Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing: Sealed, charred documents of Ms. Kato, former “94 Zaimoku-cho” resident, donated to museum

Aug. 4, 2021

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

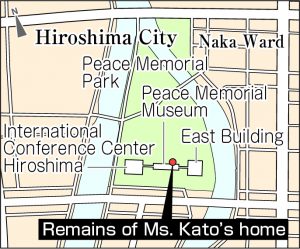

Asa Kato, a victim of the atomic bombing who was 66 years old at the time, lived at “94 Zaimoku-cho,” which is now located around the site of the main building of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in Peace Memorial Park (in the city’s Naka Ward). Ms. Kato’s family donated her belongings, including charred documents and an official seal, to the museum. The artifacts serve as evidence showing people used to live in the part of the city that surrounds the A-bombing hypocenter. According to a museum spokesperson, “The materials are valuable for learning about people’s lives and the damage caused by the atomic bombing in the area where the museum is now located.”

Sumihisa, 78, the grandson of Asa who is a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, inherited from his now deceased parents the artifacts removed from the safe found in the ruins of Asa’s home. Among the artifacts were an official seal with the name “Kato” carved on it, charred documents and a property title deed, a coin purse with a metal clasp, keys, and a lunch box with coins in it. Sumihisa donated the articles to the museum earlier in April this year in the hopes of preserving them for the sake of future generations.

The address of 94 Zaimoku-cho, where Ms. Kato lived, was located on a street corner in the area of Zaimoku-cho, where shops, restaurants, and medical clinics stood side by side. In their dimensions, the houses lined in this way were deep but not wide.

“I heard the story that she had rented out the space facing the street to a vegetable and fruit shop and lived alone in the back room,” Sumihisa said. Asa and her husband, Moichi, were evacuated from the city for a time, but she returned to Zaimoku-cho, where she lived for a long time after Moichi had died first, in January 1945.

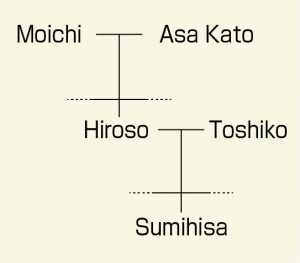

On August 6, 1945, the date of the atomic bombing, Zaimoku-cho, Nakajima-honmachi, and other towns in the Nakajima district, which now comprise present-day Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, were wiped out by the atomic bomb detonated in the sky directly above the area. Sumihisa’s father, Hiroso, a police officer who was stationed at a police station in Otake City, engaged in relief operations, forcing his wife Toshiko to leave Otake City with the two-year-old Sumihisa to look for Asa in the ruins of her home in Zaimoku-cho. They were unable to find Asa’s remains.

“We picked up ashes in the ruins of the house that looked like the bones from a dog and placed the bones in her grave as if they belonged to my grandmother.” Sumihisa heard this story from his father later, because he was too small to have any memory of that time. While he was alive, Hiroso took pains to save the items because, he said, “They are important.”

During 2015–2017, the city conducted excavations beneath the museum’s main building prior to installing a seismic isolator underground to fortify the building in the event of an earthquake. Sadaichi Yamagata, 51 at the time of the bombing, was Ms. Kato’s next-door neighbor to the south at a residence with the address “95 Zaimoku-cho.” He ran a cutlery shop but was killed in the bombing. Unearthed from the ground surface of the ruins of his home was a collection of charred wooden rice scoops. The city government cut out and removed a portion of the ground surface, which is now preserved in the memorial museum. Sadaichi is the great-grandfather of Ryota Yamagata, a track and field athlete taking part in the Tokyo Olympic Games now being held.

The museum’s curator Mari Shimomura said about the items donated by Ms. Kato’s family and the artifacts unearthed from Sadaichi’s home, “They are valuable because we have few materials related to the Nakajima district. The more we have as evidence of the lives of each household, the closer we can come to understanding the situation at the time.” Sumihisa, a former city hall employee who has experience in organizing the annual Peace Memorial Ceremony, said, “I hope the artifacts can help in some way to convey that the present-day Peace Memorial Park used to be a neighborhood.”

(Originally published on August 4, 2021)

Ms. Kato’s family hopes artifacts help future generations learn of lives at hypocenter

Asa Kato, a victim of the atomic bombing who was 66 years old at the time, lived at “94 Zaimoku-cho,” which is now located around the site of the main building of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in Peace Memorial Park (in the city’s Naka Ward). Ms. Kato’s family donated her belongings, including charred documents and an official seal, to the museum. The artifacts serve as evidence showing people used to live in the part of the city that surrounds the A-bombing hypocenter. According to a museum spokesperson, “The materials are valuable for learning about people’s lives and the damage caused by the atomic bombing in the area where the museum is now located.”

Sumihisa, 78, the grandson of Asa who is a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, inherited from his now deceased parents the artifacts removed from the safe found in the ruins of Asa’s home. Among the artifacts were an official seal with the name “Kato” carved on it, charred documents and a property title deed, a coin purse with a metal clasp, keys, and a lunch box with coins in it. Sumihisa donated the articles to the museum earlier in April this year in the hopes of preserving them for the sake of future generations.

The address of 94 Zaimoku-cho, where Ms. Kato lived, was located on a street corner in the area of Zaimoku-cho, where shops, restaurants, and medical clinics stood side by side. In their dimensions, the houses lined in this way were deep but not wide.

“I heard the story that she had rented out the space facing the street to a vegetable and fruit shop and lived alone in the back room,” Sumihisa said. Asa and her husband, Moichi, were evacuated from the city for a time, but she returned to Zaimoku-cho, where she lived for a long time after Moichi had died first, in January 1945.

On August 6, 1945, the date of the atomic bombing, Zaimoku-cho, Nakajima-honmachi, and other towns in the Nakajima district, which now comprise present-day Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, were wiped out by the atomic bomb detonated in the sky directly above the area. Sumihisa’s father, Hiroso, a police officer who was stationed at a police station in Otake City, engaged in relief operations, forcing his wife Toshiko to leave Otake City with the two-year-old Sumihisa to look for Asa in the ruins of her home in Zaimoku-cho. They were unable to find Asa’s remains.

“We picked up ashes in the ruins of the house that looked like the bones from a dog and placed the bones in her grave as if they belonged to my grandmother.” Sumihisa heard this story from his father later, because he was too small to have any memory of that time. While he was alive, Hiroso took pains to save the items because, he said, “They are important.”

During 2015–2017, the city conducted excavations beneath the museum’s main building prior to installing a seismic isolator underground to fortify the building in the event of an earthquake. Sadaichi Yamagata, 51 at the time of the bombing, was Ms. Kato’s next-door neighbor to the south at a residence with the address “95 Zaimoku-cho.” He ran a cutlery shop but was killed in the bombing. Unearthed from the ground surface of the ruins of his home was a collection of charred wooden rice scoops. The city government cut out and removed a portion of the ground surface, which is now preserved in the memorial museum. Sadaichi is the great-grandfather of Ryota Yamagata, a track and field athlete taking part in the Tokyo Olympic Games now being held.

The museum’s curator Mari Shimomura said about the items donated by Ms. Kato’s family and the artifacts unearthed from Sadaichi’s home, “They are valuable because we have few materials related to the Nakajima district. The more we have as evidence of the lives of each household, the closer we can come to understanding the situation at the time.” Sumihisa, a former city hall employee who has experience in organizing the annual Peace Memorial Ceremony, said, “I hope the artifacts can help in some way to convey that the present-day Peace Memorial Park used to be a neighborhood.”

(Originally published on August 4, 2021)