Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Drawing lines to define A-bomb survivors, Part 1: Victims left out of support

Jan. 3, 2021

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

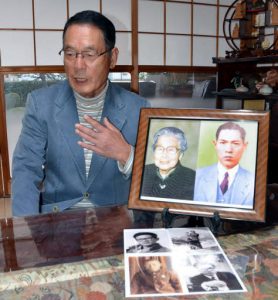

“What happened to my brothers’ bodies?” Takeshi Okimura, 75, a resident of the area of Aita in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward, lost two older brothers to cancer. Both Masaaki and Kazuo were 33 years old when they died. The family cannot dispel the doubt they died because “black rain,” with its radioactive particles, had entered their bodies. The family has been afflicted with the idea ever since August 6, 1945.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Masaaki was a fourth-year student at Yasu National School (now Yasu Elementary School), and Kazuo was in his second year. After the atomic bombing, they came home from school and went to an agricultural weir behind which black river water had collected. The brothers played there until early evening scooping up dead fish that had floated to the surface. Mr. Okimura was four months old then and at home. Later, he heard from his mother Akiko (who died in 1998 at the age of 88) that “the two had returned home smeared black.”

However, the Okimura family had no time to be concerned with black rain, because their oldest son Hiroshi, then 12, had not returned home. He was a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School. On that day, he was mobilized to Nakajima Shinmachi (now part of Naka Ward) with other students to help demolish houses to create fire lanes as part of the war effort. Despite the search starting early the next morning, the family could not find Hiroshi. They picked up a torn piece of a belt at the site where he had been working, and buried it in a grave. Their father, Masao, who had walked around searching for Hiroshi, was exposed to the atomic bombing at Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward) and died in 1960 at the age of 56.

In 1968, Masaaki died of pancreatic cancer. In 1971, three years after Masaaki’s death, Kazuo died from cancer of the small intestine. Nevertheless, Mr. Okimura “did not think their deaths were related to black rain.” In fact, it was not until the mid-1970s that more and more people became concerned about the association between health problems and black rain.

Movement demanding assistance for those exposed to black rain

In 1973, the Hiroshima City government launched a survey into the actual conditions of black rain in the town of Numata (now part of Asaminami Ward) and other parts of the city based on demands by residents. In 1976, Japan’s national government designated a heavy rain area, in which heavy black rain fell, based on surveys conducted by the Hiroshima District Meteorological Observatory (now Hiroshima Local Meteorological Observatory) in 1945, deciding to provide assistance only to the people who were in that area at the time. Calling for assistance, people who were exposed to black rain outside the designated area began to take earnest action, including the publication of a collection of accounts of their experiences.

However, Japan’s national government denied there was health damage for people outside the designated area at the time of the bombing. A framework to aid those directly exposed to the atomic bombing was gradually developed, and scientific knowledge was steadily accumulated including recognition of increased incidences of leukemia and cancers among that population. In contrast, however, black rain was never included in official records or as a topic of scientific study.

The “voids” that exist in relation to records and research make it difficult to verify the damage retrospectively. Last November, Japan’s national government announced it would analyze survivors’ medical records stored at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, as part of a new verification process. However, the hospital keeps records of only Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate holders. In the Okimura family, Masao was the only person exposed to the atomic bombing directly who had been examined at the Red Cross Hospital at that time.

In 2008, Hiroshima City and Hiroshima Prefecture conducted a large-scale survey on approximately 37,000 people asking questions about whether they had been exposed to black rain or were suffering from mental and physical health issues. Although the extensive survey results indicated that people who were exposed to black rain suffered from health disorders, Japan’s national government rebuffed the findings, based on its contention that “the findings do not constitute acceptable reasonable grounds.”

Materials need to be uncovered

How can we fill the “voids?” Satoru Ubuki, 74, former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who has studied A-bomb-related materials, suggested, “The central government should allot a budget to uncover medical records at clinics that treated those who experienced black rain” because they represent materials in which symptoms and other conditions were recorded objectively.

Tsuyoshi Harada, 83, a resident of the area of Yahata in Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward, was a second-year student at a national school. He had suffered extreme fatigue, with vomiting and diarrhea for some time after the bombing. Although he was diagnosed with a “duodenal ulcer” at a local medical clinic where he was an outpatient for two years, he still suspects his health issues were caused by black rain.

As the clinic no longer exists, we searched for his attending physician’s family and asked them if they still had his medical records. Their response: “We’re not sure because the atomic bombing happened two generations ago.” Many local residents exposed to black rain were under a physician’s care, but their medical records have already been disposed of because the records-retention period stipulated by the Japan’s Medical Practitioners Act is five years.

“There is no evidence they died because of the atomic bombing, but…” Akiko Okimura, the mother who lost two sons to cancer, expressed her regrets in her memoir written two years before her death. The “evidence” might remain somewhere as a series of medical records. Presently, however, many clinics have closed because no one was around to take over the business.

◇

In contrast to direct exposure, on which much research has been conducted, health effects of indirect exposure, including “black rain,” are still poorly understood. What can be done now will be explored.

(Originally published on January 3, 2021)

Lack of records about black rain represents obstacle—Medical records of victims continue to be dispersed and lost

“What happened to my brothers’ bodies?” Takeshi Okimura, 75, a resident of the area of Aita in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward, lost two older brothers to cancer. Both Masaaki and Kazuo were 33 years old when they died. The family cannot dispel the doubt they died because “black rain,” with its radioactive particles, had entered their bodies. The family has been afflicted with the idea ever since August 6, 1945.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Masaaki was a fourth-year student at Yasu National School (now Yasu Elementary School), and Kazuo was in his second year. After the atomic bombing, they came home from school and went to an agricultural weir behind which black river water had collected. The brothers played there until early evening scooping up dead fish that had floated to the surface. Mr. Okimura was four months old then and at home. Later, he heard from his mother Akiko (who died in 1998 at the age of 88) that “the two had returned home smeared black.”

However, the Okimura family had no time to be concerned with black rain, because their oldest son Hiroshi, then 12, had not returned home. He was a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School. On that day, he was mobilized to Nakajima Shinmachi (now part of Naka Ward) with other students to help demolish houses to create fire lanes as part of the war effort. Despite the search starting early the next morning, the family could not find Hiroshi. They picked up a torn piece of a belt at the site where he had been working, and buried it in a grave. Their father, Masao, who had walked around searching for Hiroshi, was exposed to the atomic bombing at Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward) and died in 1960 at the age of 56.

In 1968, Masaaki died of pancreatic cancer. In 1971, three years after Masaaki’s death, Kazuo died from cancer of the small intestine. Nevertheless, Mr. Okimura “did not think their deaths were related to black rain.” In fact, it was not until the mid-1970s that more and more people became concerned about the association between health problems and black rain.

Movement demanding assistance for those exposed to black rain

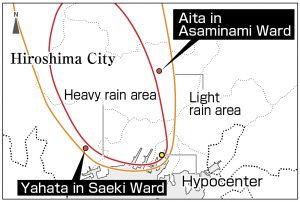

In 1973, the Hiroshima City government launched a survey into the actual conditions of black rain in the town of Numata (now part of Asaminami Ward) and other parts of the city based on demands by residents. In 1976, Japan’s national government designated a heavy rain area, in which heavy black rain fell, based on surveys conducted by the Hiroshima District Meteorological Observatory (now Hiroshima Local Meteorological Observatory) in 1945, deciding to provide assistance only to the people who were in that area at the time. Calling for assistance, people who were exposed to black rain outside the designated area began to take earnest action, including the publication of a collection of accounts of their experiences.

However, Japan’s national government denied there was health damage for people outside the designated area at the time of the bombing. A framework to aid those directly exposed to the atomic bombing was gradually developed, and scientific knowledge was steadily accumulated including recognition of increased incidences of leukemia and cancers among that population. In contrast, however, black rain was never included in official records or as a topic of scientific study.

The “voids” that exist in relation to records and research make it difficult to verify the damage retrospectively. Last November, Japan’s national government announced it would analyze survivors’ medical records stored at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, as part of a new verification process. However, the hospital keeps records of only Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate holders. In the Okimura family, Masao was the only person exposed to the atomic bombing directly who had been examined at the Red Cross Hospital at that time.

In 2008, Hiroshima City and Hiroshima Prefecture conducted a large-scale survey on approximately 37,000 people asking questions about whether they had been exposed to black rain or were suffering from mental and physical health issues. Although the extensive survey results indicated that people who were exposed to black rain suffered from health disorders, Japan’s national government rebuffed the findings, based on its contention that “the findings do not constitute acceptable reasonable grounds.”

Materials need to be uncovered

How can we fill the “voids?” Satoru Ubuki, 74, former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who has studied A-bomb-related materials, suggested, “The central government should allot a budget to uncover medical records at clinics that treated those who experienced black rain” because they represent materials in which symptoms and other conditions were recorded objectively.

Tsuyoshi Harada, 83, a resident of the area of Yahata in Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward, was a second-year student at a national school. He had suffered extreme fatigue, with vomiting and diarrhea for some time after the bombing. Although he was diagnosed with a “duodenal ulcer” at a local medical clinic where he was an outpatient for two years, he still suspects his health issues were caused by black rain.

As the clinic no longer exists, we searched for his attending physician’s family and asked them if they still had his medical records. Their response: “We’re not sure because the atomic bombing happened two generations ago.” Many local residents exposed to black rain were under a physician’s care, but their medical records have already been disposed of because the records-retention period stipulated by the Japan’s Medical Practitioners Act is five years.

“There is no evidence they died because of the atomic bombing, but…” Akiko Okimura, the mother who lost two sons to cancer, expressed her regrets in her memoir written two years before her death. The “evidence” might remain somewhere as a series of medical records. Presently, however, many clinics have closed because no one was around to take over the business.

◇

In contrast to direct exposure, on which much research has been conducted, health effects of indirect exposure, including “black rain,” are still poorly understood. What can be done now will be explored.

(Originally published on January 3, 2021)