Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 76 years after the atomic bombing—Records of mobilized students at First Girls’ School, Part 1: Survivors’ guilt

Jul. 19, 2021

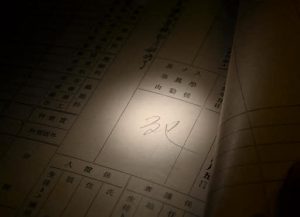

Only one word is written in pencil in the space for post-enrollment changes/reasons: “Death.” The school attendance registers that list most of the 541 first- and second-year students at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (First Girls’ School) who became victims of the atomic bombing when they helped with work to demolish buildings for fire lanes as mobilized students are archived at Funairi High School, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward.

Students hardly attended classes

The thickness of the materials speaks to the fact that many students died. Many columns in their report cards were left blank, meaning students at that time hardly had a chance to attend classes since entering the school.

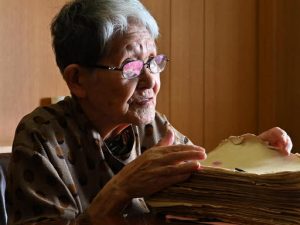

“I’m so grateful the records have been kept,” said Miyako Yano (née Ikeda), 90, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, when visiting her alma mater in late June and “meeting” the names of her two best friends listed in the school register. She was a second-year student at First Girls’ School at the time of the atomic bombing. Ms. Yano would go home from school with Yoshiko Fujimoto. They would jump off the Miyuki Bridge together into the river and swim, sometimes gathering double handfuls of freshwater clams. She would take a bath at Ms. Fujimoto’s house. Etsuko Morisaki lived near Ms. Yano’s house in the area of Ujina-machi.

That day completely changed everything.

On August 6, 1945, Ms. Yano decided to take the day off from school because she had been suffering from terrible diarrhea starting the night before. She asked Ms. Morisaki, who came for her to go to school, to submit a written note explaining her absence to the school. At 8:15 a.m., the U.S. military dropped the atomic bomb on the city and the students who were helping to demolish buildings on the south side of the present-day Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, approximately 500 meters from the hypocenter.

While it was impossible to recognize who was who, a torn piece of the loose work-pants worn by Ms. Morisaki helped in identifying her body. “A hard-working student died, and the one who skipped school survived” was an accusation Ms. Morisaki’s family hurled at Ms. Yano amid the confusion after the bombing. When Ms. Yano told Ms. Fujimoto’s sister that she had taken that day off, the sister collapsed in front of her.

On September 1, Ms. Yano attended school for the first time since the end of the war and found out that all her classmates mobilized to demolish buildings had been killed. “I was deeply shocked. I blamed myself for not going to do the work, even though I wasn’t in good shape health-wise, and not dying with them.” She and her friend who was in the same situation once tried to kill themselves. They sat down on the riverbank near the school, trying to throw themselves into the river. However, they could not get up the courage. When she came home after dark, she found out her family had been looking desperately for her, which broke her heart.

She tried to avoid being seen, shutting herself away from society, even covering her face with a mask whenever she went out. One day, however, she read a memoir written by the family of a deceased classmate and thought, “I might have met the same fate if it had been a day earlier or later. I must do what I can as an A-bomb survivor.” She roused herself and ever since has worked hard for the A-bomb survivors’ movement and in peace activities for more than half a century.

“We had been educated to believe it was an honor to die for the country. These children only had no other chance but to live amid war. No other children should be forced to endure the same fate,” Ms. Yano said, holding the school register with both hands.

Living unobtrusively even today

One survivor even today lives unobtrusively. The 88-year-old woman living in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward was in class number “Five” in the first grade of First Girls’ School. On August 6, she was absent from school because her mother felt unwell and begged her not to go. “Two friends, who came to pick me up, left for school saying, ‘It’s hot. We don’t want to go. We want to take a day off, too.’ I could never forget their voices and receding figures.” She has been blaming herself for being an “unpatriotic survivor” for 76 years.

In Hiroshima, 12- to 14-year-old boys and girls were forced to cooperate in the war effort, only to die in the atomic bombing. We would like everyone to think about the lessons that we, those who live in the present, should take to heart from the materials at that time that are stored at Funairi High School, as well as survivors’ testimonies and their A-bomb memoirs.

(Originally published on July 19, 2021)