Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Photos from surveys of devastation: Photos taken by Yotsugi Kawahara detailing suffering at relief station to be donated to Peace Museum

Apr. 24, 2022

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

In August 1945, the late Yotsugi Kawahara, a member of the former Japanese Imperial Army’s photography team who died at the age of 49 in 1972, aimed his camera at locations in Hiroshima immediately after the atomic bombing, despite experiencing the bombing himself. Mr. Yotsugi took a variety of photographs, including of a temporary relief station packed with the wounded and of the incinerated center of the city. The photos he took as he traveled across the city amid the chaos for the purpose of a military survey provide important clues for further understanding about what happened when the nuclear weapon was dropped on the city. His photos continue to communicate across generations the horror of war and the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons.

Victims could do nothing but groan. A nurse wrote, “All I could do was to give them a few extra minutes before they died”

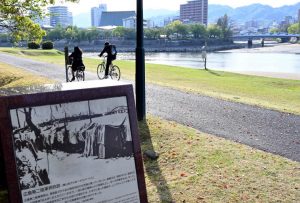

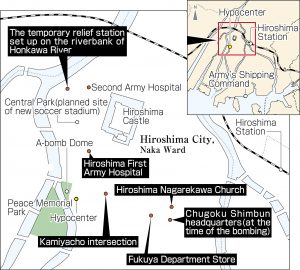

With cranes engaged in construction of a new soccer stadium in the background nearby, a stone monument stands on the riverbank of the Honkawa River, in the area of Motomachi, in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, where members of the public were on their way to school or walking by. The plaque on the monument incorporates a photo that Mr. Kawahara took at the site. Its inscription reads, “The few surviving employees constructed shelters made from straw mats and sheets of galvanized steel along the bank of the Ota River.”

The Hiroshima Second Army Hospital, located near the site about 1.1 kilometers to the north of the hypocenter, was devastated in the atomic bombing, and thus tents were set up on the riverbank as a temporary relief station. Numerous critically injured soldiers and civilians were carried to the tents in a steady procession. More than 300 people are said to have been treated at the station at one time. Mr. Kawahara took photos of the miserable state of the station filled with the wounded. Those photos are also included in the photo album that he left behind at his death.

Mr. Kawahara died at a young age. There are few records of any statements he made after World War II, but the route he followed to capture the photographic images can be discerned from his application for an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate filed shortly before his death, among other bits of information.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Mr. Kawahara was at his desk in the photography team’s office, of which he was a member, at the Army’s Shipping Command in the area of Ujina-cho (now part of Minami Ward), located about 4.6 kilometers southeast of the hypocenter. On the certificate application form, Mr. Kawahara wrote, “All of the windows in the room were shattered by the bomb’s blast but, fortunately, I was all right.”

On August 7, the following day, when heading to the central area of the city to check on staff members’ families, many of the wounded he saw would call out, “Soldier, give me water.” Later, he rode around the city on a military vehicle taking photos with Army medical officers. The photos of the Army hospital and branch hospital were taken on August 9. Because a survey team of military doctors dispatched by Japan’s Department of War visited the same location on August 9, Mr. Kawahara is thought to have taken the photos by joining the team.

A bulletin released by that survey team on August 9 indicated that 698 people, accounting for about 80 percent of the staff and patients of the Second Army Hospital, were dead or missing. The late Hatsue Kawakami, then head nurse of the relief station, took care of the victims in the tents on the riverbank, despite herself suffering a head wound. Ms. Kawakami later wrote a personal account of her experience titled Hibaku no Omoide (in English, My memory of the atomic bombing), in which she detailed the heartbreaking situation at that time.

The wounded people’s bodies were swollen because of burns suffered in the fires after the bombing. Unable to move their arms or legs, all they could do was groan. Since there was not enough medicine to go around, Ms. Kawakami was unable to provide satisfactory treatment to the wounded. She wrote, “All I could do was to give them a few extra minutes before they died.” She continued, “In the middle of the night, unable to any longer withstand the pain, patients would sometimes commit suicide by throwing themselves from the riverbank into the river. Every time the sound of big splash was heard, people would murmur numbly something about how someone else had jumped.”

The survey team’s bulletin concluded that most of the hospitals and clinics in Hiroshima had been burned to the ground, and that rescue operations were not going well, with 80 to 90 percent of about 300 physicians in Hiroshima affected by the bombing. The city suffered indiscriminate devastation and, as seen in Mr. Kawahara’s photos, even victims who were able to avoid instant death breathed their last without receiving adequate medical care.

Mr. Kawahara took photos showing the devastation of the bustling districts of the city, such as Kamiyacho and Hatchobori. After the war ended, he operated a photography shop in the city. In 1968, 23 years after the atomic bombing, he unveiled for the first time his photo album of 19 A-bomb photographs he had taken and expressed a willingness to add relevant information to each of the photos to ensure they could be easily used. Four years later, in 1972, however, he died of cancer of the adrenal gland at the age of 49, before he could successfully reach his goal.

Fifty years have passed since his death. Yuichi Kawahara, 74, Mr. Kawahara’s oldest son and a resident of the Hiroshima’s Minami Ward, is set to donate the photo album left by his father to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. “My father was fully dedicated to his work as a photographer. Because he did his work carefully, he gained a reputation as someone whose photo prints did not fade in color.” The reason for deciding to donate his father’s album to the museum is because Yuichi did not want to damage any of the photos, which continue to vividly convey the horror of the atomic bombing, by keeping them at his home.

Yuichi also showed the Chugoku Shimbun other relevant materials that have been kept together with the album. Documents related to correspondence between the late Mr. Kawahara’s wife Nuiko and the publishing companies and civic groups that asked her for use of her husband’s photos as well as published materials. Many of the materials are dated around 1980, just as the United States and the former Soviet Union were in a competition to expand their nuclear arsenals, leading to heightened concerns about possible nuclear war.

Although Mr. Kawahara’s photos were originally taken for the purpose of the military survey, he purposely held on to the images, which have served as witness to the horror of the atomic bombing. Amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the growing threat of nuclear weapons use is now reported daily in the media and elsewhere. His photos once again make us confront the tragedy of the atomic bombing, an act that should never be repeated.

A considerable number of A-bomb photos taken by people on the Japanese side were kept for surveys conducted by the military and scientists to discern the extent of devastation caused by the atomic bombing. In the chaotic immediate aftermath of the bombing, when most of the public could not simply pick up a camera and take photos because livelihoods had been destroyed, photos were taken of the incinerated ruins and wounded victims with a number of aims in mind.

After the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945, the first group that initiated a survey of the city and its environs was the military in Hiroshima. Its purpose was to identify characteristics of the new weapon and the resulting devastation and to put countermeasures in place to handle the aftermath. The admiralty office of the Imperial Japanese Navy began a survey on that same day of August 6. The Yamato Museum in Kure has in its archives photos taken on August 8 for that survey of the city of Hiroshima.

An Imperial General Headquarters survey team led by a lieutenant general entered Hiroshima on August 8 and held a joint Army-Navy panel meeting on August 10. The meeting confirmed that the weapon used on the city was an atomic bomb. A draft of the survey team’s report (now in the possession of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum) contains the photos of the relief station and other locations taken by Mr. Kawahara. Some of those photos were not included in the photo album he had left behind upon his death.

Even after the war ended, surveys continued amid a situation in which people who had experienced the atomic bombing were developing loss of hair and bleeding, symptoms now understood to be the result of radiation damage. In September 1945, a research council belonging to the former Ministry of Education established a special team to document the devastation caused by the atomic bombing. Nine subcommittees were established under the team in the various fields of medicine, physics, and so on, with related photos also taken.

Meanwhile, the U.S. military’s General Headquarters (GHQ) put in place a press code to censor and control the news media in Japan on September 19, 1945, limiting announcement of the results of such surveys conducted to grasp the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.

In many cases, the A-bomb photos taken for those surveys have been kept along with data and reports concerning the devastation, as well as physical samples. Analysis of the photos and how they connect to the relevant materials will be crucial in the effort to more clearly highlight the record of the tragedy depicted therein.

(Originally published on April 24, 2022)

In August 1945, the late Yotsugi Kawahara, a member of the former Japanese Imperial Army’s photography team who died at the age of 49 in 1972, aimed his camera at locations in Hiroshima immediately after the atomic bombing, despite experiencing the bombing himself. Mr. Yotsugi took a variety of photographs, including of a temporary relief station packed with the wounded and of the incinerated center of the city. The photos he took as he traveled across the city amid the chaos for the purpose of a military survey provide important clues for further understanding about what happened when the nuclear weapon was dropped on the city. His photos continue to communicate across generations the horror of war and the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons.

Victims could do nothing but groan. A nurse wrote, “All I could do was to give them a few extra minutes before they died”

With cranes engaged in construction of a new soccer stadium in the background nearby, a stone monument stands on the riverbank of the Honkawa River, in the area of Motomachi, in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, where members of the public were on their way to school or walking by. The plaque on the monument incorporates a photo that Mr. Kawahara took at the site. Its inscription reads, “The few surviving employees constructed shelters made from straw mats and sheets of galvanized steel along the bank of the Ota River.”

The Hiroshima Second Army Hospital, located near the site about 1.1 kilometers to the north of the hypocenter, was devastated in the atomic bombing, and thus tents were set up on the riverbank as a temporary relief station. Numerous critically injured soldiers and civilians were carried to the tents in a steady procession. More than 300 people are said to have been treated at the station at one time. Mr. Kawahara took photos of the miserable state of the station filled with the wounded. Those photos are also included in the photo album that he left behind at his death.

Mr. Kawahara died at a young age. There are few records of any statements he made after World War II, but the route he followed to capture the photographic images can be discerned from his application for an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate filed shortly before his death, among other bits of information.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Mr. Kawahara was at his desk in the photography team’s office, of which he was a member, at the Army’s Shipping Command in the area of Ujina-cho (now part of Minami Ward), located about 4.6 kilometers southeast of the hypocenter. On the certificate application form, Mr. Kawahara wrote, “All of the windows in the room were shattered by the bomb’s blast but, fortunately, I was all right.”

On August 7, the following day, when heading to the central area of the city to check on staff members’ families, many of the wounded he saw would call out, “Soldier, give me water.” Later, he rode around the city on a military vehicle taking photos with Army medical officers. The photos of the Army hospital and branch hospital were taken on August 9. Because a survey team of military doctors dispatched by Japan’s Department of War visited the same location on August 9, Mr. Kawahara is thought to have taken the photos by joining the team.

A bulletin released by that survey team on August 9 indicated that 698 people, accounting for about 80 percent of the staff and patients of the Second Army Hospital, were dead or missing. The late Hatsue Kawakami, then head nurse of the relief station, took care of the victims in the tents on the riverbank, despite herself suffering a head wound. Ms. Kawakami later wrote a personal account of her experience titled Hibaku no Omoide (in English, My memory of the atomic bombing), in which she detailed the heartbreaking situation at that time.

The wounded people’s bodies were swollen because of burns suffered in the fires after the bombing. Unable to move their arms or legs, all they could do was groan. Since there was not enough medicine to go around, Ms. Kawakami was unable to provide satisfactory treatment to the wounded. She wrote, “All I could do was to give them a few extra minutes before they died.” She continued, “In the middle of the night, unable to any longer withstand the pain, patients would sometimes commit suicide by throwing themselves from the riverbank into the river. Every time the sound of big splash was heard, people would murmur numbly something about how someone else had jumped.”

The survey team’s bulletin concluded that most of the hospitals and clinics in Hiroshima had been burned to the ground, and that rescue operations were not going well, with 80 to 90 percent of about 300 physicians in Hiroshima affected by the bombing. The city suffered indiscriminate devastation and, as seen in Mr. Kawahara’s photos, even victims who were able to avoid instant death breathed their last without receiving adequate medical care.

Mr. Kawahara took photos showing the devastation of the bustling districts of the city, such as Kamiyacho and Hatchobori. After the war ended, he operated a photography shop in the city. In 1968, 23 years after the atomic bombing, he unveiled for the first time his photo album of 19 A-bomb photographs he had taken and expressed a willingness to add relevant information to each of the photos to ensure they could be easily used. Four years later, in 1972, however, he died of cancer of the adrenal gland at the age of 49, before he could successfully reach his goal.

Fifty years have passed since his death. Yuichi Kawahara, 74, Mr. Kawahara’s oldest son and a resident of the Hiroshima’s Minami Ward, is set to donate the photo album left by his father to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. “My father was fully dedicated to his work as a photographer. Because he did his work carefully, he gained a reputation as someone whose photo prints did not fade in color.” The reason for deciding to donate his father’s album to the museum is because Yuichi did not want to damage any of the photos, which continue to vividly convey the horror of the atomic bombing, by keeping them at his home.

Yuichi also showed the Chugoku Shimbun other relevant materials that have been kept together with the album. Documents related to correspondence between the late Mr. Kawahara’s wife Nuiko and the publishing companies and civic groups that asked her for use of her husband’s photos as well as published materials. Many of the materials are dated around 1980, just as the United States and the former Soviet Union were in a competition to expand their nuclear arsenals, leading to heightened concerns about possible nuclear war.

Although Mr. Kawahara’s photos were originally taken for the purpose of the military survey, he purposely held on to the images, which have served as witness to the horror of the atomic bombing. Amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the growing threat of nuclear weapons use is now reported daily in the media and elsewhere. His photos once again make us confront the tragedy of the atomic bombing, an act that should never be repeated.

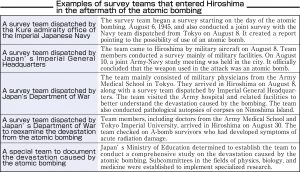

Military organizations and scientists enter Hiroshima and take numerous A-bomb photos

A considerable number of A-bomb photos taken by people on the Japanese side were kept for surveys conducted by the military and scientists to discern the extent of devastation caused by the atomic bombing. In the chaotic immediate aftermath of the bombing, when most of the public could not simply pick up a camera and take photos because livelihoods had been destroyed, photos were taken of the incinerated ruins and wounded victims with a number of aims in mind.

After the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945, the first group that initiated a survey of the city and its environs was the military in Hiroshima. Its purpose was to identify characteristics of the new weapon and the resulting devastation and to put countermeasures in place to handle the aftermath. The admiralty office of the Imperial Japanese Navy began a survey on that same day of August 6. The Yamato Museum in Kure has in its archives photos taken on August 8 for that survey of the city of Hiroshima.

An Imperial General Headquarters survey team led by a lieutenant general entered Hiroshima on August 8 and held a joint Army-Navy panel meeting on August 10. The meeting confirmed that the weapon used on the city was an atomic bomb. A draft of the survey team’s report (now in the possession of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum) contains the photos of the relief station and other locations taken by Mr. Kawahara. Some of those photos were not included in the photo album he had left behind upon his death.

Even after the war ended, surveys continued amid a situation in which people who had experienced the atomic bombing were developing loss of hair and bleeding, symptoms now understood to be the result of radiation damage. In September 1945, a research council belonging to the former Ministry of Education established a special team to document the devastation caused by the atomic bombing. Nine subcommittees were established under the team in the various fields of medicine, physics, and so on, with related photos also taken.

Meanwhile, the U.S. military’s General Headquarters (GHQ) put in place a press code to censor and control the news media in Japan on September 19, 1945, limiting announcement of the results of such surveys conducted to grasp the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.

In many cases, the A-bomb photos taken for those surveys have been kept along with data and reports concerning the devastation, as well as physical samples. Analysis of the photos and how they connect to the relevant materials will be crucial in the effort to more clearly highlight the record of the tragedy depicted therein.

(Originally published on April 24, 2022)