Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 76 years after the atomic bombing—Records of First Girls’ School mobilized students, Part 2: Daily records describe grueling work

Jul. 20, 2021

Four shifts, making artillery shells — “Like a military organization”

Some students lost their lives doing work

Starting in the spring of 1944, school students were mobilized to work all year round. Throughout Japan, third- and fourth-year students at junior high schools and girls’ high schools were sent to military supply factories. The number of such students continued to increase rapidly at that time.

Yachiyo Kato (née Tominaga), 92, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, was a fourth-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (First Girls’ School; now Funairi High School) when she was mobilized to work at the Nishikaniya factory of Japan Steel Works (now in Minami Ward) in November 1944. “I guess it was easy to mobilize students because there was a clear chain of command. It was as if the school had become a military organization,” said Ms. Kato.

‘Prepared to lay down lives’

A patriotic student corps was organized under the supervision of educators. Students were divided into small groups and made to work in accordance with four six-hour shifts: Morning, day, night and dawn shifts. The only day off was the first Monday of each month when factory operations were suspended due to electricity conservation efforts during the war.

In March the following year, about 250 new third-year students were added to the corps. It is estimated that about 650 of the school’s students were working when the war ended.

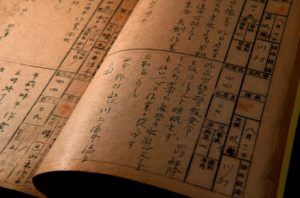

For girls between 14 and 17, making artillery shells using unfamiliar machines entailed the risk of injury. Records of their work are still archived at Funairi High School. Entries indicate such situations as: “A piece of metal flew into the left eye, injuring the cornea. Taken to medical office,” or “At 6:00 p.m., was injured using a lathe. Nail of right-hand finger sliced off.”

Teachers tried to boost the morale of the students when news indicated the Japanese troops at the front were in a predicament. “Just like the soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army, we should push ahead while being prepared to lay down our lives.” This entry in the daily records was made on July 19, 1944, when news arrived that Japanese forces had suffered a crushing defeat on the island of Saipan.

Around the same time, one fourth-year student died of appendicitis shortly after returning to her home after a night shift. Did this happen because she continued working despite the pain? Other students died at different factories, with reports of five deaths addressed to the mayor of Hiroshima and others.

Horrific working conditions

First Girls’ School sent its students to the Kure Naval Arsenal and four factories in the city of Hiroshima, including Japan Steel Works. The worst workplace among them was a military uniform factory in the town of Funairikawaguchi-cho (now part of Naka Ward). “A rumor was going around that workers at the factory were inconsiderate and heartless, and the teachers were worried about that,” said Ms. Kato.

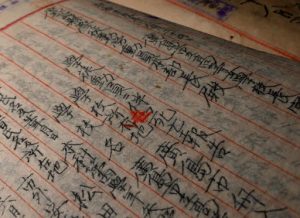

A report on the status of mobilized students has entries that lend support to her description. Forty-seven students were made to work continuously for nine-and-a-half hours, starting at 7:30 in the morning. The report indicates, “There are several extremely deplorable issues such as the treatment of students,” and “Many complaints among students. Need to pay more consideration.” The report also conveys the information that workers insulted students. They were told, “It’s better not to have mobilized students,” or “You good-for-nothing.”

Teachers held talks with factory representatives, but conditions did not improve at all. Day by day, the number of absentee students increased. In March 1945, the school stopped sending its students to the factory. They were instead made to work in different factories.

One of the students was Takako Shimooka, Ms. Kato’s classmate. The daily record reveals the reasons why she was absent or felt ill. When she graduated, the high school arranged for her to work at the prefectural government offices in the area of Kako-machi (now Kako-machi in Naka Ward) as a member of a corps of women volunteer workers. She should have been liberated from the harsh labor. But one month after she turned 17, she was 900 meters from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing on August 6. Ms. Shimooka was the younger sister of this reporter’s grandmother.

Along Peace Boulevard, there is a monument for the students and teachers at the girls’ school. The names of 676 victims are engraved on a nearby panel. My grandaunt’s name is absent, even though she was a student at the school until only four months before the bombing. Her remains have never been found.

(Originally published on July 20, 2021)