Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Duty passed on to next generations, Part 3: Use of materials

Jun. 18, 2020

Reality hidden in publicly available information

Preserving materials systematically together with the national government

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Yuji Yamamoto, and Kana Kobayashi, Staff Writers

Accounts of A-bomb survivors, photographs, research papers, and medical samples. Through interviews and research, the Chugoku Shimbun has become keenly aware of the importance of preservation of such various materials for understanding the reality of the damage caused by the atomic bombing and the path taken by Hiroshima after World War II.

Many shops and private homes stood in the former Tenjin-machi area, located around the present-day east building of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in the city’s Naka Ward, until the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. As part of events to mark the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing, the Hiroshima City government planned to publicly exhibit A-bombed remains such as burned and destroyed earthen walls of houses.

Published materials have clues

A sign in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park explains the former Tenjin-machi area, and a map titled “Reconstruction of Townscape near the Hypocenter” shows details of the area’s appearance before the bombing. This map was created on the basis of a series of articles by the Chugoku Shimbun about 20 years ago. Upon closer inspection, it is obvious there remain blank “voids” at 66 Tenjin-machi. Confirmation of the families that lived there prior to the bombing has not been possible.

The number of the area’s former residents able to share their A-bomb accounts has decreased. Does that mean further confirmation is difficult? That question crossed our mind, but clues do exist. A book with the title Hibakusha no Jinsei wo Sasaeta Mono (Things that Supported Hibakusha Lives) was published in 2018 by clinical psychotherapists practicing in Hiroshima. One A-bomb account by the late Setsuro Okusa described the A-bomb deaths of his grandfather Sangoro and his grandmother Tame, who lived at 66 Tenjin-machi.

That location is literally right next to the A-bombed remains that the city government is planning to exhibit to the public. The exhibit, however, is to be postponed until fiscal 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic. “We would like the city government to make a serious effort to collect data on the people who lived there and in its environs and whether they fell victim to the atomic bombing,” said Shunsuke Taga, 70, a resident of Nishi Ward who belongs to a group that promotes the exhibit of A-bomb remains. “We also want to offer our support.”

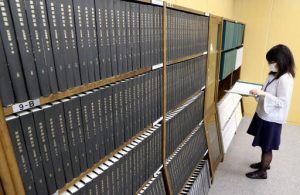

The reality is hiding in plain sight, not only in accounts of A-bomb survivors but also in publicly available information, including materials published in the past. The Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims possesses more than 140,000 A-bomb survivor accounts. Other materials are scattered throughout Japan. If they can be collected and used to continue work on carefully checking names of A-bomb victims, such voids in information can be filled to an even greater extent.

One of us traveled to the Korean Peninsula, which was once under Japan’s colonial rule. Inside the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association, in Hapcheon, South Korea, are stored a large number of documents that detail what happened to association members and their families in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Included in the documents are A-bomb victims not completely comprehended by the Hiroshima City government.

Students from Yeungnam University, located in South Korea, digitized a portion of the documents and compiled the information into booklets. The booklets, creation of which was painstaking work, were donated to the association in February 2020. Graduate student Kim Dongho, 28, said he wanted people to know of the existence of Korean A-bomb survivors and the fact that they have suffered for so long. Dr. Choi Bun Sum, a professor at the university, said he wanted the Japanese and South Korean governments to work in close cooperation at both the national and the local levels to utilize the booklets.

Witnesses can never be recovered

While the materials’ significance was brought into focus, we also recognized that, prior to the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing, many materials were at a crossroads in terms of their preservation. Many memoirs and records of activities that A-bomb survivors have written and stored in their homes are facing the end of the lives of their owners. Nonetheless, the materials continue to deteriorate. With cooperation from all those concerned, it is necessary to find the next resting place for such materials.

Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM), in the city’s Minami Ward, has been concerned that tissue samples from victims of the atomic bombing have deteriorated over time. The materials were seized by the U.S. military during the occupation and returned to Japan about 30 years later. The university’s budget, however, is limited. When we reported on the present conditions, Koki Inai, 71, emeritus professor at Hiroshima University and a board member of a medical non-profit organization, offered to cooperate in the process involving digitization of such materials. The information is expected to be utilized in new research in the future.

A-bomb survivors are calling for preservation of the four A-bombed former Army Clothing Depot buildings owned by Hiroshima Prefecture and Japan’s national government, as well as preservation of numerous photos of the city taken before the atomic bombing that are stored in both public institutions and private homes. Such examples of information, which cannot be brought back once lost, can be considered witnesses to the history of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima. People have been calling for multi-tiered and systematic preservation of such materials, with Japanese national government involvement, for more than 50 years.

Development of the internet has made it remarkably easy to exchange information on a global scale. Perhaps it is possible to design a space where both the government and civil society can consider from the A-bombed city what to do to create appropriate records, fill voids in information, and have people in the future be in a position to verify history.

(Originally published on June 18, 2020)