Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing—Medical charts in aftermath, Part 1: Records from Ninoshima Island

Jul. 30, 2021

Army doctor recorded victim’s “last moments” and actual date of death in autopsy report

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

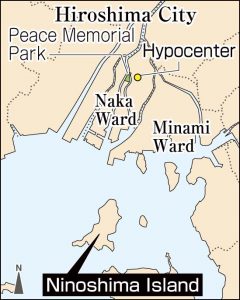

A quarantine facility on Ninoshima Island, located in Hiroshima Bay in the city’s Minami Ward, was turned into a temporary field hospital after the atomic bombing by the U.S. military. About 10,000 wounded people were transported to the hospital during a period of 20 days starting on August 6, 1945. Amid the chaos, few medical materials recording each patient’s wounds and diseases were left behind.

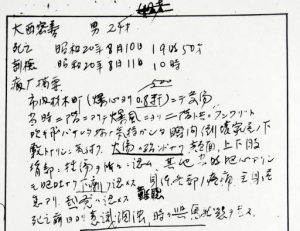

However, the Hiroshima University Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM), in the city’s Minami Ward, has enough materials to fill a small number of the voids in information. They constitute pathological autopsy reports of 12 victims written during August 10–15 by the late army physician Kiyoshi Yamashina in what became known as the “Yamashina Report.”

Dr. Yamashina arrived in Hiroshima to conduct a survey

The day after the atomic bombing, Japan’s Ministry of War ordered Dr. Yamashina in Tokyo to conduct a survey of Hiroshima. In his notes, he wrote: “All they said was that a single special bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, killing and injuring 130,000 people in an instant, and that I should carry a gas mask because the kind of weapon was unknown.” On August 8, Dr. Yamashina flew to Hiroshima as a member of the ministry’s survey team.

On the morning of August 10, he cut open the body of a 13-year-old boy on Ninoshima Island, which is believed to be the first pathological autopsy case to clarify the impact of the bombing on the human body. He conducted autopsies on the bodies of 12 people. For most, the direct causes of death were burns and external injuries, and the effects of radiation on the bone marrow were also recorded. After the war ended, the U.S. military requested that Dr. Yamashina submit his medical records, which they had translated into English to take back to United States.

After the war, Dr. Yamashina donated his original records to Hiroshima University. In 1973, the English materials were returned to Japan from the United States as one of the “materials returned by the U.S. military.” The information was archived at Hiroshima University, and with that, the original records of Dr. Yamashina also gained prominence.

For the story, I again turned over reports of the records. The description of “Mitsuzen Onishi,” whose date of death was listed August 10, caught my attention. The interview conducted just before he died indicated he had experienced the atomic bombing in “Zaimoku-cho,” a district close to the hypocenter that was destroyed in the bombing and is now a part of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the city’s Naka Ward.

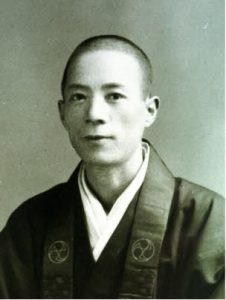

As the information rang a bell, I opened a Chugoku Shimbun newspaper from 2000, in which was printed a feature article titled “Record of Hiroshima: Photographs of the Dead Speak,” which traced the lives of victims who lived in Zaimoku-cho. There was a person in the article with the same name but with one of the kanji characters different. The man described in the article was the chief priest of Anrakuin Temple, a popular temple for those praying for easy childbirth. His wife and three children, aged between five months and 12 years, were also killed in the atomic bombing. The article mentioned that this Mitsuzen Onishi had also died on Ninoshima Island.

Family had no choice but to engrave gravestone with “August 6” as date of death

“I never imagined such documentation existed.” Shigeko Onishi, 82, Kure City, expressed surprise when she saw the records. Shigeko is the wife of Mr. Onishi’s oldest son Yoshio, who died in 2003 at the age of 67 and escaped death at the time of the atomic bombing because he had evacuated in a group of schoolchildren to the countryside.

In 1955, 10 years after the atomic bombing, the family learned that Mr. Onishi’s ashes had been buried within the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, revealing that he had died on Ninoshima Island. Besides that detail, his family had no other information. They were forced to engrave the family gravestone, located in Kure City, with “August 6, 1945” as the date of death. According to the records, however, he actually died on August 10. The records detail the damage he suffered from the atomic bombing: “Contusions on face, upper and lower limbs, and back”; “Clouding of consciousness starting the day before he died,” were listed.

“I wish I could have shown this to my husband. He would have been pleased to know about the last moments of the father who loved him,” as Shigeko interpreted the situation, even though the description was painful to read. Her conclusion resulted from the knowledge that Yoshio had been trying to leave evidence of his family while he was alive.

Anrakuin Temple vanished in the atomic bombing. Yoshio, who was supposed to succeed his father’s temple position, worked for an electric power company after the war. Four years before his death, Yoshio entrusted to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum a letter from that had been sent to him by his father a month before the bombing. “We might be separated physically, but let’s make sure we stay together emotionally.” It was heart-wrenching for this reporter to consider the caring words for his family alongside the Yamashina Report.

There remain points of ambiguity in the Yamashina Report. It indicates that Mr. Onishi experienced the bombing inside a structure in Zaimoku-cho. However, the family heard from a former neighbor that he was observed leaving the temple, in a different location, shortly before the bombing. Unclear is whether he returned to the temple to retrieve something, or if the report is simply incorrect. I tried to talk to Yoshio’s sister to find out more, but we failed to meet because she was in poor health.

Medical records are evidence by which the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons is revealed. We will approach the hidden truth by connecting A-bomb survivor testimonies with other materials, while considering the challenges presented in preserving and utilizing such records.

(Originally published on July 30, 2021)