Album discovered of war photographs of Geibi Bank, Hiroshima Bank’s predecessor: Overcoming A-bombing catastrophe, operations continued

Apr. 26, 2021

Marks of A-bombing vividly remained on ceiling and walls in offices

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

On May 6, Hirogin Holdings (HD), the parent company of the Hiroshima Bank (also known as ‘Hirogin’), located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, will open a new building that is the third-generation of structures built since World War II at the site of its former head office. The building contains new areas such as a space for consoling the souls of A-bomb victims, and a historical archive gallery called “Kioku no Kinko Museum” (Memory Vault Museum) to communicate to following generations how the bank’s employees worked to overcome the A-bombing disaster. Based on photographs and archived records kept in storage by the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives after the materials were deposited there by the Hiroshima Bank, the Chugoku Shimbun traces the bank’s history from its restoration after the bombing.

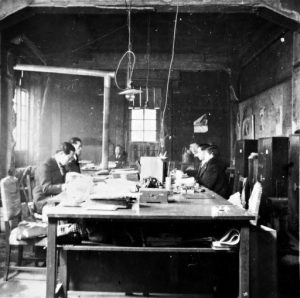

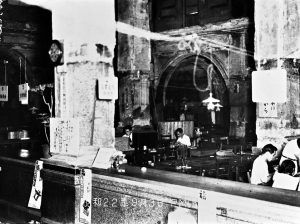

One of the scenes captured in one photo in the album of war photos shows men in business suits working in a dim office with an electric lightbulb hanging from the ceiling. Concrete is exposed on the office’s ceiling and walls, in a vivid sign of A-bombing damage. The photograph is from a Geibi Bank head office war photo album.

The 49 black-and-white photos in the album focus on the front desk with a hole, an elevator and its door knocked askew from the bomb’s blast, the president office’s crumbling wall, and other such scenes. The photos are considered to have been taken about one or two years after the atomic bombing. The album apparently was put together by the bank’s supply department in 1949.

A publication chronicling the bank’s 100-year history, published in 1979, includes testimonies from former employees, who confirmed the objects in the photos. Their testimonies included descriptions such as, “We collected the desks and chairs that had escaped the fires, made bonfires of them, and worked amid all the smoke.” Another account contained the details, “When I worked at the head office, a piece of concrete fell from the ceiling.”

The old five-story head office building was built in 1927 and had a dignified appearance. A Monday morning work meeting was scheduled to begin at 8:30 a.m. on August 6, 1945. However, at 8:15 a.m., the atomic bomb exploded above in the sky about 260 meters to the west of the building. The building was engulfed in flames, with the dead and wounded piled on top of each other inside. A total of 144 employees were killed in the bombing, including those on the way to work or serving as volunteers on a squad that engaged in the work of dismantling buildings to create fire lanes.

On August 8, under the leadership of Yutaka Ito (who died in 1972 at the age of 87), then deputy president, the bank resumed operations by using an office in the Bank of Japan’s Hiroshima branch. Mr. Ito had traveled through fierce fires and rushed to the head office from his home in the suburbs of Hiroshima. “As a banker, we have to restore our banking operations as soon as possible to stabilize people’s lives so we can get the economy moving,” he said. For customers who survived the disaster and flocked to the office, the bank paid out savings or fire insurance compensation based on their word, even if they did not happen to have a bankbook or a personal seal.

Many of the employees were wounded and had lost family members. Some of them subsequently died of acute radiation disorders. One acting deposit section manager at the branch office experienced hair loss and diarrhea and was aware he was dying, but he came to the head office to report the bank’s financial balances and other information, following which he succumbed.

Hirogin Holdings has relocated a cenotaph memorializing deceased directors and employees erected on the roof of its old head office, to the open green space on the premises of its new building, creating a new memorial space. The A-bombed pillar capstones of the Geibi Bank’s head office were also relocated from separate property owned by the bank to the new location. Staff at Hiroshima Bank’s general planning department have the following message, “We will pass on to all of our employees our corporate spirit, which has enabled us to overcome damage from the atomic bombing and continue our operations, as well as continue sending messages of peace to Japan and overseas.”

Under slogan “Restoration of Our Home,” Hiroshima Bank was active in providing loans

Bank backed reconstruction of local businesses that had nothing

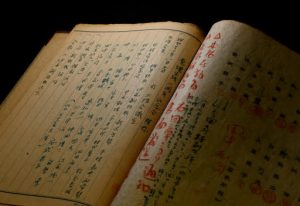

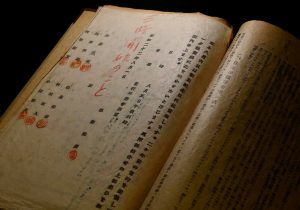

Hiroshima Bank has entrusted about 9,000 items of materials to the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives. The items the bank collected when it was putting together the publication form the core of the book celebrating the bank’s 100-year centennial. In addition to internal documents that have been created since the bank was first founded as Japan’s 66th national bank in Onomichi City, in November 1878, many precious records conveying the course of recovery after the atomic bombing are also included in the materials.

A record of a war survivors’ group meeting held on August 5, 1947, indicated, “This coming August 6 is a memorial day commemorating the war devastation. We hope to reminisce all night to remember the time we experienced two years ago.” Yutaka Ito, then vice president, took the lead in forming the survivors’ group. The record of the group’s meeting described how employees who had experienced the atomic bombing inside the head office and the directors who had worked to resume the bank’s operations from amid the ruins got together and shared their views.

After the war ended, the Geibi Bank carried out a campaign to achieve more than 10-billion yen in bank holdings based on the slogan “For restoration of our home, first and foremost, deposit your money!” In 1949, the bank started a fixed peace-deposit program with cash prizes. Recalling that time, Shigeto Ishii, 90, a former director at the bank living in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward, said, “We raised substantial amounts of money with the fixed peace-deposit program. Our main job was to raise as much money as we could and make loans to people.”

On August 6, 1950, the fifth-year anniversary of the atomic bombing, a time when Japan was still under U.S. occupation, the Geibi Bank changed its corporate name to Hiroshima Bank, as a tie-in with Hiroshima’s moniker ‘the city of peace.’ The bank promoted its financing actively to local companies and traditional stores that were working hard to restore their businesses from scratch. Chikuto Nishihara (who died in 1987 at the age of 73), a former bank employee who became manager of the loan section of the sales department at the head office in 1952, once said, “Even if debtors had no collateral, we judged their characters to determine whether or not to loan them money.”

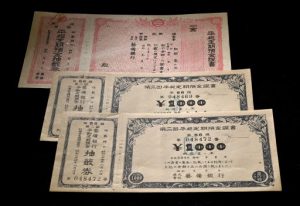

Of all the materials entrusted by the bank to the archives, 59 items including the documents partially burnt in the safe deposit box at the A-bombed branch office and certificates of the fixed peace-deposit program were returned to Hiroshima Bank last fiscal year and are now exhibited in its new archives gallery. Kosuke Nishimukai, 55, chief curator of the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives, said, “The items inform us about the operations the Hiroshima Bank conducted soon after the end of the war. Transcending the scope of assets of one company, I believe the materials are valuable in representing the larger local economy in Hiroshima during the restoration period.”

Interview with Ryohei Tanabe, former employee of Hiroshima Bank and A-bomb survivor who supported establishment of historical archive gallery

Bank’s head office was still burning day after August 6

The Chugoku Shimbun conducted an interview with Ryohei Tanabe, 86, a former employee at the bank and an A-bomb survivor living in Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward, who was in charge of putting together the publication about the bank’s 100-year history of operations from its foundation and provided cooperation for establishment of the historical archive gallery in the new building.

“After I joined the bank in 1953, I was responsible for issuing an in-house newsletter at the document section in the head office. Most of the documents were lost in the fires at the head office and branch offices located in the city at the time of the atomic bombing, but some materials remained, such as transaction records and old documents of the branch offices, which had been brought to the Miyoshi branch office beforehand to avoid the potential of damage from air raids at the time. As there were still many employees who had experienced the atomic bombing when I worked at the bank, I was able to interview them and collect their personal written accounts.

During the war, my father (Hirao Tanabe, who was then 42) worked at the investigative section at the Geibi Bank. On August 6, he was scheduled to join a volunteer squad consisting of bank employees for work on the demolition of buildings to create fire lanes in the area of Tenjin-machi (now part of Naka Ward), located just underneath the hypocenter, together with about 65 colleagues.

The following day, when my mother and I went to downtown Hiroshima to look for my father, the bank’s head office was still burning. Staying overnight on the first basement floor of the Bank of Japan’s Hiroshima branch, we looked for him for three days but failed to find any of his remains. We placed his teacup, which we had found at his office, into a grave. My mother stayed at the bank until the end of August, serving tea to employees and treating the wounded.

After the war, the bank, together with other private companies, placed importance on the bonds among people based on the spirit of needing to rise from the ruins. But as the generations have come and gone, the number of people trying to look back to the past has gradually decreased. Unlike train or electricity companies, there are few opportunities to tell the story of how banks recovered after the war. But the flow of money is the lifeblood of a local economy. The contributions made by financial organizations toward restoration of the A-bombed city should be better understood.”

(Originally published on April 26, 2021)