Striving to fill voids, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing — “Shichotai” remnants, Part 5: Site of soccer stadium

Jul. 18, 2021

Should be made into place where lives of victims are remembered

Citizens begin movement to pass on memories

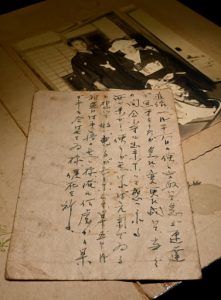

One letter postmarked August 5, 1945, is kept in the archives of the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. The postcard was written by Tamotsu Nakagawa, then 28, and addressed to his wife Yoshiko. Mr. Nakagawa belonged to the former Japanese Army’s transport unit known as the Chugoku District transport soldier recruitment unit (“Shichotai” in Japanese). Mr. Nakagawa wrote about, among other things, his feelings toward their daughter Keiko, who had died of an illness at the age of 3 earlier in March.

“You know that I am well if you do not hear from me. Five months have already passed since Keiko died. Make sure you attend to all the details of her first ‘Bon’ memorial service. I will pray for her soul wherever I am. I hope you are well,” were some of the sentiments expressed in his writing.

It is believed that Mr. Nakagawa experienced the atomic bombing near his barracks on the day after he posted this letter. He died four days later at the place he was taken for treatment. Mr. Nakagawa, a company employee, was living in Tokyo with his wife and two children before he was drafted in March 1945. He was first assigned to an army unit in Tottori Prefecture, his legally recognized domicile, and then was transferred to Hiroshima.

One month after Mr. Nakagawa died in the atomic bombing, the letter reached Yoshiko and their son Shinobu, then 1, in Tottori Prefecture, where they had been evacuated for safety’s sake. Shinobu, now 76, lives in Tokyo’s Shinagawa Ward. “I have no memory of my father, so the letter is a miraculous keepsake that conveys his thoughts right before his death. I hope keeping it as evidence that he lived in this world can serve for the repose of his soul.” The letter was handed down to Shinobu when his mother died in 2014. He donated it to the memorial hall in 2018.

No monument or explanatory panel

As an architect, Shinobu used to run a design firm. Since closing the firm in 2016, he has been able to afford the time to explore his father’s life. In a letter to Yoshiko, his father had written, “Only after I became a father did I truly learn to appreciate how much I owe to my parents and how adorable our children are,” and “I had hoped to see Shinobu again, but I couldn’t….” Learning of his father’s love for his children, Shinobu said his chest tightened with emotion.

He visited Hiroshima to find out more about his father. He discovered the temple at which his mother received the box containing his father’s ashes. Nevertheless, there are still “voids” to fill. There is no definite information about what his father did in the Shichotai unit and where he was when the bomb exploded. Shinobu walked around the open space of Hiroshima’s Central Park, the location where the facilities of the unit were once located, but he was unable to find any monument for A-bomb victims or explanatory panels telling of the detailed circumstances around the time of the atomic bombing.

For this reason, although he lives in Tokyo, he is intensely interested in what will happen to the remnants of the unit’s facilities. “I plan to visit there as soon as the coronavirus pandemic is under control.” While the city government is considering preserving a portion of the remnants in the park, as an architect, Shinobu is interested in how the soccer stadium and the remnants will be made to share the same space. “There are many souls of victims under the ground of Central Park. I hope it can be made into a place where visitors also have the opportunity to face this tragic history,” he said.

Some citizens have begun to utilize the remnants in passing down memories of the atomic bombing. On July 15, eight Hiroshima Peace Volunteers from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum participated in a fieldwork event near the excavation site to learn what they could about the Shichotai unit. Shunsuke Taga, 71, who organized the event, served as a guide.

Hope for preservation of part of remnants

Mr. Taga referred to how the Shichotai unit’s members were looked down on in the army because they transported supplies behind the lines to the combat troops. Some sang the ditty, “If transport soldiers can be called soldiers, butterflies and dragonflies can be called birds.” Notes and testimonies made by former transport soldiers tell of the unjust treatment. “I was told that horses were more important than I was, and I was actually beaten,” describes one account.

On the other hand, many civilians from inside and outside Hiroshima Prefecture were recruited and assigned to work for the Shichotai unit to help in the war effort. Many were killed in the atomic bombing. Mr. Taga said, “Even one part of the remnants should be preserved to convey the overall image of Hiroshima as a military city and the horrific reality of war.”

The remnants of the Shichotai unit’s facilities were discovered prior to construction of a soccer stadium. The remnants silently tell everyone that what happened there should not be forgotten into a “void,” even if the cityscape should happen to change.

While reporting for this article, we met victims’ relatives who are trying to hand down records of victims’ lives and personal belongings. We listened to elderly former members of the unit and discovered written notes. We can still preserve “evidence” to fill the voids that persist in the overall picture of the atomic bombing, the military city, and the history of its reconstruction.

(Originally published on July 18, 2021)