Silent Witness: Letters left by A-bomb victims reveal deep love of family

Jan. 10, 2022

by Miho Kuwajima and Rina Yuasa, Staff Writers

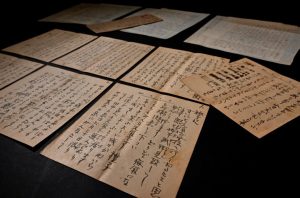

Numerous letters are included among the more than 20,000 physical artifacts archived at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in the city’s Naka Ward. A letter to a family from a child who had been moved from the urban area of Hiroshima to outside the city in the suburbs for the evacuation of schoolchildren. Letters in envelopes written by parents before they perished in the atomic bombing to children staying at an evacuation site. This year, the 77th anniversary of the atomic bombing, the Chugoku Shimbun will endeavor to trace family bonds severed by a single atomic bomb, using faded words written on aged paper as clues.

Paper stained by tears of mother who read daughter’s letter

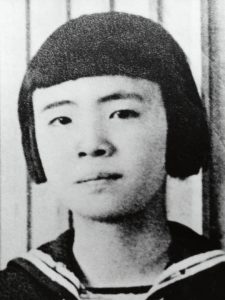

Words written on the letter are blurred by stains said to have been tears shed by the mother recalling a daughter killed in the atomic bombing. The letter was sent from Hatsue Kajiyama, then 13, to her family living in Manchuria (now part of the northeast region of China). Takiko Kajiyama, Hatsue’s mother, kept the letter in a safe place as a memento of her daughter until she herself died 11 years ago at the age of 98.

Hatsue was a second-year student at Yamanaka Girls High School, attached to Hiroshima Women’s Higher School of Education (now Hiroshima University Junior and Senior High School in Fukuyama). She wrote in the letter, “I am studying very hard every day. As tests are coming up, this time for sure I want to do well enough to be able to hold my head up in front of you all. When studying around nine at night, though, enemy fighters come and interrupt me.” Her letter paints an image of a girl who diligently studied even amid the chaos of wartime.

The Kajiyama family, consisting of 10 members encompassing three generations, originally lived in the area of Atago-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward). In the spring of 1945, the family decided to emigrate to Manchuria based on stories that the region had not suffered food shortages. Hatsue pleaded for the chance to continue her school studies and remain in Hiroshima with her grandmother, Haru Kajiyama, who was 61 at the time.

On August 6, Hatsue never returned after she had left home as part of a mobilized unit to engage in the work of demolishing buildings for the creation of fire lanes in the area of Zakoba-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), about one kilometer from the hypocenter. Haru, the grandmother, is thought to have been killed in the atomic bombing in the area of Fujimi-cho (now part of Naka Ward).

“My sister was studying so hard, using a wooden box as an alternative to a desk,” said Michiko Daimon, 87, Hatsue’s younger sister, who lives in Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward. Ms. Daimon regrets the fact that she had fought with Hatsue the night before the family left for Manchuria because Michiko’s legs became entangled with her sister’s while sleeping next to each other.

Ten months after the end of the war, Hatsue’s mother Takiko and other family members returned to Hiroshima, where she first learned of her daughter’s death. Takiko’s granddaughter, Reiko Saito, 53, a resident of the city’s Saeki Ward, looked back on the past when she said, “In her lifetime, my grandmother sometimes read over Hatsue’s letter in tears and tried to convince herself that her daughter had died instantly without suffering.”

In October last year, human remains that had been kept for years in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, located within Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, were identified as being those of Hatsue’s grandmother Haru. The remains were returned by the Hiroshima City government to the Kajiyama family. At that time, Haru’s surviving family donated Haru’s mementos and Hatsue’s letter to the museum.

Hatsue’s remains have never been found. Her letter reads, “I want to send (clothes and paper) to Michiko, Hiroko, Taketo, Shuzo, and Shizue.” Takiko had brought the letter back to Japan when they repatriated from the tumultuous Manchuria. The letter is firm proof that Hatsue, a girl who very much cared about her siblings, had indeed lived.

Letters from family members provided emotional support to live through post-war period

Kiyotaka Kyogoku, who became an A-bomb orphan when he was 12 and died at the age of 70 in 2004, never let go of the letters he had received from family members while he was at a site to which schoolchildren had been evacuated. He might have read them repeatedly unbeknownst to anyone else. Supported by the love from his parents contained in the letters, Mr. Kyogoku managed to make it through hard times during the post-war period.

A letter from Mr. Kyogoku’s father includes such thoughts as, “I am happy that you are closely following your teacher’s instructions and have become a good lad.” Elsewhere in the letter his father wrote, “Please make sure you always thoroughly clean the bowl for washing your face.” Seiso Kyogoku, who was then 45, wrote the letter to his son, who had been evacuated to the Enshoji Temple in the village of Kawachi-mura (now part of Miyoshi in Hiroshima Prefecture), in April 1945.

Mr. Kyogoku was born the oldest son of Seiso, who operated a liquor shop in the area of Nishihikimido-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), and his wife, Ayame, then 38. He always received excellent grades at school. A letter from his older sister, Kimie Kyogoku, then 17, reads, “You’ve got to pass the entrance exam for First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School,” revealing her expectations for her younger brother.

In the morning on August 6, his parents and younger sister, Yukiko, then five, were at home, located about 800 meters from the hypocenter. All died at the location to which they had later been evacuated after the bombing. Kimie, thought to have been with the family, was ultimately never found.

After having lost his parents, Mr. Kyogoku gave up his studies and raised his younger brother and sister while working at a coffee shop in the city. His wife, Miyoko, 86, said, “He never talked about the atomic bombing. It must have been hard for him to recall the experience.” Until his two daughters married, he did not obtain an Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate for fear of potential discrimination against them.

For his second daughter, Miki, 55, there was a moment she will never forget. When her father was hospitalized for lung cancer, he was unconscious and repeatedly called out for his mother in his delirium. Miki said, “I came to understand for the first time how much he had missed his mother.” Three years after Mr. Kyogoku’s death, 15 of his letters were donated to the museum.

Wrote compassionate words for sick mother

Along with the English alphabet he had just learned, Shizunori Tateishi, then 13 and a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Technical High School, wrote, “It is very fun to study. I like science, mathematics, military drills, gym class, English, and so on.” He sent the letter from his boarding house to his father, Mitsuji Tateishi, then 42, who lived in the town of Saijo-cho (now part of Shobara in Hiroshima Prefecture).

He added expressions to show his caring feelings for his mother, Harumi, then 36, who was sick, as well as for other family members. “Mother, please take care of yourself and get better soon.” He also wrote, “Are you fine and up and moving around? I am worried about you.”

At the time of the atomic bombing, Shizunori had been mobilized to work on the demolition of buildings for the creation of fire lanes and was exposed to thermal rays from the bombing in the area of Nakajima-shinmachi (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), about 600 meters from the hypocenter. According to The Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster, 187 first-year students and three teachers at his school were instantly killed. Two days later, Mitsuji went into the city of Hiroshima looking for his son, but Shizunori was never found.

According to the Peace Memorial Museum’s record of an interview with Yoriko Tateishi, Mitsuji’s oldest daughter, “I will always remember my father lamenting about how Shizunori always cared for his parents,” she had said. His mother Harumi also died at the end of August 1945.

She encouraged younger brothers, while enduring serious injury

A postcard written in messy handwriting reads, “Sorry for my bad handwriting; I wrote this note lying down.” On the day after the atomic bombing, Yuko Shikama, then 15, the oldest daughter of Ichiro Shikama, who died at age of 83 in 1986, managed to finish writing the postcard with everything she had in an attempt to offer assurance to her younger brothers while they stayed at an evacuation site. Mr. Shikama, a pastor, dedicated himself to peace activities soon after the end of the war.

Yuko was a fourth-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School). She experienced the atomic bombing at the Hiroshima Railway Bureau in the area of Kaminagarekawa-cho (now part of the city’s Naka Ward) to which she had been mobilized for work during the war. Her head was nearly crushed in the atomic bombing, leaving her seriously injured. After the bombing, she was carried to a friend’s house, but the whereabouts of her parents and Yo Shikama, then 13, her younger brother closest to her in age who had left the house for the demolition of buildings to create fire lanes, were unknown to her. In and out of consciousness due to loss of blood, she wrote the postcard to her two younger brothers, fourth-year and fifth-year students at the National School, who had been evacuated to the village of Wada (now part of Miyoshi City).

She wrote, “I am fine, but I injured my head a bit,” adding, “I believe everyone must be safe, so please hang in there!” Five days later, she was able to meet her family again and undergo intensive medical treatment in the village of Wada. Nevertheless, she died in her father’s arms on September 4.

Her father Ichiro also experienced the atomic bombing. Until 1971, he persisted in communicating to the public his A-bombing experience while also serving as a pastor at Nihon Christ Kyodan Hiroshima Church, located in the city’s Naka Ward. In 2009, Yo Shikama, who died in 2016, published a book titled “Heiwa wo jitsugen suru chikara” (in English, Power to Realize Peace), which contained his older sister’s letter and his family’s memoirs from that time.

“Whatever happens to you, hang in there, hang in there…”

The letter is packed with sentences. “As your mother I will visit you soon,” and “I will make monpe work pants wadded with cotton and send them to you by the time winter comes,” the mother wrote in an 0utpouring of love for her young daughter.

The letter was written by Chiyo Naito, then 42, to her daughter Fusako, a third-year student at Kodo National School who was evacuated to the Jodo Temple in the village of Hara (now part of Kitahiroshima-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture), in April 1945. Chiyo wrote, “Please take care of yourself, study hard, and be a smart girl,” as if she trying to comfort a daughter who was missing her family. The letter also shared updates on Fusako’s two younger sisters, who were then three-years and three-months old. “Reiko has grown up. Nahoko plays tricks on people every day,” wrote her mother.

Under circumstances in which many places throughout Japan were experiencing air raids, Fusako’s father, Kiyosaburo Naito, then 47, instructed her on how to behave. “Whatever happens to you, don’t panic, cry, or be shocked.” He continued, “Hang in there, hang in there, hang in there…,” he wrote.

On August 6, four members of the Naito family seem to have left their home, and none of their remains have ever been found. Fusako was raised by her older brother, who was discharged from military service after the end of the war. Never realized were the reunion between parents and child nor the delivery of the gift of monpe work pants wadded with cotton from the mother.

(Originally published on January 10, 2022)

Numerous letters are included among the more than 20,000 physical artifacts archived at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in the city’s Naka Ward. A letter to a family from a child who had been moved from the urban area of Hiroshima to outside the city in the suburbs for the evacuation of schoolchildren. Letters in envelopes written by parents before they perished in the atomic bombing to children staying at an evacuation site. This year, the 77th anniversary of the atomic bombing, the Chugoku Shimbun will endeavor to trace family bonds severed by a single atomic bomb, using faded words written on aged paper as clues.

Letter from daughter

Paper stained by tears of mother who read daughter’s letter

Words written on the letter are blurred by stains said to have been tears shed by the mother recalling a daughter killed in the atomic bombing. The letter was sent from Hatsue Kajiyama, then 13, to her family living in Manchuria (now part of the northeast region of China). Takiko Kajiyama, Hatsue’s mother, kept the letter in a safe place as a memento of her daughter until she herself died 11 years ago at the age of 98.

Hatsue was a second-year student at Yamanaka Girls High School, attached to Hiroshima Women’s Higher School of Education (now Hiroshima University Junior and Senior High School in Fukuyama). She wrote in the letter, “I am studying very hard every day. As tests are coming up, this time for sure I want to do well enough to be able to hold my head up in front of you all. When studying around nine at night, though, enemy fighters come and interrupt me.” Her letter paints an image of a girl who diligently studied even amid the chaos of wartime.

The Kajiyama family, consisting of 10 members encompassing three generations, originally lived in the area of Atago-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward). In the spring of 1945, the family decided to emigrate to Manchuria based on stories that the region had not suffered food shortages. Hatsue pleaded for the chance to continue her school studies and remain in Hiroshima with her grandmother, Haru Kajiyama, who was 61 at the time.

On August 6, Hatsue never returned after she had left home as part of a mobilized unit to engage in the work of demolishing buildings for the creation of fire lanes in the area of Zakoba-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), about one kilometer from the hypocenter. Haru, the grandmother, is thought to have been killed in the atomic bombing in the area of Fujimi-cho (now part of Naka Ward).

“My sister was studying so hard, using a wooden box as an alternative to a desk,” said Michiko Daimon, 87, Hatsue’s younger sister, who lives in Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward. Ms. Daimon regrets the fact that she had fought with Hatsue the night before the family left for Manchuria because Michiko’s legs became entangled with her sister’s while sleeping next to each other.

Ten months after the end of the war, Hatsue’s mother Takiko and other family members returned to Hiroshima, where she first learned of her daughter’s death. Takiko’s granddaughter, Reiko Saito, 53, a resident of the city’s Saeki Ward, looked back on the past when she said, “In her lifetime, my grandmother sometimes read over Hatsue’s letter in tears and tried to convince herself that her daughter had died instantly without suffering.”

In October last year, human remains that had been kept for years in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, located within Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, were identified as being those of Hatsue’s grandmother Haru. The remains were returned by the Hiroshima City government to the Kajiyama family. At that time, Haru’s surviving family donated Haru’s mementos and Hatsue’s letter to the museum.

Hatsue’s remains have never been found. Her letter reads, “I want to send (clothes and paper) to Michiko, Hiroko, Taketo, Shuzo, and Shizue.” Takiko had brought the letter back to Japan when they repatriated from the tumultuous Manchuria. The letter is firm proof that Hatsue, a girl who very much cared about her siblings, had indeed lived.

Letter from parents and older sister

Letters from family members provided emotional support to live through post-war period

Kiyotaka Kyogoku, who became an A-bomb orphan when he was 12 and died at the age of 70 in 2004, never let go of the letters he had received from family members while he was at a site to which schoolchildren had been evacuated. He might have read them repeatedly unbeknownst to anyone else. Supported by the love from his parents contained in the letters, Mr. Kyogoku managed to make it through hard times during the post-war period.

A letter from Mr. Kyogoku’s father includes such thoughts as, “I am happy that you are closely following your teacher’s instructions and have become a good lad.” Elsewhere in the letter his father wrote, “Please make sure you always thoroughly clean the bowl for washing your face.” Seiso Kyogoku, who was then 45, wrote the letter to his son, who had been evacuated to the Enshoji Temple in the village of Kawachi-mura (now part of Miyoshi in Hiroshima Prefecture), in April 1945.

Mr. Kyogoku was born the oldest son of Seiso, who operated a liquor shop in the area of Nishihikimido-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), and his wife, Ayame, then 38. He always received excellent grades at school. A letter from his older sister, Kimie Kyogoku, then 17, reads, “You’ve got to pass the entrance exam for First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School,” revealing her expectations for her younger brother.

In the morning on August 6, his parents and younger sister, Yukiko, then five, were at home, located about 800 meters from the hypocenter. All died at the location to which they had later been evacuated after the bombing. Kimie, thought to have been with the family, was ultimately never found.

After having lost his parents, Mr. Kyogoku gave up his studies and raised his younger brother and sister while working at a coffee shop in the city. His wife, Miyoko, 86, said, “He never talked about the atomic bombing. It must have been hard for him to recall the experience.” Until his two daughters married, he did not obtain an Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate for fear of potential discrimination against them.

For his second daughter, Miki, 55, there was a moment she will never forget. When her father was hospitalized for lung cancer, he was unconscious and repeatedly called out for his mother in his delirium. Miki said, “I came to understand for the first time how much he had missed his mother.” Three years after Mr. Kyogoku’s death, 15 of his letters were donated to the museum.

Letter from son

Wrote compassionate words for sick mother

Along with the English alphabet he had just learned, Shizunori Tateishi, then 13 and a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Technical High School, wrote, “It is very fun to study. I like science, mathematics, military drills, gym class, English, and so on.” He sent the letter from his boarding house to his father, Mitsuji Tateishi, then 42, who lived in the town of Saijo-cho (now part of Shobara in Hiroshima Prefecture).

He added expressions to show his caring feelings for his mother, Harumi, then 36, who was sick, as well as for other family members. “Mother, please take care of yourself and get better soon.” He also wrote, “Are you fine and up and moving around? I am worried about you.”

At the time of the atomic bombing, Shizunori had been mobilized to work on the demolition of buildings for the creation of fire lanes and was exposed to thermal rays from the bombing in the area of Nakajima-shinmachi (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), about 600 meters from the hypocenter. According to The Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster, 187 first-year students and three teachers at his school were instantly killed. Two days later, Mitsuji went into the city of Hiroshima looking for his son, but Shizunori was never found.

According to the Peace Memorial Museum’s record of an interview with Yoriko Tateishi, Mitsuji’s oldest daughter, “I will always remember my father lamenting about how Shizunori always cared for his parents,” she had said. His mother Harumi also died at the end of August 1945.

Letter from older sister

She encouraged younger brothers, while enduring serious injury

A postcard written in messy handwriting reads, “Sorry for my bad handwriting; I wrote this note lying down.” On the day after the atomic bombing, Yuko Shikama, then 15, the oldest daughter of Ichiro Shikama, who died at age of 83 in 1986, managed to finish writing the postcard with everything she had in an attempt to offer assurance to her younger brothers while they stayed at an evacuation site. Mr. Shikama, a pastor, dedicated himself to peace activities soon after the end of the war.

Yuko was a fourth-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School). She experienced the atomic bombing at the Hiroshima Railway Bureau in the area of Kaminagarekawa-cho (now part of the city’s Naka Ward) to which she had been mobilized for work during the war. Her head was nearly crushed in the atomic bombing, leaving her seriously injured. After the bombing, she was carried to a friend’s house, but the whereabouts of her parents and Yo Shikama, then 13, her younger brother closest to her in age who had left the house for the demolition of buildings to create fire lanes, were unknown to her. In and out of consciousness due to loss of blood, she wrote the postcard to her two younger brothers, fourth-year and fifth-year students at the National School, who had been evacuated to the village of Wada (now part of Miyoshi City).

She wrote, “I am fine, but I injured my head a bit,” adding, “I believe everyone must be safe, so please hang in there!” Five days later, she was able to meet her family again and undergo intensive medical treatment in the village of Wada. Nevertheless, she died in her father’s arms on September 4.

Her father Ichiro also experienced the atomic bombing. Until 1971, he persisted in communicating to the public his A-bombing experience while also serving as a pastor at Nihon Christ Kyodan Hiroshima Church, located in the city’s Naka Ward. In 2009, Yo Shikama, who died in 2016, published a book titled “Heiwa wo jitsugen suru chikara” (in English, Power to Realize Peace), which contained his older sister’s letter and his family’s memoirs from that time.

Letter from parents

“Whatever happens to you, hang in there, hang in there…”

The letter is packed with sentences. “As your mother I will visit you soon,” and “I will make monpe work pants wadded with cotton and send them to you by the time winter comes,” the mother wrote in an 0utpouring of love for her young daughter.

The letter was written by Chiyo Naito, then 42, to her daughter Fusako, a third-year student at Kodo National School who was evacuated to the Jodo Temple in the village of Hara (now part of Kitahiroshima-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture), in April 1945. Chiyo wrote, “Please take care of yourself, study hard, and be a smart girl,” as if she trying to comfort a daughter who was missing her family. The letter also shared updates on Fusako’s two younger sisters, who were then three-years and three-months old. “Reiko has grown up. Nahoko plays tricks on people every day,” wrote her mother.

Under circumstances in which many places throughout Japan were experiencing air raids, Fusako’s father, Kiyosaburo Naito, then 47, instructed her on how to behave. “Whatever happens to you, don’t panic, cry, or be shocked.” He continued, “Hang in there, hang in there, hang in there…,” he wrote.

On August 6, four members of the Naito family seem to have left their home, and none of their remains have ever been found. Fusako was raised by her older brother, who was discharged from military service after the end of the war. Never realized were the reunion between parents and child nor the delivery of the gift of monpe work pants wadded with cotton from the mother.

(Originally published on January 10, 2022)