Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing — “Shichotai” remnants, Part 4: Life at site

Jul. 16, 2021

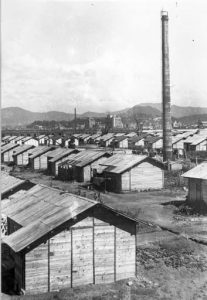

The photograph, taken in June 1947 of the east side of the Otagawa River in Hiroshima’s Motomachi district (now part of Naka Ward), shows rows of shacks made with plywood built on the site of the former Japanese Army’s transport unit known as the Chugoku District transport soldier recruitment unit (“Shichotai” in Japanese), which was totally destroyed in the atomic bombing. Construction of this simple public housing started in 1945 for war victims to ensure they could make it through the winter.

“It was a place for people who had nowhere else to go.” Kozaburo Nagatsu, 86, a resident of Iwakuni City and secretary-general of the Hiroshima Kageki no Kai, a Hiroshima-based group that celebrates the works of A-bomb author Tamiki Hara, who lived in the area between around 1948 and 1953, helping his father who operated a newspaper retail outlet.

One water supply shared by 20 homes

In 1946, the Hiroshima City government decided to make the entire area into a park. However, the former public housing authority and the governments of Hiroshima City and Hiroshima Prefecture gradually constructed houses as an emergency measure to deal with the housing shortage. About 1,800 houses were built in addition to those for providing shelter to residents in winter that had already been built. Illegally built houses also lined the riverbank. The area was later dubbed the “A-bomb slum.”

Mr. Nagatsu and his father lived in a single-story house first built at the site of the Shichotai unit for use as shelter in the winter. The house had two rooms, one four-and-a-half tatami mats and the other six mats in size, with an earthen floor and a toilet outside. There was a roof but no ceiling, and the walls had knotholes open to the outside. There was only one water supply line for 20 families. Horse bones were dug up from the fields in what might have been remains of the Shichotai unit.

In his poem titled “To a Lady,” the poet Sankichi Toge described an A-bombed woman living in a town of shacks on the site of the Shichotai unit. Mr. Nagatsu remembers “a woman just like her, working for the newspaper retail store as a bill collector.” Her husband died on the battlefield and her son in the atomic bombing. Her left fingers were stuck together from burns she suffered in the bombing. She would wear long-sleeves even in the middle of summer to hide the keloid scars on her arms. Many of the newspaper carriers were children who had lost fathers living in a dormitory for mothers with dependent children.

Mr. Nagatsu left Hiroshima to get a job after graduation from high school. Afterward, starting in 1969, construction of high-rise apartment buildings in the Motomachi district went into full swing, taking about 10 years to tear down old houses, create a central park, and carry out embankment work on the riverside area. When he returned to Hiroshima in 1994, the town had changed completely.

Around that time, Mr. Nagatsu, who is also a poet, shook off the “feelings of guilt of not experiencing the atomic bombing” and started to write accounts about his days in the area of Motomachi. A woman bill collector often appeared in his writings as a motif. “Someone has to leave records of Motomachi,” he explained. Mr. Nagatsu now lives in his parents’ home in Iwakuni City but continues to adhere to that idea.

Koreans suffered discrimination in addition to hardships as A-bomb survivors

“I think that there were many more people from the Korean Peninsula in Hiroshima than generally known.” Kwon Joon-oh, 72, vice chair of the Committee Seeking Measures for the Korean A-bomb Victims, lived in Motomachi until 1960. He recalls, “People relied on their families for support. It was not unusual for two or three families to live under one roof.”

Although still a child, he saw and heard about the hard lives of the people around him. “Koreans faced severe discrimination. They had to hide not only being an A-bomb survivor but also their homeland just to find a job.” Some had nowhere to go and became addicted to alcohol. “Even after the war, Koreans had to fight hard to live their lives.”

Some people miss the squalid energy behind poverty with nostalgia. “I started to think that way when I was about 40.” Seiroku Nango, 72, of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, drew from memory a map of Motomachi Hondori, a main shopping street that ran through the district from north to south. Among the more than 40 stores on the map were an ice cream shop, which had served as a movie set, and a cafeteria at which Mr. Nango watched a broadcast of the wedding parade of the now-retired emperor and empress. He said many of those building were illegally constructed.

There were day-to-day problems in the residential area that could not be whitewashed, such as roadside robberies. When Mr. Nango’s family moved out of the district in 1964 as his family rice-cake shop business finally started becoming successful, he felt as if he “never wanted to return.”

His feelings changed more than 20 years later when he was walking along a nearby river. The moment he sensed “the same fishy smell of the river as before,” memories of the town mixed with lives of all kinds in the gap between the atomic bombing and the reconstruction came back to him tinted by nostalgia.

“I now feel I don’t want to forget.” That idea is imbued in the title of the map “Ushinawareta Motomachi wo Motomete” (in search of the lost Motomachi, in English) in hopes that that the memories of the town that most certainly existed would be recorded in some way.

(Originally published on July 16, 2021)