Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing—Medical charts in aftermath, Part 4: Records of 75 people

Aug. 2, 2021

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

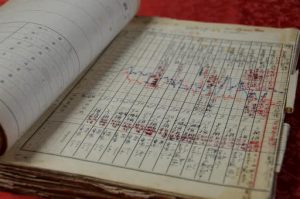

When the lid of the wooden box was removed, there appeared a file of papers labeled “A-bomb documents, Department of Internal Medicine, Showa Fiscal 20 [1945]” written in bold, ink characters. The file contained the medical charts of 75 individuals who experienced the atomic bombings in Hiroshima or Nagasaki. The Saga Prefectural Medical Center Koseikan (former Saga Prefectural Hospital), located in Saga City in Saga Prefecture, Kyushu, continues to hold on to the records. Therein, the course of diagnoses and treatments provided to the survivors during a period of six months after the atomic bombings are recorded.

In March 2011, the 229 pages of medical charts were discovered in an old locker of the Koseikan medical center’s department of internal medicine. In the middle of organizing documents in conjunction with the replacement of a head nurse, the newly appointed person in the position happened upon them. Ryutaro Maeyama, 87, former head of the neurosurgery department at the Koseikan medical center, explained his surprise at the discovery. “When I saw the medical charts for the first time, I was amazed they had been kept so long,” he said. Mr. Maeyama was also involved in analysis of the records.

Records escaped collection by U.S. military

During Japan’s postwar Occupation period, the U.S. military collected a vast amount of medical documentation related to the A-bomb survivors and took it back to America. The Koseikan medical center has documents in its archives describing how it was visited numerous times by U.S. Occupation Forces. Mr. Maeyama surmised that, “Someone could have hidden the charts to make sure they wouldn’t be taken away.”

The medical chart dates begin August 14, 1945, one day prior to the official end of World War II, and end with the date January 5, 1946. The charts are of 75 people who experienced the atomic bombing in Nagasaki or Hiroshima, where they had stayed for work or student mobilization, fled to their hometown, and sought treatment at the Koseikan medical center. The medical charts contain records of each of the individual’s condition at the time of the bombing, symptoms, results of blood tests, and details of medical treatments provided for them. Seven of the people experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. From the medical charts, the death of one 57-year-old woman could be confirmed.

The chart of the deceased woman reads, “As soon as the bomb was dropped, she was trapped under a collapsed house, but she managed to stand up on her own and flee.” It continues: “She came back to Saga in the evening of August 8.” She apparently developed a fever and diarrhea and consulted a physician on September 13, at which time she was hospitalized. She was prescribed vitamins, glucose, and heart stimulants, but her condition grew worse with symptoms described as swollen legs, general swelling, and so on. On October 2, the chart indicates, “Deceased, discharged from hospital.”

Mr. Maeyama said, “Through these records, we can understand that the hospital staff did everything they could do for the patient.” Because the Koseikan medical center had survived the air raids on Saga City that started the night of August 5, it maintained sufficient stocks of medicines and other supplies. The physicians sought alternative treatment options such as transfusion of blood from relatives, as well as performed autopsies. Starting in September, more and more outpatients wanted to undergo blood testing, a situation that paints a picture of the circumstances at that time, marked by anxiety that had spread among citizens due to increasing awareness of radiation’s health effects.

The medical charts were analyzed by members of the Saga Medical History Research Group, which consists of physicians and researchers including Mr. Maeyama. The group would gather at Mr. Maeyama’s home and analyze the records written in both Japanese and German. It took the members about three years to complete the work.

Records organized for analysis

In the course of the work, Odai Akasaka, 34, a public relations staff member at the Koseikan medical center, played an important role. A licensed curator, Mr. Akasaka had just moved to his new job at the Koseikan medical center from a historical museum located in a neighboring city. He immediately volunteered to support the group’s activities, and worked even during his free time on organizing the documents.

The medical charts were dusty and out of sequence. Mr. Akasaka checked patient names on the charts one by one, assigned a number to each of them, and rearranged the information. For purposes of preservation and analysis, digital images were taken of the charts. Giving credit where it was due, Mr. Maeyama said, “We were able to complete the analysis because Mr. Akasaka helped organize the records. The work bore fruit thanks to the enormous amount of energy he spent on the project.”

Looking back on in the work of organizing the medical charts, Mr. Akasaka said, “The patients barely escaped alive and returned to Saga, only to die from diseases related to the atomic bombings. I considered it my mission to convey that history.”

Nevertheless, the hospital’s archives room, where the medical charts are now kept, lacks the appropriate temperature and humidity controls that are typically found museums. As the documents include significant amounts of personal information, the question of how to use them presents a real challenge.

After completion of analysis of the medical charts, the research group held a public debriefing session in Saga City in 2015. Nagasaki University displayed the charts without revealing the contents. Since that time, the charts have not been shown publicly. Mr. Akasaka said, “We don’t want to finish our efforts by simply reporting that the materials have been archived.” How can historical materials be passed on to future generations? How can they be utilized? Effective answers to these questions have yet to be proposed.

(Originally published on August 2, 2021)

Survivors returned home to Saga from A-bombed cities

Hospital protects medical charts indicating course of struggles

When the lid of the wooden box was removed, there appeared a file of papers labeled “A-bomb documents, Department of Internal Medicine, Showa Fiscal 20 [1945]” written in bold, ink characters. The file contained the medical charts of 75 individuals who experienced the atomic bombings in Hiroshima or Nagasaki. The Saga Prefectural Medical Center Koseikan (former Saga Prefectural Hospital), located in Saga City in Saga Prefecture, Kyushu, continues to hold on to the records. Therein, the course of diagnoses and treatments provided to the survivors during a period of six months after the atomic bombings are recorded.

In March 2011, the 229 pages of medical charts were discovered in an old locker of the Koseikan medical center’s department of internal medicine. In the middle of organizing documents in conjunction with the replacement of a head nurse, the newly appointed person in the position happened upon them. Ryutaro Maeyama, 87, former head of the neurosurgery department at the Koseikan medical center, explained his surprise at the discovery. “When I saw the medical charts for the first time, I was amazed they had been kept so long,” he said. Mr. Maeyama was also involved in analysis of the records.

Records escaped collection by U.S. military

During Japan’s postwar Occupation period, the U.S. military collected a vast amount of medical documentation related to the A-bomb survivors and took it back to America. The Koseikan medical center has documents in its archives describing how it was visited numerous times by U.S. Occupation Forces. Mr. Maeyama surmised that, “Someone could have hidden the charts to make sure they wouldn’t be taken away.”

The medical chart dates begin August 14, 1945, one day prior to the official end of World War II, and end with the date January 5, 1946. The charts are of 75 people who experienced the atomic bombing in Nagasaki or Hiroshima, where they had stayed for work or student mobilization, fled to their hometown, and sought treatment at the Koseikan medical center. The medical charts contain records of each of the individual’s condition at the time of the bombing, symptoms, results of blood tests, and details of medical treatments provided for them. Seven of the people experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. From the medical charts, the death of one 57-year-old woman could be confirmed.

The chart of the deceased woman reads, “As soon as the bomb was dropped, she was trapped under a collapsed house, but she managed to stand up on her own and flee.” It continues: “She came back to Saga in the evening of August 8.” She apparently developed a fever and diarrhea and consulted a physician on September 13, at which time she was hospitalized. She was prescribed vitamins, glucose, and heart stimulants, but her condition grew worse with symptoms described as swollen legs, general swelling, and so on. On October 2, the chart indicates, “Deceased, discharged from hospital.”

Mr. Maeyama said, “Through these records, we can understand that the hospital staff did everything they could do for the patient.” Because the Koseikan medical center had survived the air raids on Saga City that started the night of August 5, it maintained sufficient stocks of medicines and other supplies. The physicians sought alternative treatment options such as transfusion of blood from relatives, as well as performed autopsies. Starting in September, more and more outpatients wanted to undergo blood testing, a situation that paints a picture of the circumstances at that time, marked by anxiety that had spread among citizens due to increasing awareness of radiation’s health effects.

The medical charts were analyzed by members of the Saga Medical History Research Group, which consists of physicians and researchers including Mr. Maeyama. The group would gather at Mr. Maeyama’s home and analyze the records written in both Japanese and German. It took the members about three years to complete the work.

Records organized for analysis

In the course of the work, Odai Akasaka, 34, a public relations staff member at the Koseikan medical center, played an important role. A licensed curator, Mr. Akasaka had just moved to his new job at the Koseikan medical center from a historical museum located in a neighboring city. He immediately volunteered to support the group’s activities, and worked even during his free time on organizing the documents.

The medical charts were dusty and out of sequence. Mr. Akasaka checked patient names on the charts one by one, assigned a number to each of them, and rearranged the information. For purposes of preservation and analysis, digital images were taken of the charts. Giving credit where it was due, Mr. Maeyama said, “We were able to complete the analysis because Mr. Akasaka helped organize the records. The work bore fruit thanks to the enormous amount of energy he spent on the project.”

Looking back on in the work of organizing the medical charts, Mr. Akasaka said, “The patients barely escaped alive and returned to Saga, only to die from diseases related to the atomic bombings. I considered it my mission to convey that history.”

Nevertheless, the hospital’s archives room, where the medical charts are now kept, lacks the appropriate temperature and humidity controls that are typically found museums. As the documents include significant amounts of personal information, the question of how to use them presents a real challenge.

After completion of analysis of the medical charts, the research group held a public debriefing session in Saga City in 2015. Nagasaki University displayed the charts without revealing the contents. Since that time, the charts have not been shown publicly. Mr. Akasaka said, “We don’t want to finish our efforts by simply reporting that the materials have been archived.” How can historical materials be passed on to future generations? How can they be utilized? Effective answers to these questions have yet to be proposed.

(Originally published on August 2, 2021)