Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima—Recreating cityscapes: Photos of Yoneda Kyoto-style dyed goods shop in Tenjin-machi Kitagumi, area close to hypocenter crowded with shops, houses

Mar. 21, 2022

Member of deceased family from vanished neighborhood: “It was hell on earth”

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

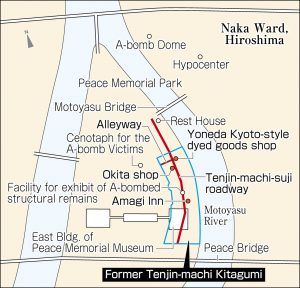

The southeast area of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (in the city’s Naka Ward), which includes the East Building of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, was once known as Tenjin-machi Kitagumi, a district crowded with shops and houses. Remnants of the district remain buried beneath the park and its lush greenery. On March 26, the Hiroshima City government is slated to open a facility for the exhibit of actual A-bombed structural remains, such as remnants of buildings and streets excavated in recent years. What sort of lives did the residents live? Herein, the Chugoku Shimbun will take a look at the area, which was close to the hypocenter and wiped out in the atomic bombing, through albums of photographs and stories of surviving members of a family that managed a Yoneda Kyoto-style dyed goods shop there.

“I only lived in Hiroshima until I was 11, but I still consider Hiroshima to be my hometown,” recounted Sakie Segawa, 88, at her home in Matsuyama City in Ehime Prefecture, on Japan’s island of Shikoku, as she looked on nostalgically at photos of the Yoneda Kyoto-style dyed goods shop in Hiroshima’s Tenjin-machi Kitagumi, where she was born and raised.

Seiso Yoneda, 86, Ms. Segawa’s brother who now lives near her home, nodded in agreement. In the photo album left by their late uncle, Hiroshi, there is one photo of the siblings when young, standing with smiles in an outdoor space on the second floor where customers’ washed kimonos were set out to dry.

Long ago, the Yonedas were a samurai family serving the Matsuyama domain (in the Shikoku region). At the end of the Edo period (1603–1868), the family moved to Hiroshima, where relatives lived, and opened a shop for the dyeing of kimonos, work in which a different relative was engaged in Kyoto. The siblings’ father, Yoshikiyo, took over the business after he learned and acquired the skills of kimono dyeing in Kyoto. Their customers included traditional inns on the island of Miyajima.

Sakie’s memories are connected to the scenery of the old neighborhood. “Cattycorner from our house was a popular footwear store run by the Okita family. We all used to look forward to ‘setsubun’ (the last day of winter in the traditional lunar calendar) because children were invited to participate in bean-scattering ceremonies to ensure good luck in the new year.” On both sides of their house were hospitals, as well as the big, Japanese-style hotel Amagi Inn, located to the south.

She still remembers the community events she took part in with her kindly father. On one occasion, they took first place in a parent-child footrace at a local sports tournament. When she had calligraphy homework that was to be displayed at the Tenma Shrine near their home, her father taught her the basics of calligraphy. “My father, who had good handwriting, said my writing was awful and made me practice repeatedly on many sheets of paper. That now has become a pleasant memory for me,” said Sakie.

After the war, which began in 1941, intensified between Japan and the United States, the shop was forced to close and the father had to begin work at a shipyard in the city. In the spring of 1945, Sakie, then in the sixth grade at a national school, and Seiso, then a fourth-grader, evacuated to a relative’s place in the Kabe-cho area with their mother.

On August 6, the single atomic bomb tore apart the family and obliterated the Tenjin-machi Kitagumi neighborhood.

Two days after the atomic bombing, their mother went back to the burned-out site and found the still smoldering cranium of their grandmother, Michiyo, 61 years old at the time, in what had been the kitchen area. Their father was missing for several days, but after excavation in the remnants of the shop, remains that appeared to be those of Yoshikiyo, then 39, as well as a pipe he smoked regularly, and the remains of their uncle, Hideso, then 36, were found. Michiyo’s older sister also died in the bombing.

At the end of 1945, the surviving mother and children moved to the mother’s parents’ home in Matsuyama City, where she raised the children while running a general store. Both Sakie and Seiso married and started their own families.

Sakie, however, continued to mourn the loss of her father. “For a long time, I didn’t believe that he had died, thinking he was still out there somewhere alive.” More than 40 years after the atomic bombing, she spotted a man in the train who looked just like her father. Her heart raced. She stared at the man until he got off the train, contemplating the whole time about whether or not she should follow him.

Seiso also is unable to shake the feelings of loneliness. He sometimes recalls the oldest son of a family that ran a nearby cosmetics store with whom he often played. “He taught me how to wrestle sumo-style on the sandy banks of the Motoyasu River. He was such a nice person.” The last time the two boys met was before his friend had evacuated from the city. Seiso does not know what happened to his friend.

The facility, which opens on March 26, includes an exhibit of the surface of a road from the Tenjin-machi-suji area alongside which the Yoneda Kyoto-style dyed goods shop was located. The siblings have expressed their interest in visiting the new facility out of a sense of nostalgia, but that is not the only reason.

Images of the countless bodies Seiso witnessed with his mother while walking around the burned ruins of Hiroshima looking for his father are etched deeply in his mind. “It was hell on earth. Such weapons should never be used,” said Seiso, as his sister nodded in agreement. What happened to cities and families when one such nuclear weapon was used?

The two siblings have increased feelings of anxiety as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has shown that the country could be readying itself to use nuclear weapons. They sincerely hope that the new exhibit can communicate to visitors the reality of the devastating consequences of nuclear weapons’ use, an act that should never be repeated.

(Originally published on March 21, 2022)