Survivors’ Stories: Satoko Sasaguchi, 90, Hiroshima—Conductor on “first streetcar” to run in aftermath of A-bombing

Aug. 25, 2021

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

One streetcar ran through Hiroshima on August 9, three days after the city had been reduced to ruins in the atomic bombing. The story continues to be told of how it was called “the first streetcar” to run in the aftermath of the bombing and served as a symbol of the city’s recovery. Satoko Sasaguchi (née Oka), 90, a member of the streetcar crew, was 14 years old at the time. Amid the chaos, she poured her soul into her work as conductor of the streetcar.

Ms. Sasaguchi was born and raised in present-day Oda City, in Shimane Prefecture. In the summer of 1944, she moved to Hiroshima City, longing for “the city” she had heard about from Kikuko, her older sister by two years who went to the Hiroshima Electric Railway Girls’ School, located in Hiroshima’s Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward). “I was overwhelmed by the buildings all lined up in rows and streetcars running through the city,” Ms. Sasaguchi said as she reminisced about that time.

She lived in the home of her sister’s homeroom teacher and went to Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School) while engaged in work at a munitions factory. The next spring, she finally was able to get into the Electric Railway Girls’ School, but had almost no chance to take classes because of World War II. She underwent only one week of training for streetcar conductor operations, during which she made desperate efforts to memorize the names of streetcar stops and phrases frequently used by conductors, such as “Does everyone have a ticket?” before she started the job.

On August 6, 1945, she was scheduled to work the afternoon shift. She was about to have breakfast at the dormitory adjacent to the school, around two kilometers from the hypocenter, when a “bluish-white light suddenly spread outside the window.” She had lost consciousness and, when awakened by pain in her lower back, found herself buried under rubble.

She crawled out from the wreckage toward light and went outside in a panic. The schoolyard was crowded with wounded girl students, whose screams were audible. Ms. Sasaguchi returned to her room in the dorm, quickly put on an air-raid hood, and headed in the direction of the Ujina area with a first-aid kit. She said smoke was coming out from under her hood, possibly due to the thermal rays from the atomic bomb.

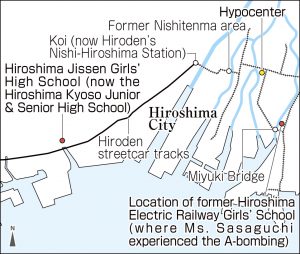

She fled temporarily to Kanda Shrine (now in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward), then walked to the Hiroshima Jissen Girls’ High School (now Shudo University Hiroshima Kyoso Junior & Senior High School, located in the city’s Nishi Ward), which was the Electric Railway School’s sister institute. On the way, she could hear groans from underneath collapsed homes and saw bodies of the dead with their heads immersed in a water tank. When she looked down at a river from a walkway parapet, floating corpses completely covered the water’s surface.

It was after dark when she finally arrived at her school. A stream of wounded people who worked for the railway company were carried into the school. The bodies of those who had died were kept in the library next to the school auditorium. According to the Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster, 185 streetcar operators and engineers among a total of about 950 employees who were on duty that day as well as about 30 students at the railway school lost their lives in the bombing.

Ms. Sasaguchi, in her school uniform, continued caring for the wounded. She removed maggots festering in the wounds of survivors and slept bundled all together in the auditorium without any change of clothes. The following day, however, some people were found to have died. When she carried the bodies to a hill behind the school, men threw them into a big hole for cremation. “I saw the corpse of a girl student I knew. I became frightened and ran away,” said Ms. Sasaguchi.

It was in the evening of August 8 when she heard that the streetcar operations would begin the following day. After direction from her instructor, she began work as a conductor between the areas of Koi and Nishitenma the next morning. Numerous people searching for family as well as military staff rode the streetcar. When she told passengers that tried to pay the fare that “We aren’t collecting fares today,” they were pleased and thanked her.

She worked until the day before the war ended on August 15 and returned to Oda City with her sister around the 17th. The sisters suffered such symptoms as hair loss. Her older sister Kikuko died of stomach cancer at the age of 57. Fortunately, Ms. Sasaguchi has not suffered any serious illness and celebrated her 90th birthday earlier this year. “I don’t know what would have happened had the atomic bomb been dropped on August 5, the day I was working the morning shift,” a situation she said she still thinks about.

She recently visited the Senda warehouse at the head office of the railway company (located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward) and reunited with the A-bombed streetcar for the first time in a long while. “It’s amazing that the A-bombed streetcar is still running even 76 years after the bombing. I hope it will continue to encourage many people,” she said.

(Originally published on October 25, 2021)

Hopeful that symbol of recovery will continue to encourage people

One streetcar ran through Hiroshima on August 9, three days after the city had been reduced to ruins in the atomic bombing. The story continues to be told of how it was called “the first streetcar” to run in the aftermath of the bombing and served as a symbol of the city’s recovery. Satoko Sasaguchi (née Oka), 90, a member of the streetcar crew, was 14 years old at the time. Amid the chaos, she poured her soul into her work as conductor of the streetcar.

Ms. Sasaguchi was born and raised in present-day Oda City, in Shimane Prefecture. In the summer of 1944, she moved to Hiroshima City, longing for “the city” she had heard about from Kikuko, her older sister by two years who went to the Hiroshima Electric Railway Girls’ School, located in Hiroshima’s Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward). “I was overwhelmed by the buildings all lined up in rows and streetcars running through the city,” Ms. Sasaguchi said as she reminisced about that time.

She lived in the home of her sister’s homeroom teacher and went to Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School) while engaged in work at a munitions factory. The next spring, she finally was able to get into the Electric Railway Girls’ School, but had almost no chance to take classes because of World War II. She underwent only one week of training for streetcar conductor operations, during which she made desperate efforts to memorize the names of streetcar stops and phrases frequently used by conductors, such as “Does everyone have a ticket?” before she started the job.

On August 6, 1945, she was scheduled to work the afternoon shift. She was about to have breakfast at the dormitory adjacent to the school, around two kilometers from the hypocenter, when a “bluish-white light suddenly spread outside the window.” She had lost consciousness and, when awakened by pain in her lower back, found herself buried under rubble.

She crawled out from the wreckage toward light and went outside in a panic. The schoolyard was crowded with wounded girl students, whose screams were audible. Ms. Sasaguchi returned to her room in the dorm, quickly put on an air-raid hood, and headed in the direction of the Ujina area with a first-aid kit. She said smoke was coming out from under her hood, possibly due to the thermal rays from the atomic bomb.

She fled temporarily to Kanda Shrine (now in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward), then walked to the Hiroshima Jissen Girls’ High School (now Shudo University Hiroshima Kyoso Junior & Senior High School, located in the city’s Nishi Ward), which was the Electric Railway School’s sister institute. On the way, she could hear groans from underneath collapsed homes and saw bodies of the dead with their heads immersed in a water tank. When she looked down at a river from a walkway parapet, floating corpses completely covered the water’s surface.

It was after dark when she finally arrived at her school. A stream of wounded people who worked for the railway company were carried into the school. The bodies of those who had died were kept in the library next to the school auditorium. According to the Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster, 185 streetcar operators and engineers among a total of about 950 employees who were on duty that day as well as about 30 students at the railway school lost their lives in the bombing.

Ms. Sasaguchi, in her school uniform, continued caring for the wounded. She removed maggots festering in the wounds of survivors and slept bundled all together in the auditorium without any change of clothes. The following day, however, some people were found to have died. When she carried the bodies to a hill behind the school, men threw them into a big hole for cremation. “I saw the corpse of a girl student I knew. I became frightened and ran away,” said Ms. Sasaguchi.

It was in the evening of August 8 when she heard that the streetcar operations would begin the following day. After direction from her instructor, she began work as a conductor between the areas of Koi and Nishitenma the next morning. Numerous people searching for family as well as military staff rode the streetcar. When she told passengers that tried to pay the fare that “We aren’t collecting fares today,” they were pleased and thanked her.

She worked until the day before the war ended on August 15 and returned to Oda City with her sister around the 17th. The sisters suffered such symptoms as hair loss. Her older sister Kikuko died of stomach cancer at the age of 57. Fortunately, Ms. Sasaguchi has not suffered any serious illness and celebrated her 90th birthday earlier this year. “I don’t know what would have happened had the atomic bomb been dropped on August 5, the day I was working the morning shift,” a situation she said she still thinks about.

She recently visited the Senda warehouse at the head office of the railway company (located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward) and reunited with the A-bombed streetcar for the first time in a long while. “It’s amazing that the A-bombed streetcar is still running even 76 years after the bombing. I hope it will continue to encourage many people,” she said.

(Originally published on October 25, 2021)