Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing—Medical charts in aftermath, Part 3: Unavailable to public

Aug. 1, 2021

Even family members not allowed access to medical records

Documents should be utilized to convey suffering

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

On the website of the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives is a list of 266 items donated by Hitoshi Takayama, who served as chairman of the Higashihiroshima City Association of Atomic Bomb Sufferers before he died at 89 in 2020.

The listed items 1 through 218, which comprise medical charts of atomic bomb survivors, are labeled as being “Unavailable to the public.” They represent copies of the medical records of 218 survivors written by physicians at the Hiroshima Sanatorium for Wounded Soldiers, which was located in the town of Saijo (now part of Higashihiroshima City) between August 6 and December 20, 1945.

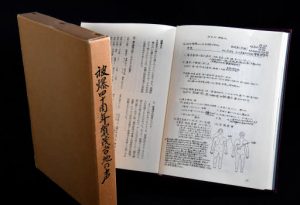

Mr. Takayama received the copies from the sanatorium’s successor organization, the National Sanatorium Hiroshima Hospital (now the Higashihiroshima Medical Center), as he was compiling accounts of local A-bomb survivors for the 1986 publication Forty years after the atomic bombing: Voices of Kamo-daichi Plateau (Hibaku 40-shunen Kamo Daichi no Koe, in Japanese). The information represents a detailed record of site and extent of patient injuries, loss of appetite, symptoms such as the start of hair loss, and details about medical treatments.

Mr. Takayama included one patient’s records in the publication without disclosing the patient’s name. “We should treat these records as the basis for pursuing peace provided by the person who lingered on the brink of death due to the atomic bombing and learn from them,” Mr. Takayama wrote.

Whereabouts of originals unknown

The medical record copies were donated in 2002. According to the Higashihiroshima Medical Center, the whereabouts of the originals are unknown. The copies are all the more precious as proof of the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons, which is clearly illustrated by the death of a boy believed to be one of the 218 patients based on accounts written by those concerned.

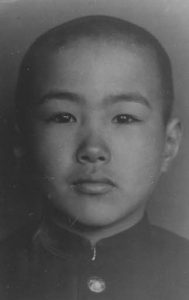

Takeshi Yoshitomi was 12 years old and a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School in the city’s Naka Ward). He did well at school. His father was the director of the dispensary of the sanatorium, nearby which his family lived in an official residence.

On August 6, 1945, the date of the atomic bombing, Takeshi was in the school building around 900 meters from the hypocenter. He escaped from under the collapsed structure and arrived home before dawn the next day, August 7. “I heard that he was well at first and tended potatoes in the field and fed chickens,” said Mutsuko Yoshitomi, 77. Ms. Yoshitomi said she heard this from her husband Yasushi, who was Takeshi’s younger brother, before Yasushi’s death at the age of 77 in 2013. Ms. Yoshitomi lives in Akashi City, Hyogo Prefecture.

But Takeshi soon became ill. Two weeks after the atomic bombing, he began to run a high fever and had to stay in bed. A note written by a physician at the hospital indicated that his white blood cell count had dropped sharply to 300, compared with a normal count of between 4,000 and 8,000. Despite being given blood transfusions and other treatments, Takeshi died on August 27.

After her husband died, Ms. Yoshitomi began to attend the annual memorial ceremony for the junior high school as a representative for a group of Takeshi’s relatives. She has indicated that if there are detailed medical records of the effects of the radiation from the bombing on her late brother-in-law’s health, that information should be “utilized.” “Let the records speak to the horror of the weapons, which is different from that of conventional weapons,” she said.

This reporter requested the prefectural archives to disclose Takeshi’s medical records based on the wishes of his sister-in-law. The organization responded, however, that it would not release the records even to his relatives let alone to a member of the media.

Disclosure would be considered if request came directly from patient

According to staff at the prefectural archives, use of personal information listed in the medical records will be restricted until an appropriate time more than 110 years after the records were first made or obtained, based on standards set by the prefectural government. Other materials falling under the same category include materials related to criminal records and serious hereditary diseases. Mikio Kinoshita, director of the prefectural archives, explained, “Even though hereditary effects are still unclear, the potential for discrimination against second-generation survivors must be taken into consideration.”

This reporter conveyed the information that Takeshi did not have children. But the prefectural archives staff responded that, “The entirety of the records are unavailable to the public, and therefore we wouldn’t be able to disclose just a part of them.” In the past, some records were disclosed with the patients’ names withheld in special cases for research, but that is not possible anymore. If a request is made directly by the person him or herself, the archives would consider disclosing the information based on the same standards put in place by the prefecture.

Based on information in the aforementioned publication Voices of Kamo-daichi Plateau, 46 victims among the A-bomb survivors whose conditions were recorded in the medical chart information died in the sanatorium. Others recovered and were discharged. After such a long time, how many are still alive and well? If the records were only to be directly disclosed to the people themselves, the materials would slowly be lost over time.

Medical records such as the charts created at the Hiroshima Sanatorium for Wounded Soldiers will become even more important, because it will become more and more difficult to hear the stories directly from those who suffered from the A-bomb’s thermal rays, blast, and radiation. Such records should be used for passing on memories of the bombing within families and conveying the inhumanity of nuclear weapons while keeping names of patients confidential.

(Originally published on August 1, 2021)