Summer when Ms. Nakai first speaks about her determination to support Shin-chan, her brother with A-bomb microcephaly

Aug. 6, 2021

Days when she could not face her brother

Mushroom Club brings rays of hope

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

Those who were exposed to the atomic bomb while in their mother’s womb and born with severe intellectual and physical disabilities are called “A-bomb microcephaly” survivors. It is estimated that there are 15 microcephaly survivors across the country. Shinichi Nakai, 75, a resident of Yokohama City, is one of them and was exposed to the atomic bomb while still in his mother’s womb in Hiroshima on August 6, 76 years ago. His sister, 70, shared memories of her family for the first time this summer, with the hope that her words would convey the cruelty of A-bomb radiation damage. They showed us the history of a family that has lived a desperate and distorted life shattered by the atomic bomb.

“Shin-chan.” That’s what Yoko calls her brother. Their parents passed away a long time ago, and they live together in a condominium in the suburbs. Her brother goes to a welfare workshop located about 30 minutes by bus from their home four times a week. At home, he enjoys watching historical dramas on TV and embroidering, which he learned at a workshop, and washing the dishes after their meals. Now, the days with her kind and gentle brother go by peacefully.

Lost family and right eye

Their road to a comfortable life, however, was steep, rough and hard. “I hated even hearing the word atomic bomb,” said Yoko. When her parents tried to talk about their past, she refused to listen. She says, “Their past was so miserable that any mention of it would remind me of anxiety about heredity. It is only recently that I came to be able to face that fateful day.”

On August 6, 1945, her family was at home about 700 meters west of the hypocenter. Her father, Takeo, then 31, had just moved the family to Shinichi-machi (present-day Eno-machi, Naka Ward) from Osaka after changing jobs. Her mother, Tomie, 25, was pregnant. There were four in the family; including two girls aged 5 and 3.

The atomic bomb burned Takeo’s arm, and countless pieces of glass fragments pierced into Tomie’s face and body. As a result of exposure to A-bomb radiation, both of them vomited blood, and lost all of their hair and teeth. Their first daughter, Fumiko, drew her last breath and died the following month.

Nuclear radiation damage was seared into Shinichi’s body, and was born on New Year’s Day in 1946. A tumor was found behind his right eye, and his entire eyeball was removed before he turned one year old. He suffers from severe intellectual disabilities and cannot read, write or add and subtract. He could only attend elementary school for the first few months of his first year.

Yoko is five years younger than her brother. From the time she began to understand and remember the circumstances of their lives, her brother was always the center of the family’s attention. She says, “Some people threw thoughtless and cruel words at him. My parents protected him very carefully.” Even so… After moving to Yokohama, she entered elementary school. When her friends came to visit her, she would say, “Shin-chan, go to another room.”

She was the one who felt ashamed and hurt by her own words and deeds. She says, “I tried to hide my brother, who had done nothing wrong. I was disgusted with myself.” After that, she started to talk about her intellectually disabled brother to people around her.

Life without marriage

Yoko also had a difficult road. She became engaged in her mid-20s. However, her fiancé left her when she introduced her brother to him. “I will die with Shinichi.” Her gentle mother uttered such words. Without realizing it, Yoko had made a decision, “Even if I do not get married, that’s my life. I am the only one who can look after my brother.”

My brother might have microcephaly. It was Yoko who realized this when her brother was past 40 years of age. As she was living in a place far away from the A-bombed city, she did not know that the national government had added microcephaly to the list of A-bomb related diseases 20 years before, much less the name of the disease. When she came across the word microcephaly, however, it hit her. Shinichi also had a small head circumference, and any cap or hat was always too big for him.

In 1989, two years after submitting doctor’s certificate and other required documents, her brother was recognized as an A-bomb survivor. And, this “first step” later brought an unexpected connection.

Her parents, who had worried about how Shinichi’s life would unfold until their deaths, as well as her second sister, Yumiko, who survived the atomic bomb, died, leaving just Yoko and Shinichi. In the spring of 2019, she received a phone call from the Kanagawa prefectural government. They said that they would send her a newsletter of the “Kinoko-Kai (Mushroom Club) composed of microcephaly survivors and their families in Hiroshima City.

First new member in 24 years

“The encounter with the members has become a perfect gem in our lives.” Yoko said with a confident voice. “I felt that we were no longer alone. They gave us the strength to face the atomic bombing.”

The Mushroom Club had long been looking for additional members. However, a wall to protect privacy deterred their search. Therefore, the club asked each municipality to send out their newsletter to those who might suffer from microcephaly. Yoshio Nagaoka, 72, a resident of Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward and president of the club, and other board members travelled to Yokohama to see Yoko and Shinichi. Shinichi became the first new member in 24 years. In the autumn of 2020, both Yoko and Shinichi attended the club’s annual meeting in Hiroshima City, and walked around the ground where their family had been exposed to the atomic bomb.

It was just after their trip to Hiroshima that Yoko became seriously ill and required hospitalization. Fortunately, the operation was successful. But at one point during her treatment, she prepared for death and wrote a last testament. She says, “It was very hard for me to think about my brother’s future life without me by his side. I realized that I could not die before he dies.” At the same time, her feelings strengthened. “I wanted to leave evidence of my brother’s life. Sharing information about him as an A-bomb survivor may be the meaning of his birth and existence.”

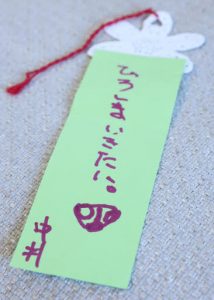

This is the reason why she decided to talk about the history of her family. She intends to visit Hiroshima again as a member of the Mushroom Club. Shinichi seems to share the same feeling. He showed us his baseball cap of the Hiroshima Toyo Carp presented to him by group members, saying, “I’m going to Hiroshima again wearing this cap.” Yoko said, sitting next to him and squinting, “Yes. Shin-chan. Let’s go to Hiroshima together again.”

Current status of A-bomb microcephaly survivors

Microcephaly survivors were once thought to have a life expectancy of 20 years. Due to the intensity of the radiation they had been exposed to during the early stages of their mothers’ pregnancy, they have suffered from intellectual and physical disabilities. After the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare announced that 16 people have been recognized as suffering from A-bomb microcephaly as of the end of March 2021, a member in Hiroshima City died in May.

The Mushroom club was founded in 1965 by microcephaly survivors and their families, who had long been subject to a society that lacked an ability to understand their plight. In 1967, with their pleas finally being accepted, the national government added microcephaly to the list of the A-bomb related diseases and given the name “short-distance early prenatal exposure syndrome.” The parents of all the members, who led the group, have all passed away, and the survivors are growing old.

(Originally published on August 6, 2021)