Special Report: Depleted Uranium Penetrators A proliferating “conventional weapon”

Apr. 3, 2000

Gulf War veterans who fell ill due to radioactive depleted uranium munitions fired by their own comrades insist, "We were told nothing," about the danger of radiation. This echoes the complaint of the vast numbers of American soldiers who contracted cancer after participating in the atmospheric nuclear testing conducted from the late 1940s into the 1960s. DU munitions are proliferating and being exported around the world as conventional weapons. But what sort of weapons are they? Why are so many US soldiers being exposed to DU particles? The following articles will use photos of the Gulf War and its victims to demonstrate the nature and effects of DU munitions.(Akira Tashiro, senior staff writer)

What is DU?

Natural uranium ore from the mine goes through an enrichment process designed to separate uranium 235 (U-235), the isotope used for nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, from uranium 238 (U-238), a low-level radioactive by-product. The highly radioactive isotope U-235 accounts for less than 1% of mined uranium; nearly all the rest is U-238.

The vast quantity of highly toxic metal (U-238) generated by this process is called "depleted uranium" or "DU." DU emits primarily alpha radiation, and its half-life is thought to be about the age of the Earth, or 4.5 billion years.

DU began accumulating in the US in the early 1940s while the Manhattan Project was developing the first atomic bombs. To date, more than 700 thousand tons have been produced, and it continues to accumulate. At the uranium enrichment plant in Paducah, Kentucky, and two other locations, DU is packed into metal containers and stored outdoors.

DU is approximately 2.5 times denser than iron and 1.7 times denser than lead. This high specific gravity means that, as a projectile fired from a tank or aircraft, it carries enough kinetic energy to blast through the tough armor of a tank. Furthermore, the impact of this penetration generates extreme heat. DU is pyrophoric, meaning that it burns on impact and can set the target on fire. DU is easy to process and endless quantities can be obtained free from the Department of Energy (DOE), which controls DU and considers its use in munitions to be "utilization of waste material."

The US military first noted these advantageous features of DU in the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. It began working with such institutions as the Los Alamos National Laboratory (New Mexico) to develop DU armor piercing shells for use against the tanks of the former Soviet Union. Production began in the 1970s and 1980s at a number of military munitions factories. The weapons are tested at several firing ranges around the country.

The US military first used DU munitions in combat during the Gulf War, firing penetrators from 120 and 105mm canons mounted on tanks. Aircraft fired them from 25 or 30mm guns. The British fired DU rounds from tanks only. During Operation Desert Storm (February 24 to 28, 1991), at least 10,000 rounds of DU ammunition were fired from tanks, and at least 940 thousand were fired from aircraft.

A DU projectile from a 120mm canon weighs about 10.5 pounds (about 4.7 kilograms). One from a 30mm gun weighs about 0.67 pounds (about 300 grams). Because they burn on impact, 20 to 70% of their mass is vaporized and diffuses into the air as uranium oxide particles. It is said that when these uranium oxide particles are ingested or inhaled, the combination of radiation and high chemical toxicity can cause cancer and a wide variety of other ailments.

The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) has set the permissable internal dose of U-238 at 0.19 milligrams per day for the general public. For employees at nuclear-related facilities, the limit is 2 milligrams.

Impact of DU munitions

Of the 696 thousand American soldiers who participated in the Gulf War, about 436 thousand entered areas contaminated by DU shells.

Dan Fahey (31, photo, based in Washington, DC) of the Military Toxicity Project, a civilian watchdog group investigating the environmental and health impacts of the use and dismantling of US weapons, studied material obtained through the Freedom of Information Act and announced in March 1998 that, "About 400 thousand soldiers may have been exposed to depleted uranium."

The US Defense Department (Pentagon) attacked this estimate, claiming that his figures were utterly groundless. About eight months later, under pressure from the National Gulf War Resource Center (NGWRC) (head office: Washington, DC) created by Gulf War veterans, their families and allies, the Pentagon published a map of the areas in which DU shells were used. At that point, they admitted that about 436 thousand ground soldiers had entered areas where DU munitions were used in Kuwait and Iraq.

The hazards of DU were known before the Gulf War.

A military report in 1974 evaluating the medical and environmental effects of depleted uranium noted, "In combat situations involving the widespread use of DU munitions, the potential for inhalation, ingestion, or implantation of DU compounds may be locally significant."

Another report issued in July 1990 by the Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), a company under contract to the military, identified the hazards even more clearly. Because depleted uranium is "a low-level alpha radiation emitter" it could be "linked to cancer when exposures are internal." It further warned, "Aerosol DU exposures to soldiers on the battlefield could be significant, with potential radiological and toxicological effects."

Thus, the Pentagon knew the dangers of DU well in advance, yet did nothing to inform or educate its soldiers about that danger and took no protective measures.

In 1993, a report compiled by the General Accounting Office (GAO) stated, "The Army was not adequately prepared to deal with depleted uranium contamination." The reason given would be hard to defend to those who became casualties of this decision. "Army officials believe that DU protective methods can be ignored during battle and other life-threatening situations because DU-related health risks are greatly outweighed by the risks of combat."

This attitude cost thousands of young men and women in their twenties and thirties their health and even their lives long after the war.

Other Factors

DU munitions were not the only source of the health problems that emerged after the Gulf War. Many soldiers were given medicines never approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). They were exposed to intense smoke pollution from oil field fires, post-war destruction of Iraqi chemical weapons storehouses, and various toxic substances released during the war. Thus, numerous factors may be involved.

Among the medicines the soldiers took under orders from their officers was an antidote to biological weapons called pyrisdostigmine bromide (PB). They also received a vaccine against botulinum and a drug to protect against anthrax. According to an investigation by the NGWRC, 250 thousand troops took PB, 8,000 received botulinum vaccinations, and 150 thousand took the anthrax medicine.

A total of 696 thousand American soldiers took part in the Gulf War from August 2, 1990, when Iraq invaded Kuwait, until July 31, 1991, when the last of the soldiers came home after shipping home American tanks destroyed by friendly DU fire. Of these, 579 thousand had left the military and 117 thousand remained enlisted as of July 1999.

The Persian Gulf War

On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded and conquered neighboring Kuwait, triggering the Gulf War.

Iraq's leader, Saddam Hussein, insists that Kuwait, one of the world's major oil producing countries, is actually Iraqi territory. Taking the move as a grab for oil fields and a more dominant role among the Arab states, the US and other Western nations reacted ferociously. US President Bush, obtaining assent from the former Soviet Union and China, created a multinational force of troops from 28 nations endorsed by the UN and led by the US. Air attacks began on January 17, 1991, the ground war on February 24.

With an overwhelming show of power, the multinational force freed Kuwait on the 26th. The fighting ended on the 28th. On March 3, Iraq accepted and signed a cease-fire designed by the UN Security Council. That cease-fire agreement prohibited Iraq from researching, developing, or possessing nuclear weapons, and required it to accept a survey team from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

(Originally published on April 3, 2000)

Using Super-Heavy Nuclear Waste to Penetrate Tanks

What is DU?

Natural uranium ore from the mine goes through an enrichment process designed to separate uranium 235 (U-235), the isotope used for nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, from uranium 238 (U-238), a low-level radioactive by-product. The highly radioactive isotope U-235 accounts for less than 1% of mined uranium; nearly all the rest is U-238.

The vast quantity of highly toxic metal (U-238) generated by this process is called "depleted uranium" or "DU." DU emits primarily alpha radiation, and its half-life is thought to be about the age of the Earth, or 4.5 billion years.

DU began accumulating in the US in the early 1940s while the Manhattan Project was developing the first atomic bombs. To date, more than 700 thousand tons have been produced, and it continues to accumulate. At the uranium enrichment plant in Paducah, Kentucky, and two other locations, DU is packed into metal containers and stored outdoors.

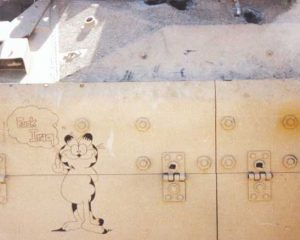

DU is approximately 2.5 times denser than iron and 1.7 times denser than lead. This high specific gravity means that, as a projectile fired from a tank or aircraft, it carries enough kinetic energy to blast through the tough armor of a tank. Furthermore, the impact of this penetration generates extreme heat. DU is pyrophoric, meaning that it burns on impact and can set the target on fire. DU is easy to process and endless quantities can be obtained free from the Department of Energy (DOE), which controls DU and considers its use in munitions to be "utilization of waste material."

The US military first noted these advantageous features of DU in the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. It began working with such institutions as the Los Alamos National Laboratory (New Mexico) to develop DU armor piercing shells for use against the tanks of the former Soviet Union. Production began in the 1970s and 1980s at a number of military munitions factories. The weapons are tested at several firing ranges around the country.

The US military first used DU munitions in combat during the Gulf War, firing penetrators from 120 and 105mm canons mounted on tanks. Aircraft fired them from 25 or 30mm guns. The British fired DU rounds from tanks only. During Operation Desert Storm (February 24 to 28, 1991), at least 10,000 rounds of DU ammunition were fired from tanks, and at least 940 thousand were fired from aircraft.

A DU projectile from a 120mm canon weighs about 10.5 pounds (about 4.7 kilograms). One from a 30mm gun weighs about 0.67 pounds (about 300 grams). Because they burn on impact, 20 to 70% of their mass is vaporized and diffuses into the air as uranium oxide particles. It is said that when these uranium oxide particles are ingested or inhaled, the combination of radiation and high chemical toxicity can cause cancer and a wide variety of other ailments.

The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) has set the permissable internal dose of U-238 at 0.19 milligrams per day for the general public. For employees at nuclear-related facilities, the limit is 2 milligrams.

No protection from known danger

Impact of DU munitions

Of the 696 thousand American soldiers who participated in the Gulf War, about 436 thousand entered areas contaminated by DU shells.

Dan Fahey (31, photo, based in Washington, DC) of the Military Toxicity Project, a civilian watchdog group investigating the environmental and health impacts of the use and dismantling of US weapons, studied material obtained through the Freedom of Information Act and announced in March 1998 that, "About 400 thousand soldiers may have been exposed to depleted uranium."

The US Defense Department (Pentagon) attacked this estimate, claiming that his figures were utterly groundless. About eight months later, under pressure from the National Gulf War Resource Center (NGWRC) (head office: Washington, DC) created by Gulf War veterans, their families and allies, the Pentagon published a map of the areas in which DU shells were used. At that point, they admitted that about 436 thousand ground soldiers had entered areas where DU munitions were used in Kuwait and Iraq.

The hazards of DU were known before the Gulf War.

A military report in 1974 evaluating the medical and environmental effects of depleted uranium noted, "In combat situations involving the widespread use of DU munitions, the potential for inhalation, ingestion, or implantation of DU compounds may be locally significant."

Another report issued in July 1990 by the Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), a company under contract to the military, identified the hazards even more clearly. Because depleted uranium is "a low-level alpha radiation emitter" it could be "linked to cancer when exposures are internal." It further warned, "Aerosol DU exposures to soldiers on the battlefield could be significant, with potential radiological and toxicological effects."

Thus, the Pentagon knew the dangers of DU well in advance, yet did nothing to inform or educate its soldiers about that danger and took no protective measures.

In 1993, a report compiled by the General Accounting Office (GAO) stated, "The Army was not adequately prepared to deal with depleted uranium contamination." The reason given would be hard to defend to those who became casualties of this decision. "Army officials believe that DU protective methods can be ignored during battle and other life-threatening situations because DU-related health risks are greatly outweighed by the risks of combat."

This attitude cost thousands of young men and women in their twenties and thirties their health and even their lives long after the war.

Other Factors

DU munitions were not the only source of the health problems that emerged after the Gulf War. Many soldiers were given medicines never approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). They were exposed to intense smoke pollution from oil field fires, post-war destruction of Iraqi chemical weapons storehouses, and various toxic substances released during the war. Thus, numerous factors may be involved.

Among the medicines the soldiers took under orders from their officers was an antidote to biological weapons called pyrisdostigmine bromide (PB). They also received a vaccine against botulinum and a drug to protect against anthrax. According to an investigation by the NGWRC, 250 thousand troops took PB, 8,000 received botulinum vaccinations, and 150 thousand took the anthrax medicine.

A total of 696 thousand American soldiers took part in the Gulf War from August 2, 1990, when Iraq invaded Kuwait, until July 31, 1991, when the last of the soldiers came home after shipping home American tanks destroyed by friendly DU fire. Of these, 579 thousand had left the military and 117 thousand remained enlisted as of July 1999.

The Persian Gulf War

On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded and conquered neighboring Kuwait, triggering the Gulf War.

Iraq's leader, Saddam Hussein, insists that Kuwait, one of the world's major oil producing countries, is actually Iraqi territory. Taking the move as a grab for oil fields and a more dominant role among the Arab states, the US and other Western nations reacted ferociously. US President Bush, obtaining assent from the former Soviet Union and China, created a multinational force of troops from 28 nations endorsed by the UN and led by the US. Air attacks began on January 17, 1991, the ground war on February 24.

With an overwhelming show of power, the multinational force freed Kuwait on the 26th. The fighting ended on the 28th. On March 3, Iraq accepted and signed a cease-fire designed by the UN Security Council. That cease-fire agreement prohibited Iraq from researching, developing, or possessing nuclear weapons, and required it to accept a survey team from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

(Originally published on April 3, 2000)