Thoughts from Hiroshima: How to preserve materials left by A-bomb survivors to prevent being scattered, lost after their death

May 30, 2022

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

As news continues of the deaths of aging A-bomb survivors who spent time sharing their A-bombing experiences and engaging in peace activities, the question of how materials left behind should be preserved has become an important one. Materials such as letters and personal notes in which are inscribed stories of A-bomb survivors’ lives and thoughts following the atomic bombing are at particular risk of being scattered and lost, with few public-sector systems in place for collection and archiving. Members of the public engaged in organizing the materials and experts in the field have pointed out the need for the Hiroshima City, Prefectural, and national governments to cooperate with each other to create a guidelines for preservation and to secure an appropriate site for archiving the materials, urgent work in which they advise both the public and private sectors be involved.

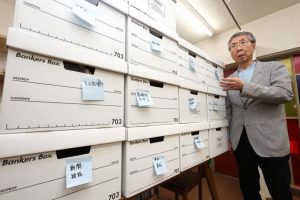

One of the rooms at ANT-Hiroshima, a non-profit organization based in the city’s Naka Ward, is crammed with more than 20 cardboard boxes with, at the very least, thousands of documents and photographs left behind in her home in Higashi Ward when the late A-bomb survivor Emiko Okada died last year in April at the age of 84.

Ms. Okada was eight years old when she lost her sister in the atomic bombing, which she experienced at her home 2.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. She continued speaking to the public of her A-bombing experience and working actively for the sake of peace up until her death. Her bereaved family entrusted the materials to ANT-Hiroshima, which had worked closely with Ms. Okada when she was alive. The organization is now making a record in the hopes that the materials can be archived at a public organization in the future.

Masaki Kano, 67, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward who is former director of the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims (in the city’s Naka Ward), works on sorting the materials on a volunteer basis. “By reading through them, I can come to a clear understanding of how she lived her life after August 6, and her feelings and activities behind her A-bombing testimonies,” he said.

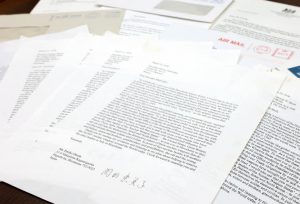

While alive, Ms. Okada actively worked on calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Among the materials she left behind are letters written in English to leaders of the seven countries scheduled to visit Japan next year before they traveled to Japan to participate in the 2008 Group of Eight Summit (the G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit, attended by what was at that time of group of eight industrialized nations), requesting their visit to the A-bombed city of Hiroshima.

The United States, England, France, and Russia, all nuclear weapons states, were among the group of countries, although Russia was excluded from the member ranks after it forcibly annexed Crimea in southern Ukraine in 2014. “I ask that you visit Hiroshima to see and listen directly to what happened here to ensure that such horrific weapons are never used again.” As Hiroshima is set to serve as host next year of a G7 summit for the first time, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and suggestion of its possible use of nuclear weapons, the message in Ms. Okada’s letters urgently resonates.

Ms. Okada’s scheduling planner and notes written around January of last year, when she was in the hospital, represent some of the varied sources of information from which can be gleaned Ms. Okada’s thoughts and activities before her death. “Humans charred in the atomic bombing” and “Ratification of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” are sentiments included in the notes.

Mr. Kano said, “I wish there was an organization that would accept all of her materials together so we could come to know the course of her life.” However, a suitable place has not been found to this point in time. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (located in the city’s Naka Ward) mainly collects artifacts of the victims who died in and immediately after the atomic bombing and photographs depicting the devastation. The National Peace Memorial Hall collects portraits of the deceased and A-bombing notes and memoirs. Both facilities already contain voluminous materials but limited space for storage. The Peace Memorial Museum’s library receives donations of documents of relatively recent vintage, with its repository nearly full.

Mr. Kano believes that the parties concerned need to view the preservation of materials as a common goal and take necessary measures by obtaining financial support from the national government. Something has to be done quickly to collect and archive valuable materials as more such cases arise against the backdrop of A-bomb survivors continuing to age and die.

The materials left by Mitsuo Kodama, who experienced the A-bombing when he was a first-year student at the Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School in the city’s Naka Ward), presented a similar challenge. He continued communicating with the public about his A-bombing experience even as he underwent multiple surgeries for cancer until his death two years ago at the age of 88. He had been looking into how his former classmates who experienced the bombing and were struck down by cancer spent that period of their life. Toshiko, 84, Mr. Kodama’s wife, holds on to the materials at their home in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward.

Among the materials is a draft he had written for the testimonies of his A-bombing experience as well as letters to the families of his deceased junior high school classmates. Toshiko is not sure how to organize the materials or who to contact regarding donations. “I would really like the materials to be put to good use, but I don’t know how to go about organizing everything,” she said.

The average age of A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate holders was 83.94 years as of the end of March last year. With that, such materials play an increasingly important role as the opportunity to listen to A-bomb testimonies from survivors grows more difficult every year that passes. Protecting as many of the materials as possible is indispensable in conveying the difficulties each of the survivors faced in their lives and passing on their hopes for peace to a time in the future when no more A-bomb survivors are alive. There is no time to waste in implementing such measures.

There are growing calls among experts for measures to be taken to preserve materials left by A-bomb survivors.

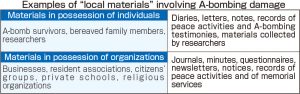

According to Chie Shijo, associate professor at Hiroshima City University’s Hiroshima Peace Institute who had previously worked as a peace museum curator, Hiroshima has been “lax in terms of collecting ‘local materials’ related to the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.” The local materials to which Ms. Shijo refers are broadly a variety of unofficial documents, such as materials from A-bomb survivors, individual researchers, and citizens’ groups working for peace.

Last year, Ms. Shijo carried out interview surveys of museum staff and of workers at the Hiroshima City Archives and Hiroshima Prefectural Archives. In a paper on results from the survey, she stressed that none of the three organizations was actively seeking out local materials related to the atomic bombing, with the Peace Memorial Museum focusing on exhibits of artifacts and photographs and the two archives organizations stressing the archiving of government documents and historical materials covering a broad period of time. Lack of storage space and skilled labor for organizing the materials is part of the underlying reason for the limited range of archived materials.

Ms. Shijo described the situation. “These documents represent a foothold based on which the A-bombing tragedy can begin to be understood from multiple points of view. The organizations first need to work in close cooperation, creating a strategic guidelines for actively collecting and archiving such local materials.”

At present, it is difficult for citizens and researchers to find the information they seek because a system is not in place to comprehensively search for the documents stored in different locations. Also unclear is who to contact when people are at the stage of considering donation of their belongings. For that reason, Akiko Kubota, assistant professor at the Research Institute for Radiation Biology Medicine in Hiroshima University (RIRBM) who specializes in the archiving of information, stressed the need to establish an “A-bombing archive,” which would serve as a hub organization for the preservation and posting of assorted materials related to the atomic bombings.

“This is an important role that Japan can play in order for the world to come to terms with the devastation caused by nuclear weapons. I often hear requests from researchers overseas of their hopes for the establishment of such an organization.” Ms. Kubota said she hopes that the governments of Hiroshima City, Hiroshima Prefecture, and Japan can work together to study the idea by speaking with and listening to the A-bomb survivors and members of the public. Considering the size and nature of the buildings of the former Army Clothing Depot (in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward) that survived the atomic bombing, she proposes to use as the archive part of the remaining four buildings, three of which are in the possession of the prefecture and one of which is owned by the national government.

The Hiroshima City government, which established the Peace Memorial Museum, also considers document preservation to be an important issue. The city government’s Peace Promotion Division stated that, “In addition to the lack of storage space, there are other problems—for example, what kind of documents would be accepted and how to handle personal information if it is included in the materials—that would need to be resolved. We want to start examining how this should take place in the future.”

(Originally published on May 30, 2022)

As news continues of the deaths of aging A-bomb survivors who spent time sharing their A-bombing experiences and engaging in peace activities, the question of how materials left behind should be preserved has become an important one. Materials such as letters and personal notes in which are inscribed stories of A-bomb survivors’ lives and thoughts following the atomic bombing are at particular risk of being scattered and lost, with few public-sector systems in place for collection and archiving. Members of the public engaged in organizing the materials and experts in the field have pointed out the need for the Hiroshima City, Prefectural, and national governments to cooperate with each other to create a guidelines for preservation and to secure an appropriate site for archiving the materials, urgent work in which they advise both the public and private sectors be involved.

Immediate measures backed by public and private sectors needed to shore up archival system

One of the rooms at ANT-Hiroshima, a non-profit organization based in the city’s Naka Ward, is crammed with more than 20 cardboard boxes with, at the very least, thousands of documents and photographs left behind in her home in Higashi Ward when the late A-bomb survivor Emiko Okada died last year in April at the age of 84.

Ms. Okada was eight years old when she lost her sister in the atomic bombing, which she experienced at her home 2.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. She continued speaking to the public of her A-bombing experience and working actively for the sake of peace up until her death. Her bereaved family entrusted the materials to ANT-Hiroshima, which had worked closely with Ms. Okada when she was alive. The organization is now making a record in the hopes that the materials can be archived at a public organization in the future.

Masaki Kano, 67, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward who is former director of the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims (in the city’s Naka Ward), works on sorting the materials on a volunteer basis. “By reading through them, I can come to a clear understanding of how she lived her life after August 6, and her feelings and activities behind her A-bombing testimonies,” he said.

While alive, Ms. Okada actively worked on calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Among the materials she left behind are letters written in English to leaders of the seven countries scheduled to visit Japan next year before they traveled to Japan to participate in the 2008 Group of Eight Summit (the G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit, attended by what was at that time of group of eight industrialized nations), requesting their visit to the A-bombed city of Hiroshima.

The United States, England, France, and Russia, all nuclear weapons states, were among the group of countries, although Russia was excluded from the member ranks after it forcibly annexed Crimea in southern Ukraine in 2014. “I ask that you visit Hiroshima to see and listen directly to what happened here to ensure that such horrific weapons are never used again.” As Hiroshima is set to serve as host next year of a G7 summit for the first time, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and suggestion of its possible use of nuclear weapons, the message in Ms. Okada’s letters urgently resonates.

Ms. Okada’s scheduling planner and notes written around January of last year, when she was in the hospital, represent some of the varied sources of information from which can be gleaned Ms. Okada’s thoughts and activities before her death. “Humans charred in the atomic bombing” and “Ratification of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” are sentiments included in the notes.

Mr. Kano said, “I wish there was an organization that would accept all of her materials together so we could come to know the course of her life.” However, a suitable place has not been found to this point in time. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (located in the city’s Naka Ward) mainly collects artifacts of the victims who died in and immediately after the atomic bombing and photographs depicting the devastation. The National Peace Memorial Hall collects portraits of the deceased and A-bombing notes and memoirs. Both facilities already contain voluminous materials but limited space for storage. The Peace Memorial Museum’s library receives donations of documents of relatively recent vintage, with its repository nearly full.

Mr. Kano believes that the parties concerned need to view the preservation of materials as a common goal and take necessary measures by obtaining financial support from the national government. Something has to be done quickly to collect and archive valuable materials as more such cases arise against the backdrop of A-bomb survivors continuing to age and die.

The materials left by Mitsuo Kodama, who experienced the A-bombing when he was a first-year student at the Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School in the city’s Naka Ward), presented a similar challenge. He continued communicating with the public about his A-bombing experience even as he underwent multiple surgeries for cancer until his death two years ago at the age of 88. He had been looking into how his former classmates who experienced the bombing and were struck down by cancer spent that period of their life. Toshiko, 84, Mr. Kodama’s wife, holds on to the materials at their home in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward.

Among the materials is a draft he had written for the testimonies of his A-bombing experience as well as letters to the families of his deceased junior high school classmates. Toshiko is not sure how to organize the materials or who to contact regarding donations. “I would really like the materials to be put to good use, but I don’t know how to go about organizing everything,” she said.

The average age of A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate holders was 83.94 years as of the end of March last year. With that, such materials play an increasingly important role as the opportunity to listen to A-bomb testimonies from survivors grows more difficult every year that passes. Protecting as many of the materials as possible is indispensable in conveying the difficulties each of the survivors faced in their lives and passing on their hopes for peace to a time in the future when no more A-bomb survivors are alive. There is no time to waste in implementing such measures.

Lack of storage space and shortage of skilled labor are important issues; experts call for establishment of core facilities

There are growing calls among experts for measures to be taken to preserve materials left by A-bomb survivors.

According to Chie Shijo, associate professor at Hiroshima City University’s Hiroshima Peace Institute who had previously worked as a peace museum curator, Hiroshima has been “lax in terms of collecting ‘local materials’ related to the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.” The local materials to which Ms. Shijo refers are broadly a variety of unofficial documents, such as materials from A-bomb survivors, individual researchers, and citizens’ groups working for peace.

Last year, Ms. Shijo carried out interview surveys of museum staff and of workers at the Hiroshima City Archives and Hiroshima Prefectural Archives. In a paper on results from the survey, she stressed that none of the three organizations was actively seeking out local materials related to the atomic bombing, with the Peace Memorial Museum focusing on exhibits of artifacts and photographs and the two archives organizations stressing the archiving of government documents and historical materials covering a broad period of time. Lack of storage space and skilled labor for organizing the materials is part of the underlying reason for the limited range of archived materials.

Ms. Shijo described the situation. “These documents represent a foothold based on which the A-bombing tragedy can begin to be understood from multiple points of view. The organizations first need to work in close cooperation, creating a strategic guidelines for actively collecting and archiving such local materials.”

At present, it is difficult for citizens and researchers to find the information they seek because a system is not in place to comprehensively search for the documents stored in different locations. Also unclear is who to contact when people are at the stage of considering donation of their belongings. For that reason, Akiko Kubota, assistant professor at the Research Institute for Radiation Biology Medicine in Hiroshima University (RIRBM) who specializes in the archiving of information, stressed the need to establish an “A-bombing archive,” which would serve as a hub organization for the preservation and posting of assorted materials related to the atomic bombings.

“This is an important role that Japan can play in order for the world to come to terms with the devastation caused by nuclear weapons. I often hear requests from researchers overseas of their hopes for the establishment of such an organization.” Ms. Kubota said she hopes that the governments of Hiroshima City, Hiroshima Prefecture, and Japan can work together to study the idea by speaking with and listening to the A-bomb survivors and members of the public. Considering the size and nature of the buildings of the former Army Clothing Depot (in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward) that survived the atomic bombing, she proposes to use as the archive part of the remaining four buildings, three of which are in the possession of the prefecture and one of which is owned by the national government.

The Hiroshima City government, which established the Peace Memorial Museum, also considers document preservation to be an important issue. The city government’s Peace Promotion Division stated that, “In addition to the lack of storage space, there are other problems—for example, what kind of documents would be accepted and how to handle personal information if it is included in the materials—that would need to be resolved. We want to start examining how this should take place in the future.”

(Originally published on May 30, 2022)