Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima—Kudentai’s work in August 1945, Part 3: A-bomb journalist

Apr. 7, 2021

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Natsue Yashima, then 27, who worked as a member of the Kudentai group in Hiroshima soon after the city’s devastation in the atomic bombing, returned to her work at the Chugoku Shimbun after she recovered from acute radiation health effects. Thirty-three years after her A-bombing experience, she wrote in her account of those times, “I was able to walk again around the middle of October.”

After its headquarters were burned to the ground in the atomic bombing, the Chugoku Shimbun resumed the printing of the newspaper on its own dated September 3, 1945, using a printing press that the company had evacuated to the village of Nukushina (now part of Higashi Ward), in Hiroshima’s suburbs. However, because the area was damaged by flooding when the Makurazaki Typhoon hit on September 17, publication had to be suspended.

Company employees returned to the city’s downtown area, which was still covered in ruins, and began publication of the newspaper on November 5 at the headquarters on their own. Under the headline “When will restoration of our hometown take place?,” at the top of its second page, filled with information sought by the A-bomb survivors, the paper called for increasing the supply of shelter and clothing to ward off the cold and food to mitigate famine.

One might wonder whether Ms. Yashima was recognized for the hard work of risking her life to report for Kudentai. She was appointed as a junior employee, according to the original record of announced appointments as of December 1945, one month after publication of the newspaper resumed at the headquarters. She had been promoted from the position of non-regular employee, her job title until that time. In the staff register at the headquarters as of March 1946, she was listed as the only woman among six employees in the copy editing department, which was responsible for editing the newspaper content. However, no further records have been found about her since that time.

“She told me she had been asked to stay on but did not hesitate to resign. She was an independent person until the end of her life,” said Daijo Yamada, 66, a painter and Ms. Yashima’s oldest son, when a reporter visited him at his house in Tokyo and asked about the nature of his now-deceased mother.

Applied for issuance of Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate at age 60

Based on her own talents, Ms. Yashima, the A-bomb journalist, moved through the newspaper industry, which was flourishing with many new entrants due to the democratization that took root after the war.

Ms. Yashima resigned from the Chugoku Shimbun in her hometown and joined the Kyoto Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, a newly established evening newspaper, in October 1946. After that company merged with the Kyoto Shimbun in 1949, she continued to work at the copy editing department there but resigned the post voluntarily the following year. She began work at the Osaka Yomiuri Shimbun, which was established in 1952. She joined the company in 1953 and again worked at the copy editing department. In 1955, one year after she married and gave birth to her first son, she left the job.

Since Daijo had become a student in the upper grades of elementary school, she worked on editing and collecting information on books published by an associated company of the Kobe Shimbun. She continued to work as the primary breadwinner and financial support for her family of four, including her children and husband.

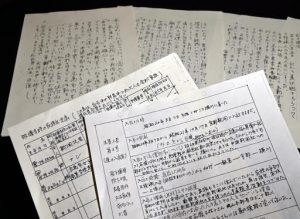

She applied to the Hyogo Prefectural office for an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate in 1978. She was 60 years old. In the ‘occupation’ box on the application form, she wrote “freelance editor.” For the reason why she had not applied for the certificate until that time, she wrote a statement in her note, as follows: “My older sister in Hiroshima experienced recurrence of A-bomb disease in the summer this year and was bedridden for a month. I had a fear there might be something I cannot be cured of, which made me decide to apply for the certificate.” In 1984, her sister Mitsue died at the age of 69.

Around the time his mother applied for the certificate, Mr. Yamada was a student at the Hokkaido University of Education. Looking back that time, he said, “When I asked her about the atomic bombing, she would discuss it, but she didn’t do so voluntarily.” After waiting for her children to grow up and become independent, she changed her name back to Yashima, her original family name.

At this time, he learned that she had become a member of Kudentai under those unprecedented circumstances. “I think it was just like my mother to have acted in such a way. She always tried to do whatever she could do,” said Mr. Yamada.

Moved to Okinawa before her death At the end of her life, for a period of 12 years, Ms. Yashima lived in Okinawa. She decided to move to Okinawa because Mr. Yamada, an art teacher, had established his artistic base on Ishigaki Island in Okinawa after returning from Costa Rica in Central America, where he lived for two-and-a-half years. She was full of curiosity and had strong legs. She enjoyed traveling alone even after turning 80.

On January 17, 2006, she died from lymphoma at a hospital in Okinawa. She was 87. In accordance with her will, her cremated ashes were scattered in Kabira Bay on Ishigaki Island.

(Originally published on April 7, 2021)

Pursued career as editor after end of war

“Independent person until end of her life”

Natsue Yashima, then 27, who worked as a member of the Kudentai group in Hiroshima soon after the city’s devastation in the atomic bombing, returned to her work at the Chugoku Shimbun after she recovered from acute radiation health effects. Thirty-three years after her A-bombing experience, she wrote in her account of those times, “I was able to walk again around the middle of October.”

After its headquarters were burned to the ground in the atomic bombing, the Chugoku Shimbun resumed the printing of the newspaper on its own dated September 3, 1945, using a printing press that the company had evacuated to the village of Nukushina (now part of Higashi Ward), in Hiroshima’s suburbs. However, because the area was damaged by flooding when the Makurazaki Typhoon hit on September 17, publication had to be suspended.

Company employees returned to the city’s downtown area, which was still covered in ruins, and began publication of the newspaper on November 5 at the headquarters on their own. Under the headline “When will restoration of our hometown take place?,” at the top of its second page, filled with information sought by the A-bomb survivors, the paper called for increasing the supply of shelter and clothing to ward off the cold and food to mitigate famine.

One might wonder whether Ms. Yashima was recognized for the hard work of risking her life to report for Kudentai. She was appointed as a junior employee, according to the original record of announced appointments as of December 1945, one month after publication of the newspaper resumed at the headquarters. She had been promoted from the position of non-regular employee, her job title until that time. In the staff register at the headquarters as of March 1946, she was listed as the only woman among six employees in the copy editing department, which was responsible for editing the newspaper content. However, no further records have been found about her since that time.

“She told me she had been asked to stay on but did not hesitate to resign. She was an independent person until the end of her life,” said Daijo Yamada, 66, a painter and Ms. Yashima’s oldest son, when a reporter visited him at his house in Tokyo and asked about the nature of his now-deceased mother.

Applied for issuance of Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate at age 60

Based on her own talents, Ms. Yashima, the A-bomb journalist, moved through the newspaper industry, which was flourishing with many new entrants due to the democratization that took root after the war.

Ms. Yashima resigned from the Chugoku Shimbun in her hometown and joined the Kyoto Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, a newly established evening newspaper, in October 1946. After that company merged with the Kyoto Shimbun in 1949, she continued to work at the copy editing department there but resigned the post voluntarily the following year. She began work at the Osaka Yomiuri Shimbun, which was established in 1952. She joined the company in 1953 and again worked at the copy editing department. In 1955, one year after she married and gave birth to her first son, she left the job.

Since Daijo had become a student in the upper grades of elementary school, she worked on editing and collecting information on books published by an associated company of the Kobe Shimbun. She continued to work as the primary breadwinner and financial support for her family of four, including her children and husband.

She applied to the Hyogo Prefectural office for an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate in 1978. She was 60 years old. In the ‘occupation’ box on the application form, she wrote “freelance editor.” For the reason why she had not applied for the certificate until that time, she wrote a statement in her note, as follows: “My older sister in Hiroshima experienced recurrence of A-bomb disease in the summer this year and was bedridden for a month. I had a fear there might be something I cannot be cured of, which made me decide to apply for the certificate.” In 1984, her sister Mitsue died at the age of 69.

Around the time his mother applied for the certificate, Mr. Yamada was a student at the Hokkaido University of Education. Looking back that time, he said, “When I asked her about the atomic bombing, she would discuss it, but she didn’t do so voluntarily.” After waiting for her children to grow up and become independent, she changed her name back to Yashima, her original family name.

At this time, he learned that she had become a member of Kudentai under those unprecedented circumstances. “I think it was just like my mother to have acted in such a way. She always tried to do whatever she could do,” said Mr. Yamada.

Moved to Okinawa before her death At the end of her life, for a period of 12 years, Ms. Yashima lived in Okinawa. She decided to move to Okinawa because Mr. Yamada, an art teacher, had established his artistic base on Ishigaki Island in Okinawa after returning from Costa Rica in Central America, where he lived for two-and-a-half years. She was full of curiosity and had strong legs. She enjoyed traveling alone even after turning 80.

On January 17, 2006, she died from lymphoma at a hospital in Okinawa. She was 87. In accordance with her will, her cremated ashes were scattered in Kabira Bay on Ishigaki Island.

(Originally published on April 7, 2021)