Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima—Recreating cityscapes: Photos of Hiroshima Communications Bureau and young Suzuko Numata

Oct. 18, 2021

A-bombed Chinese parasol tree in bureau courtyard provided emotional support for Ms. Numata

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

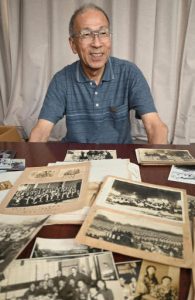

Ten years have passed since Suzuko Numata died at the age of 87. Ms. Numata, who lost her left leg in the atomic bombing, continued communicating her experience of war and feelings about the preciousness of life under a Chinese parasol tree that survived the bombing. Ms. Numata’s nephew, Ryohei, 69, of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward, has held on to photographs and other items that Ms. Numata left behind. The photos of the Hiroshima Communications Bureau (now the Chugoku Regional Office of Japan Post, located in the city’s Higashihakushima-cho, Naka Ward), where Ms. Numata worked, include those showing Ms. Numata in her youth and the government building before it burned down in the atomic bombing.

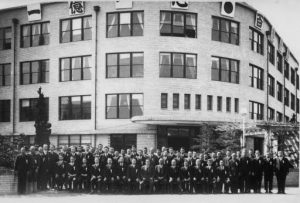

In one, men in formal attire are lined up in front of the main entrance of the Hiroshima Communications Bureau. Signs with slogans such as “The entire nation acts as one” and “Savings target—Ten billion yen” adorn the building. The national government encouraged people to save money in order to raise war funds after the start of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. That photo seems to have been taken around 1939, the time the savings target of 10 billion yen was established.

Another photo shows the bureau staff proudly riding in a U.S.-made convertible flying a banner that read “Postal Life Insurance.” According to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the photos were unknown until recently. One commemorative photo of Ms. Numata and her co-workers was taken six months before the atomic bomb was dropped.

The Hiroshima Communications Bureau was built in March 1933. It was a gentle L-shaped, steel-reinforced building standing four stories. Hideta, Ryohei’s grandfather and Ms. Numata’s father who died in 1956 at the age of 70, published trade journals at the bureau during 1929–1942. He continued to work there, along with Ms. Numata and her younger sister, even after the journals were discontinued.

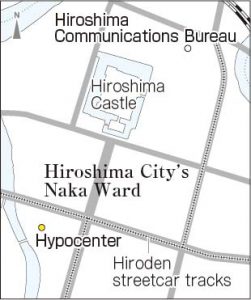

On August 6, 1945, most of the interior of the building, located about 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, was destroyed by fires after the bombing. An estimated 80 people died there. Ms. Numata was on the fourth floor and became buried under debris, injuring her left ankle. On the morning of August 10, physicians using a saw amputated her leg up to the thigh without anesthesia because the wound had turned gangrenous. She was 22. Around the same time, she learned her fiancé had been killed on the battlefield.

In despair, she contemplated suicide. However, she was encouraged by the Chinese parasol tree in the courtyard of the bureau that survived the atomic bombing. She used to say while alive that when it grew new shoots, “I felt as if the tree was saying to me, ‘Don’t die; stay alive.’”

Ms. Numata worked as a lecturer in home economics at Yasuda Women’s College. She kept her artificial leg hidden and did not speak about her A-bombing experience. However, a turning point arrived in 1981, when she was 57. At a preview run by the “10 Feet Film Project,” a grassroots campaign whereby Japanese citizens could purchase color footage filmed by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey team, Ms. Numata saw herself on screen. In the spring of 1946, she was requested by an American to show the scar on her left leg for his camera on the roof of the Teishin Hospital, and those memories came flooding back to her. Although excruciating, that experience provided her the opportunity to live as an A-bomb survivor who worked to communicate about her A-bombing experience to the public.

For the next roughly 30 years, until the end of her life, she recounted her A-bombing experience to children under the A-bombed Chinese parasol tree. A project to widely share second-generation seedlings of the tree is continued today by the city government and private-sector organizations. She was known to have visited various countries in Europe and Asia, communicating with people that had memories of Japan inflicting damage to their communities during World War II.

“My aunt never mentioned her A-bombing experience or testimony work to the family,” Ryohei said. Understanding the significance of the items she had left behind, he began organizing and digitizing the photos. “Suzuko continued sowing the seeds of peace, hoping that nuclear weapons would be abolished and that there would never again be war. I hope future generations carry on her wishes.”

(Originally published on October 18, 2021)