Survivors’ Stories: Hideko Nagai, 91, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima City—Worried parents called out for their missing children

May 23, 2022

Jumped repeatedly while walking on hot ground to meet up with evacuated family

by Rina Yuasa, Staff Writer

Hideko Nagai, 91, experienced the atomic bombing about 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter when she was 15 years old. Ms. Nagai will never forget the sight of parents searching for their children in the central area of Hiroshima City after the atomic bombing. Since the end of that war, she has lived an ordinary life, which has included her enjoyment in cheering on the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, a professional baseball team that aided in the city’s recovery.

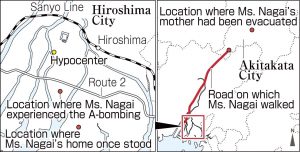

At the time of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Ms. Nagai was a third-year student at a girls school in the city and happened to be working at the branch building of the Hiroshima Chokin Bank, located in the area of Senda-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). She was engaged in work as a mobilized student for the clearing of debris. Her house was in the part of the city known as Ujina (now part of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward), where she lived with her father and aunt. Her mother had been evacuated with her younger brother and sister to an acquaintance’s house in Yoshida (now part of Akitakata City).

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Nagai, from the window on the third floor of the Hiroshima Chokin Bank, was looking at the clock tower across the road at the Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now Hiroshima University). At that moment, the hands of the clock pointed to 8:15. Suddenly, she was overwhelmed by a flash of light and her head and back became embedded with fragments of shattered glass from the blast of the atomic bomb.

After some time had passed, when she had the chance to look around, she saw that almost all the buildings along the street had collapsed. Skin burned and hanging from their bodies, people were fleeing in her direction from the city center. They looked to be nearly naked.

On the bridge she crossed in an attempt to return home, numerous people were lying down and using the broken bridge railing like a pillow to support their heads. She could hear one feeble voice calling out, “Give me water.” Unable to do anything for the person, she simply passed by.

After finally reaching her home, she found that the roof of the house had been blown off by the bomb’s blast. Nevertheless, both her aunt, who had been at home, and her father, who had been at work, were found safe. That was the first time she had the chance to look at herself in the mirror, and she was surprised to see her face covered in blood.

Her desire to find her mother grew, and in the evening, she set off walking to the place where her mother and siblings had been evacuated, approximately 50 kilometers away.

To reach that spot, Mr. Nagai was forced to pass through the city center. She walked on the ground hot from the fires that arose after the atomic bombing by alternately walking and jumping.

After drawing nearer the hypocenter, she witnessed many parents desperately searching for children who had been mobilized for work to help demolish buildings to create fire lanes in the city. Calling out their names, the parents pushed aside piles of corpses in the hopes of finding their children.

She also observed a woman who appeared to be a mother saying to the nearly naked dead body of a child, “I finally found you. You must have been hot. Let’s go home together.” The woman put a new shirt and pants on the child and carried the dead body in her arms.

At an open space next to the former Hiroshima Branch of the Sumitomo Bank near the hypocenter, soldiers were loading dead bodies onto trucks, repeatedly identifying the victims as “male, female, or sex unknown.” Around the Aioi Bridge, a short distance from the bank, the many dead bodies that had floated down the river were collecting at the bridge girders. “I didn’t feel scared because I couldn’t believe the things I witnessed were of this world,” said Ms. Nagai.

She passed through the city center and continued walking for hours in a northerly direction. It was pitch dark. With no lights on the mountain road, she proceeded to walk ahead using as a guide the sounds of a nearby stream.

During the night, she walked the remaining 10 kilometers and reached the area of Yachiyo (now part of Akitakata City). One of the local residents let her stay at their home. The next morning, she caught a ride in a truck and finally met up with her mother and siblings.

After the war, Ms. Nagai worked in Hiroshima as an instructor at a dressmaking school and as a clerk at a number of companies. She also enthusiastically cheered for the Carp baseball team with her female colleagues. “We were the original Carp ladies,” she said.

When the Carp won the championship for the first time in 1975, Ms. Nagai exchanged high-fives with people gathered in the city’s entertainment district and shared the joy of victory with them. That was the moment she realized that Hiroshima had truly recovered.

Now she enjoys watching Carp baseball games in her living room. Whenever images of the Russian military’s invasion of Ukraine appear on the television, however, her memories of the atomic bombing return. “Ultimately, it’s always members of the public who suffer the most. We must eliminate war.” Her desire for peace has grown stronger with time.

(Originally published on May 23, 2022)