Survivors’ Stories: Shigeko Sasamori, 89, U.S. state of California—Traveled to U.S. to receive treatment for burn scars on face

Apr. 18, 2022

Following career as nurse in nation that dropped A-bomb, she stresses “preciousness of life”

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

Ten years after the atomic bombing, several young women with severe burns on their faces and other parts of the body caused by fires from the bombings traveled to the United States to receive medical treatment. Shigeko Sasamori (née Nimoto), 89, was one of those women. Ms. Sasamori has continued to communicate her experience in the atomic bombing to the public. “The support I’ve received from so many people has made me who I am today,” she said. “That’s why I want to pay it forward as long as I’m alive.” The Chugoku Shimbun held an online interview with Ms. Sasamori while she was at her home, located on the outskirts of Los Angeles.

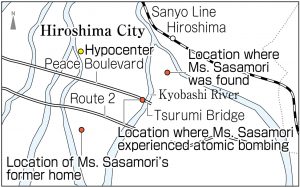

That day, August 6, 1945, changed her life dramatically. Ms. Sasamori was at the western end of Tsurumi Bridge (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward) because she had been mobilized for the work of cleaning up building demolition sites for the creation of fire lanes in the city. She was a first-year student at Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School (now, Hiroshima Shoyo High School). When the work was about to begin, she heard the sound of an airplane and looked up at the sky. The aircraft’s body was shining from the sun in the blue sky and looked beautiful. “Hey, look,” she said to her classmate, pointing at the plane. She noticed something dropping from the plane. Right then, she was blown backward by tremendous pressure from the blast.

She seemingly lost consciousness for a while. When she came to, everything around her was pitch black. She was swept along in a crowd of people who were fleeing and arrived at Danbara National School (now part of Minami Ward) located on the opposite bank of the river. On the verge of death, she deliriously repeated her home address of Senda-machi 1-chome. A man who was passing by heard her words and contacted her parents. Five days after the bombing, when her mother came to find her and called out her name, she apparently replied in a weak voice, “I’m here.”

Her face was badly burned and swollen. She could open neither her eyes nor mouth. Later, her mother told her she looked like burnt toast. She would have died had her mother not found her at that time.

Back at home, her mother was always at her side providing her with care. Her mother would tear cloth she found at home into small pieces, soak them in cooking oil, and wipe pus from her daughter’s body with them. Ms. Sasamori got better little by little, but she was unable to return to school due to her lengthy recovery. With her fingers stuck together and her mouth unable to open as she wanted, she became physically disabled.

Several years later, Ms. Sasamori was drawn inside by a hymn she heard from outside the Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church (now in the city’s Naka Ward), at which time she met Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto. Young women with keloids on various parts of their body such as the face had already begun gathering at his church. In 1952, Ms. Sasamori traveled to Tokyo to undergo surgery for the tightened skin on her neck and hands with thanks to the efforts of Reverend Tanimoto and other supporters.

After some time, Ms. Sasamori was introduced to an American man at the church. Norman Cousins later became her adoptive father. In 1955, 25 young women were selected as having potential for functional recovery to have surgery in the United States, a country with advanced medical care.

Local media in the country intensively reported on a group of women that included Ms. Sasamori as the “Hiroshima Maidens,” who played the role of conveying the inhumane nature of the atomic bombings they had experienced firsthand.

When her surgery was completed, Ms. Sasamori came back to Japan. She returned to the United States in 1957 with the aim of becoming a nurse with support from Mr. Cousins. Her decision seems to have been influenced by the freedoms as well as the warmth from everyone she had experienced in the United States. She did not hesitate to live in the country that had dropped the atomic bombs.

She was adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Cousins, got a job as nurse, and raised a son. She then began to receive requests to talk about her experience in the atomic bombing at schools. In that process, she expanded her audiences to the U.S. Senate, the United Nations, and other people overseas.

What she has always tried to impress upon young people is the preciousness of human life. “We should never again have a war that would risk our lives. That is what my message is all about,” is a point she has consistently repeated.

Kiyoshi Tanimoto and Norman Cousins

Reverend Tanimoto was an A-bomb survivor who visited the United States in 1948, shortly after Japan’s defeat in World War II, and conveyed the actual situation of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He also is one of six people who communicated their A-bombing experiences for the publication “Hiroshima,” written by the American journalist John Hersey.

In 1949, when visiting Hiroshima for his work as editor-in-chief of a literary journal in New York City, Mr. Cousins felt concerned about local orphans who had lost their parents in the atomic bombing. Along with Mr. Tanimoto, he devoted himself to a “moral adoption” movement, in which U.S. citizens became parents offering moral support for orphans in Hiroshima including support for their livelihood and education.

Medical treatment in the United States was also a support activity on which Mr. Cousins and Reverend Tanimoto worked together. From May 1955 to November 1956, 25 unmarried female A-bomb survivors with A-bomb keloids on their face or other parts of their body received free medical treatment at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. Several Quakers, a Christian group whose adherents adopt a pledge of pacifism, offered their support during their stay in the United States. The trip to the United States was sometimes criticized because the women were undergoing medical treatment in the nation that had carried out the atomic bombing and because the young unmarried women were not the only survivors who were suffering.

(Originally published on April 18, 2022)