Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima—Former Chugoku Shimbun journalist Natsue Yashima wrote account of “Kudentai” 33 years after A-bombing

Apr. 5, 2021

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Further details have been uncovered about the Chugoku Shimbun’s woman journalist who was a member of “Kudentai,” a group that traveled around Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing to orally communicate information about the devastation to affected citizens. Her name was Natsue Yashima, and she worked in the newspaper’s copy editing department (dying at the age of 87 in 2006). Thirty-three years after the bombing, Ms. Yashima wrote an account of her Kudentai work, which she described as involving delivery of an “oral newspaper.” She submitted the account to the prefectural offices in Hyogo Prefecture, her home at the time, upon her application for an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. Disclosure of her account was permitted based on cooperation from her oldest son. As for Kudentai, no personal accounts featuring the group have been discovered even at the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, a facility in which more than 147,000 such accounts of A-bomb survivors are stored.

According to Ms. Yashima’s account, on August 6, 1945, around 8:00 p.m., when Ms. Yashima was at her friend’s home near the entrance of Sandankyo Gorge in the town of Togouchi-cho (now part of Akiota-cho), Hiroshima Prefecture, she heard news about the unusual situation occurring in Hiroshima. She headed to the city by sharing with others rides on an aid truck and a river boat.

She arrived in Hiroshima’s area of Yokogawa-cho (now part of Nishi Ward) around 1:00 p.m. on August 7. She headed toward the Chugoku Shimbun office building, a 7-story ferroconcrete building standing amidst the ruins, and reached the neighboring area of Hiratsuka-cho (now part of Naka Ward), where she lived with her mother and older sisters. She wrote, “There were no bodies around my home or the neighborhood. I became convinced my mother was still alive and finally felt encouraged. I then returned (to the office).”

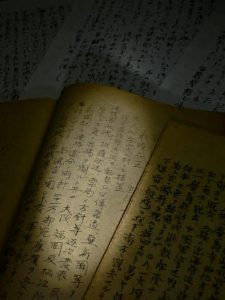

With others who had survived, she formed Kudentai with the desire to communicate news orally amid the absence of any paper at that time. She wrote, “We gathered the news, rode on separate trucks, and delivered the news verbally. We continued this activity until the day the war ended.” She also described in her account on seven pages of stationary the symptoms of acute radiation damage she had experienced, attaching the notes to an application for an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate she submitted in 1978.

Kudentai was established amid unprecedented circumstances with a wartime organizational structure that unified the military, government, and the private sector. Genshin Takano, then Hiroshima governor, wrote a report (dated August 21, 1945) to the Japan Home Ministry and the Second General Military Headquarters located at the area of the present-day Higashi Ward. In the report, Mr. Takano described the oral communication of news as one of the measures taken immediately after the bombing, in addition to medical relief operations and disposal of corpses.

The Chugoku Shimbun’s headquarters had been burned to the ground. The company resumed its publishing work after printing its newspaper dated August 9, three days after the devastation of Hiroshima, by using printing presses at the Seibu (West) headquarters of two other newspaper companies—the Asahi Shimbun and the Mainichi Shimbun (located in present-day Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture)—in place of its own printers. However, information on rescue operations and food supplies, so desperately needed by A-bomb survivors, was not covered in the paper. Kudentai worked to fill that void in information by communicating such news.

In the book titled “Chugoku Shimbun 65-nen Shi” (in English as the 65-year history of the Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper), published in 1956, names of four employees, three men and one woman, were described as being the Kudentai members who held a megaphone in one hand and orally reported the news until they became hoarse. For Natsue Yashima, no records of her joining or resigning from the company, or of her age, remain.

Since the atomic bombing, 76 years have passed. By tracing Natsue Yashima’s history, it became possible to uncover not only the actions of the newspaper reporter facing such an unprecedented situation but also about how ongoing A-bombing news coverage got its start in Hiroshima. More details about this story will be covered in a series of articles starting with this one today.

News coverage in aftermath of the atomic bombing

About the new weapon, the Japanese Imperial Headquarters made an official announcement at 3:30 p.m. on August 7, 1945, one day after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Newspapers carried the news at the top of their front page on August 8. Due to wartime press controls, the term “atomic bomb” appeared in only a few newspapers on August 11. As soon as the war ended on August 15, articles and photographs featuring the catastrophe of Hiroshima appeared in newspapers one after the other. The Chugoku Shimbun resumed its publishing work after printing its newspaper dated August 9, by utilizing sections of the Asahi Shimbun and the Mainichi Shimbun for carrying its news in place of its typical format. An Asahi Shimbun journalist from Fukuoka Prefecture also participated in Kudentai’s efforts.

(Originally published on April 5, 2021)

Kudentai “oral newspaper” delivered immediately after catastrophe

Further details have been uncovered about the Chugoku Shimbun’s woman journalist who was a member of “Kudentai,” a group that traveled around Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing to orally communicate information about the devastation to affected citizens. Her name was Natsue Yashima, and she worked in the newspaper’s copy editing department (dying at the age of 87 in 2006). Thirty-three years after the bombing, Ms. Yashima wrote an account of her Kudentai work, which she described as involving delivery of an “oral newspaper.” She submitted the account to the prefectural offices in Hyogo Prefecture, her home at the time, upon her application for an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. Disclosure of her account was permitted based on cooperation from her oldest son. As for Kudentai, no personal accounts featuring the group have been discovered even at the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, a facility in which more than 147,000 such accounts of A-bomb survivors are stored.

According to Ms. Yashima’s account, on August 6, 1945, around 8:00 p.m., when Ms. Yashima was at her friend’s home near the entrance of Sandankyo Gorge in the town of Togouchi-cho (now part of Akiota-cho), Hiroshima Prefecture, she heard news about the unusual situation occurring in Hiroshima. She headed to the city by sharing with others rides on an aid truck and a river boat.

She arrived in Hiroshima’s area of Yokogawa-cho (now part of Nishi Ward) around 1:00 p.m. on August 7. She headed toward the Chugoku Shimbun office building, a 7-story ferroconcrete building standing amidst the ruins, and reached the neighboring area of Hiratsuka-cho (now part of Naka Ward), where she lived with her mother and older sisters. She wrote, “There were no bodies around my home or the neighborhood. I became convinced my mother was still alive and finally felt encouraged. I then returned (to the office).”

With others who had survived, she formed Kudentai with the desire to communicate news orally amid the absence of any paper at that time. She wrote, “We gathered the news, rode on separate trucks, and delivered the news verbally. We continued this activity until the day the war ended.” She also described in her account on seven pages of stationary the symptoms of acute radiation damage she had experienced, attaching the notes to an application for an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate she submitted in 1978.

Kudentai was established amid unprecedented circumstances with a wartime organizational structure that unified the military, government, and the private sector. Genshin Takano, then Hiroshima governor, wrote a report (dated August 21, 1945) to the Japan Home Ministry and the Second General Military Headquarters located at the area of the present-day Higashi Ward. In the report, Mr. Takano described the oral communication of news as one of the measures taken immediately after the bombing, in addition to medical relief operations and disposal of corpses.

The Chugoku Shimbun’s headquarters had been burned to the ground. The company resumed its publishing work after printing its newspaper dated August 9, three days after the devastation of Hiroshima, by using printing presses at the Seibu (West) headquarters of two other newspaper companies—the Asahi Shimbun and the Mainichi Shimbun (located in present-day Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture)—in place of its own printers. However, information on rescue operations and food supplies, so desperately needed by A-bomb survivors, was not covered in the paper. Kudentai worked to fill that void in information by communicating such news.

In the book titled “Chugoku Shimbun 65-nen Shi” (in English as the 65-year history of the Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper), published in 1956, names of four employees, three men and one woman, were described as being the Kudentai members who held a megaphone in one hand and orally reported the news until they became hoarse. For Natsue Yashima, no records of her joining or resigning from the company, or of her age, remain.

Since the atomic bombing, 76 years have passed. By tracing Natsue Yashima’s history, it became possible to uncover not only the actions of the newspaper reporter facing such an unprecedented situation but also about how ongoing A-bombing news coverage got its start in Hiroshima. More details about this story will be covered in a series of articles starting with this one today.

Keywords

News coverage in aftermath of the atomic bombing

About the new weapon, the Japanese Imperial Headquarters made an official announcement at 3:30 p.m. on August 7, 1945, one day after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Newspapers carried the news at the top of their front page on August 8. Due to wartime press controls, the term “atomic bomb” appeared in only a few newspapers on August 11. As soon as the war ended on August 15, articles and photographs featuring the catastrophe of Hiroshima appeared in newspapers one after the other. The Chugoku Shimbun resumed its publishing work after printing its newspaper dated August 9, by utilizing sections of the Asahi Shimbun and the Mainichi Shimbun for carrying its news in place of its typical format. An Asahi Shimbun journalist from Fukuoka Prefecture also participated in Kudentai’s efforts.

(Originally published on April 5, 2021)