, and samples fixed on glass slides. The materials are stored at Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM).

“I thought to myself that some pretty incredible items had come back. I knew at a glance they were in good condition. I felt responsible for preserving them,” said Kaichi Fukasawa, 93, describing how he was surprised when he opened the wooden boxes returned by the United States. At that time, Mr. Fukasawa, a pathologist and current resident of Higashihiroshima, was the director of RIRBM’s specimen center.

Akin to spoils of war

After the atomic bombings and Japan’s unconditional surrender, the Joint Commission, a joint Japan-U.S. survey team, entered Hiroshima and began full-scale work in October 1945. Despite the collaborative nature implied by the name, the group’s surveys were carried out under the occupation of Japan and led by the U.S. military. The joint team took over a huge amount of materials collected by researchers from Japanese universities and military doctors. Records on victims collected shortly after the atomic bombing were perfect for the U.S. military to measure the lethality of such weapons.

The late Shigeyasu Amano was a pathologist and a member of the survey team from Kyoto University. The confiscation of the materials was compulsory and “unacceptably disagreeable,” he wrote. “Although we had a hard time with blood and tissue samples from autopsies for medical purposes, they were treated like spoils of war,” he wrote in his memoir Genbaku Igaku Shimatsu (Atomic Bomb Medical Outcomes).

Under the control of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces, Japanese scientists were not allowed to freely investigate the damage caused by the atomic bombing or make their findings public. Meanwhile, the U.S. military used to their advantage the “spoils of war” exchanged for the lives of A-bomb victims. The United States enhanced its nuclear arsenal during the Cold War while, at the same time, it conducted research to prepare for possible nuclear war with the Soviet Union, from which U.S. citizens could be exposed to radiation.

The materials were returned in 1973 after the issue was discussed in Japan’s National Diet, which led to negotiations between the two governments. In Hiroshima, the Atomic Bomb White Paper Movement, which called for clarification of the overall damage wrought by the atomic bombing, turned into a groundswell, building momentum for the collection of A-bomb materials.

Among those items returned from the U.S. military were photos of the devastated city taken by Japanese. When they were put on display in Hiroshima in 1973, the exhibit venue was packed with people. Some visitors indicated they were the subject in one or another of the photographs and told their experiences of the atomic bombing. The “spoils of war” returned to Hiroshima after 30 years became “witnesses” communicating the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons without having to speak a word.

Key to shedding light on damage

About a half-century later, some of the materials are still stored in countries overseas. Between fiscal 2013 and 2019, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in Naka Ward, sent its staff to the United States, as well as the United Kingdom and New Zealand, which made up the occupation forces. The staff visited museums and other facilities and collected a total of 7,000 items, many of which were photos taken of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing.

One photo shows an emergency relief station at Honkawa National School, which was close to the hypocenter. The photo is believed to have been taken in August 1945, by the late Toshio Kawamoto, a member of the Hiroshima Prefectural Police Department’s photography team. The photo is one that the Peace Memorial Museum did not have. Aerial photos taken by the U.S. military show the fire-devastated city from different angles and altitudes. By comparing and analyzing the images, new information on the damage can be obtained.

“These photos were taken to understand the effects of the bombing from a military point of view, but we would like to position them as materials to understand the horrors of the atomic bombing,” said Ryo Koyama, 39, a curator at the museum. There will be no end to efforts made at retrieving materials that can be used to fill “the voids.”

--------------------

Facilities in Hiroshima struggle with materials storage

Facility to keep such materials necessary

If the materials were to be collected systematically and passed down to future generations, new facts could be brought to light. Some new discoveries should be possible as technology advances. “Preservation” of the materials in and of itself is equivalent to unceasing efforts to learn lessons from the past. Nevertheless, some photos and documents are on the verge of being scattered and lost. Pathological specimens are deteriorating over time. What is the status of those materials in Hiroshima?

Medical materials include medical charts based on examinations of survivors, organ and tissue specimens and findings, as well as such biosamples as blood and urine. In Hiroshima, Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, located in Minami Ward, and three other facilities store most of such materials.

A-bomb survivors must live their entire lives carrying the burden of potential effects from A-bomb radiation on their health. The amount of related materials is huge. All the facilities have been struggling to secure space for storing the ever-increasing volume. Digitization of medical charts is underway to ensure that the materials are preserved and utilized. As some medical charts are stored at other facilities, some argue that it is necessary to grasp the present situation and set up measures to preserve them.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in Naka Ward, has been collecting photos of the terrible sights after the atomic bombing as well as personal belongings of victims. Such materials can be seen in the museum’s database on its website. Photos of Hiroshima’s cityscapes before the bombing are also kept at the Hiroshima Municipal Archives and the Hiroshima Central Municipal Library.

Information about the reality of the atomic bombing includes accounts written by survivors and victims’ family members. The Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, which is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, has been collecting such written information. On the other hand, public documents on relief measures for survivors and those on activities of survivor groups are on the verge of being scattered or discarded, as such groups are dissolving because of the advanced ages of survivors. People are also calling for adequate facilities for preserving materials related to literary works on the atomic bombing written while press censorship was being eluded during the occupation.

A great variety of large quantities of materials are stored in different locations. How can they be utilized? In 1971, the Science Council of Japan advised the national government that it was a pressing need for Japan to create atomic and hydrogen bomb victim materials centers in Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Tokyo. This advice matched the awareness of the problem held by scientists in the A-bombed cities. The only measure adopted, however, was expansion of the existing facilities at Hiroshima University. The task of the A-bombed nation of Japan, which systematically collects, organizes, and stores such materials, remains unfinished.

Materials related to Hiroshima returned from the U.S. in 1973

・Medical record holders of 9,060 people

・Organ samples preserved in formalin of 35 people

・Paraffin blocks of 284 people

・Slides of 669 people

・1,205 photographs (film)

※According to a 1973 report by the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine at Hiroshima University

(Originally published on April 6, 2020)