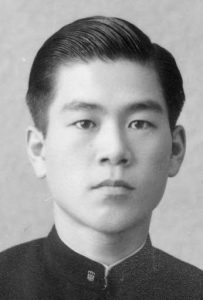

Survivors’ Stories: Masaru Nanko, 90, Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima, incinerated brother’s corpse with empty mind

May 10, 2021

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Masaru Nanko, 90, lost his younger brother Osamu, who was 12 at the time, in the atomic bombing. “The United States dropped the atomic bomb despite knowing the ‘inhumane consequences’ that would result. I will never forgive them.” In letters to newspaper editors, Mr. Nanko has repeatedly expressed his anger using such language.

At the time, Mr. Nanko was 14 and a third-year student at the First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School). Few classes were provided at that time, and even junior high-school students had been mobilized to work in munitions factories for the war effort. Mr. Nanko worked at Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation) in the area of Fuchu-cho. There, he observed many conscripted laborers from the Korean Peninsula.

On August 6, 1945, Mr. Nanko was carrying finished rifles to an underground firing range. He suddenly saw a bluish-white light, following which the area was engulfed in pitch darkness. Soon, an order went out requesting the students to return to their homes. He traveled along Ozu Roadway, heading to his home in the town of Ujina-machi (now part of Minami Ward, Hiroshima).

As he passed by people frantically trying to find refuge, Mr. Nanko witnessed a gigantic cloud spreading above Hijiyama Hill. He arrived back at his home sometime before noon. Osamu, then a first-year student at the First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School, had not yet returned. He had been at work near the neighborhood of Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward), about one kilometer from the hypocenter, helping to demolish buildings to create fire lanes.

In search of his brother, Mr. Nanko went as far as Miyuki Bridge but then turned back because the area was teeming with wounded people and flames were starting to spread on the other side of the bridge. He and his mother Shizuko waited for Osamu in front of their house on Miyuki-dori street. At around 2:30 p.m., an unknown man approached them. Carrying Osamu on the rack of his bicycle, the man said, “He had sought refuge at Danbara.”

“Osamu is back!” Shizuko hastily held her son in her arms and placed him on a Japanese futon. Osamu was in only his underpants, with his skin hanging down in strips like tatters and his face and head red and swollen. He held tightly in his hands a leather belt. It was a gift from his parents in celebration of his passing the entrance exam for junior high school.

They heard someone walking around announcing that “The burned will die if they drink water.” All they could do was moisten Osamu’s mouth using a piece of gauze soaked with water. Osamu died the evening of August 6, after momentarily spreading his arms out wide. “He might have been using a hand flag signal he had learned in the Sea Scouts to say ‘Goodbye,’” Mr. Nanko explained. Osamu was apparently an active child who often played the main character in school plays.

It was late at night by the time Mr. Nanko’s older brother Takashi returned home after walking from the naval dockyard in Kure City, where he had been mobilized. The three members of the family stayed with Osamu’s remains through the night. In the evening of the next day, Mr. Nanko and Takashi carried Osamu’s remains to a vacant lot near the house. They collected scrap wood and cremated the body. Smoke billowed everywhere. Mr. Nanko recalled that moment. “I just burned his remains. My mind was blank, with no sense of sorrow. The war had warped my senses.”

After World War II, Mr. Nanko studied political science and economics at the newly reorganized Hiroshima University. In 1953, he started work at Hiroshima Bank, mainly in the investigative department. He engaged in work related to the restoration of local companies and ultimately served as senior managing director. He married Takayo, who was seven years his junior, when he was 29. The couple had one son and three daughters. However, in 1999, at the age of 61, Takayo died of acute myeloid leukemia. Some physicians suggested that her death was associated with her exposure to the atomic bombing when she was a child.

The belt Osamu had gripped tightly was kept in the family Buddhist altar as a memento. Shizuko took it out every morning and evening, touching and clasping it tightly to her chest. In 2004, she and Mr. Nanko donated the belt to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in the hopes that it would “be made good use of for posterity.” Five years later, Shizuko died at the age of 102. Until recently, the belt had been displayed in the permanent exhibition of the museum.

The atomic bomb killed 353 students of the First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School. “Innocent students died tragic deaths. What happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki must not be forgotten,” Mr. Nanko has said. Japan’s national government believes that the “nuclear umbrella” provided by the United States, the country that used the atomic bombs, will protect the country. Mr. Nanko, who now is more than 90, feels ever more strongly that “Japan must never forget its duty and responsibilities as the A-bombed nation.”

(Originally published on May 10, 2021)

Still angry at U.S. for A-bombing despite its knowledge of “inhumane consequences” that would result

Masaru Nanko, 90, lost his younger brother Osamu, who was 12 at the time, in the atomic bombing. “The United States dropped the atomic bomb despite knowing the ‘inhumane consequences’ that would result. I will never forgive them.” In letters to newspaper editors, Mr. Nanko has repeatedly expressed his anger using such language.

At the time, Mr. Nanko was 14 and a third-year student at the First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School). Few classes were provided at that time, and even junior high-school students had been mobilized to work in munitions factories for the war effort. Mr. Nanko worked at Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation) in the area of Fuchu-cho. There, he observed many conscripted laborers from the Korean Peninsula.

On August 6, 1945, Mr. Nanko was carrying finished rifles to an underground firing range. He suddenly saw a bluish-white light, following which the area was engulfed in pitch darkness. Soon, an order went out requesting the students to return to their homes. He traveled along Ozu Roadway, heading to his home in the town of Ujina-machi (now part of Minami Ward, Hiroshima).

As he passed by people frantically trying to find refuge, Mr. Nanko witnessed a gigantic cloud spreading above Hijiyama Hill. He arrived back at his home sometime before noon. Osamu, then a first-year student at the First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School, had not yet returned. He had been at work near the neighborhood of Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward), about one kilometer from the hypocenter, helping to demolish buildings to create fire lanes.

In search of his brother, Mr. Nanko went as far as Miyuki Bridge but then turned back because the area was teeming with wounded people and flames were starting to spread on the other side of the bridge. He and his mother Shizuko waited for Osamu in front of their house on Miyuki-dori street. At around 2:30 p.m., an unknown man approached them. Carrying Osamu on the rack of his bicycle, the man said, “He had sought refuge at Danbara.”

“Osamu is back!” Shizuko hastily held her son in her arms and placed him on a Japanese futon. Osamu was in only his underpants, with his skin hanging down in strips like tatters and his face and head red and swollen. He held tightly in his hands a leather belt. It was a gift from his parents in celebration of his passing the entrance exam for junior high school.

They heard someone walking around announcing that “The burned will die if they drink water.” All they could do was moisten Osamu’s mouth using a piece of gauze soaked with water. Osamu died the evening of August 6, after momentarily spreading his arms out wide. “He might have been using a hand flag signal he had learned in the Sea Scouts to say ‘Goodbye,’” Mr. Nanko explained. Osamu was apparently an active child who often played the main character in school plays.

It was late at night by the time Mr. Nanko’s older brother Takashi returned home after walking from the naval dockyard in Kure City, where he had been mobilized. The three members of the family stayed with Osamu’s remains through the night. In the evening of the next day, Mr. Nanko and Takashi carried Osamu’s remains to a vacant lot near the house. They collected scrap wood and cremated the body. Smoke billowed everywhere. Mr. Nanko recalled that moment. “I just burned his remains. My mind was blank, with no sense of sorrow. The war had warped my senses.”

After World War II, Mr. Nanko studied political science and economics at the newly reorganized Hiroshima University. In 1953, he started work at Hiroshima Bank, mainly in the investigative department. He engaged in work related to the restoration of local companies and ultimately served as senior managing director. He married Takayo, who was seven years his junior, when he was 29. The couple had one son and three daughters. However, in 1999, at the age of 61, Takayo died of acute myeloid leukemia. Some physicians suggested that her death was associated with her exposure to the atomic bombing when she was a child.

The belt Osamu had gripped tightly was kept in the family Buddhist altar as a memento. Shizuko took it out every morning and evening, touching and clasping it tightly to her chest. In 2004, she and Mr. Nanko donated the belt to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in the hopes that it would “be made good use of for posterity.” Five years later, Shizuko died at the age of 102. Until recently, the belt had been displayed in the permanent exhibition of the museum.

The atomic bomb killed 353 students of the First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School. “Innocent students died tragic deaths. What happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki must not be forgotten,” Mr. Nanko has said. Japan’s national government believes that the “nuclear umbrella” provided by the United States, the country that used the atomic bombs, will protect the country. Mr. Nanko, who now is more than 90, feels ever more strongly that “Japan must never forget its duty and responsibilities as the A-bombed nation.”

(Originally published on May 10, 2021)