Obituary: Sunao Tsuboi traveled the world calling for nuclear abolition, and now that baton has been passed to future generations

Oct. 28, 2021

by Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer

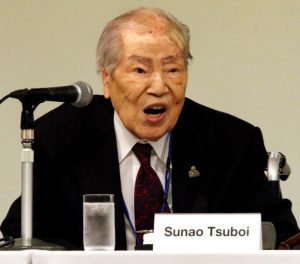

For so long continuing his call both in Japan and abroad for the elimination of nuclear weapons as the “Face of Hiroshima,” Sunao Tsuboi has died. Mr. Tsuboi experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 20 but managed to survive despite his brush with death. Marked by burn scars over his entire body, he also suffered from heart disease and cancer. With his wounds and aging body, he literally put his life on the line to continue the battle to ensure there would be no more hibakusha (A-bomb survivors).

In the New Year’s greetings that he sent out at the beginning of this year, he wrote he would limit any such greetings to this year. I thereafter happened to hear he had been hospitalized and had started to worry about his well-being.

Starting in January 2013, for a feature story series titled “My Life” based on interviews with him, I spent nearly a year speaking with Mr. Tsuboi at the offices of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Prefectural Hidankyo) and at his home, accompanying him to places at which he communicated his A-bombing experience to the public. At that time, he was 87 years old. I still remember the way he spoke with humor and his vital appearance despite his age. His voice was high yet powerful. He looked energetic at a glance and once joked that, “People who know me call me a ‘monster.’” In reality, however, he was suffering from diseases thought to have been caused by the atomic bombing.

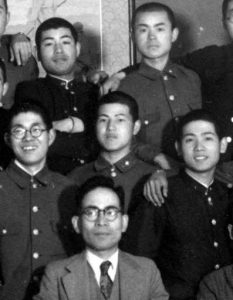

Seventy-six years ago, Mr. Tsuboi was severely burned in the bombing and taken to a temporary field hospital on Ninoshima Island, located in Hiroshima Bay in the city’s Minami Ward. Although the hospital was crowded with many wounded survivors, when his mother came to find him and yelled out his name, Mr. Tsuboi raised his hand in response while still unconscious on the bed. He was able to recover after returning to his hometown of Ondo (now the area of Ondo-cho in Kure City) and receiving care from his mother.

After his recovery, he chose to become a mathematics teacher. Children affectionately called him Mr. “Pika-don,” which is the term used to describe the atomic bombing by people in Hiroshima, as he continued to passionately convey his A-bombing experience to the students. He was in and out of the hospital several times due to anemia, taking three separate leaves of absence from the job. Nevertheless, he carried on and ultimately served as the principal of a junior high school.

Although he was engaged in peace education, he had nothing to do with the campaign to seek relief and support for A-bomb survivors. Seven years after his retirement, however, he accepted a request from the late Akira Ishida, then chair of the Japan Hibakusha Teachers’ Association, to become vice secretary general of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Prefectural Hidankyo). Later, he was promoted to the group’s position of secretary general, and from that perspective he witnessed the establishment of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, which had long been a fervent goal of A-bomb survivors. He then rose to the post of the organization’s chairperson. He also worked as co-chairperson of the Japanese Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). What he focused on most in those roles was recounting his own A-bombing experience. He traveled the world, in fact, to share his story.

In May 2016, he met with Barack Obama, the first sitting president of the United States, the nation that dropped the atomic bombs, to visit Hiroshima. Since then, his public appearances grew more and more uncommon. He was interviewed when the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017, whereupon he remarked modestly, “We shouldn’t get too carried away with the award.”

He continued to express his resentment of the government of Japan for its reliance on the U.S. nuclear umbrella despite being the only nation in the world to have suffered atomic bombings during war. He called on the citizens in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima to speak out for themselves more vigorously.

In a work of calligraphy he presented to me at the end of the aforementioned interview period, he wrote “No compromise, no surrender. Never give up!” That was the motto he used when conveying his A-bomb experience to the public. He used to say, “I want to see with my own eyes the elimination of nuclear weapons. Even if I can’t, though, I hope people in future generations succeed at that goal.” He has passed that baton of his wish to all of us.

(Originally published on October 28, 2021)

For so long continuing his call both in Japan and abroad for the elimination of nuclear weapons as the “Face of Hiroshima,” Sunao Tsuboi has died. Mr. Tsuboi experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 20 but managed to survive despite his brush with death. Marked by burn scars over his entire body, he also suffered from heart disease and cancer. With his wounds and aging body, he literally put his life on the line to continue the battle to ensure there would be no more hibakusha (A-bomb survivors).

In the New Year’s greetings that he sent out at the beginning of this year, he wrote he would limit any such greetings to this year. I thereafter happened to hear he had been hospitalized and had started to worry about his well-being.

Starting in January 2013, for a feature story series titled “My Life” based on interviews with him, I spent nearly a year speaking with Mr. Tsuboi at the offices of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Prefectural Hidankyo) and at his home, accompanying him to places at which he communicated his A-bombing experience to the public. At that time, he was 87 years old. I still remember the way he spoke with humor and his vital appearance despite his age. His voice was high yet powerful. He looked energetic at a glance and once joked that, “People who know me call me a ‘monster.’” In reality, however, he was suffering from diseases thought to have been caused by the atomic bombing.

Seventy-six years ago, Mr. Tsuboi was severely burned in the bombing and taken to a temporary field hospital on Ninoshima Island, located in Hiroshima Bay in the city’s Minami Ward. Although the hospital was crowded with many wounded survivors, when his mother came to find him and yelled out his name, Mr. Tsuboi raised his hand in response while still unconscious on the bed. He was able to recover after returning to his hometown of Ondo (now the area of Ondo-cho in Kure City) and receiving care from his mother.

After his recovery, he chose to become a mathematics teacher. Children affectionately called him Mr. “Pika-don,” which is the term used to describe the atomic bombing by people in Hiroshima, as he continued to passionately convey his A-bombing experience to the students. He was in and out of the hospital several times due to anemia, taking three separate leaves of absence from the job. Nevertheless, he carried on and ultimately served as the principal of a junior high school.

Although he was engaged in peace education, he had nothing to do with the campaign to seek relief and support for A-bomb survivors. Seven years after his retirement, however, he accepted a request from the late Akira Ishida, then chair of the Japan Hibakusha Teachers’ Association, to become vice secretary general of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Prefectural Hidankyo). Later, he was promoted to the group’s position of secretary general, and from that perspective he witnessed the establishment of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, which had long been a fervent goal of A-bomb survivors. He then rose to the post of the organization’s chairperson. He also worked as co-chairperson of the Japanese Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). What he focused on most in those roles was recounting his own A-bombing experience. He traveled the world, in fact, to share his story.

In May 2016, he met with Barack Obama, the first sitting president of the United States, the nation that dropped the atomic bombs, to visit Hiroshima. Since then, his public appearances grew more and more uncommon. He was interviewed when the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017, whereupon he remarked modestly, “We shouldn’t get too carried away with the award.”

He continued to express his resentment of the government of Japan for its reliance on the U.S. nuclear umbrella despite being the only nation in the world to have suffered atomic bombings during war. He called on the citizens in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima to speak out for themselves more vigorously.

In a work of calligraphy he presented to me at the end of the aforementioned interview period, he wrote “No compromise, no surrender. Never give up!” That was the motto he used when conveying his A-bomb experience to the public. He used to say, “I want to see with my own eyes the elimination of nuclear weapons. Even if I can’t, though, I hope people in future generations succeed at that goal.” He has passed that baton of his wish to all of us.

(Originally published on October 28, 2021)