Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Photos from surveys of devastation, Part 4: Records of geology team

Apr. 28, 2022

Melted roof tiles, rocks hint at thermal rays

On wall near hypocenter, only nameplate remains

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

The University Museum, the University of Tokyo, located in Tokyo’s Bunkyo Ward, holds in its archives a collection of photographs of rocks damaged by the intense thermal rays from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. One photo shows a section of a wall, the upper part composed of melted and vitrified andesite, with the surface of a granite parapet peeled off.

The photos were taken by Takeo Watanabe, a geologist and professor at the University of Tokyo who died in 1986 at the age of 79. He became a member of a special committee for the investigation of A-bomb damage established by Japan’s Ministry of Education within its academic research council in September 1945, the month after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Mr. Watanabe led the investigation committee’s geology team and analyzed the thermal rays’ effects and extent of damage on rocks and other objects.

During his research in Hiroshima during the period October 11–13, 1945, Mr. Watanabe collected samples and took photos of roof tiles and rocks exposed in the atomic bombing. He wrote in his field notes, “There are signs that the roof tiles were melted.”

Analyzing melting limit

Unlike in cases of heat from fires, the surfaces of roof tiles exposed to the intensely hot thermal rays even for an instant were melted to less than one millimeter in depth and appear to have formed bubbles. Mr. Watanabe analyzed the melting limit by calculating how far from the hypocenter roof tiles had been melted by the bomb’s thermal rays. A report submitted by the committee in 1953, after the end of the occupation of Japan by Allied forces, noted that the melting limit in Hiroshima was at a point 600 meters from the hypocenter.

Temperature might have risen to 3,700 degrees Celsius

The University Museum has 87 samples collected by Mr. Watanabe in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “As Mr. Watanabe recorded precise information regarding the samples, and they were preserved in a specimen room, the samples have not deteriorated. We can examine the stones and roof tiles exposed to the atomic bombing almost as if they were new,” said Tokuhei Tagai, 78, professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo and a specialist in mineralogy. Mr. Tagai has been analyzing the samples and related materials over the past several years.

According to Mr. Tagai, by examining Mr. Watanabe’s records and roof tiles in possession of Hiroshima University, the melting limit in Hiroshima can more accurately be said to have been around the former Hiroshima Prefectural government offices, located 850 meters from the hypocenter. He also analyzed from experiments on samples that the surface temperature of roof tiles at the melting limit had reached 1,280 degrees Celsius. He calculated the thermal rays at the hypocenter using those data and found that the hypocenter was, for a short time, exposed to thermal rays that raised roof tile temperatures to around 3,700 degrees Celsius.

On the day of the atomic bombing, the thermal rays also assailed members of the public without mercy. A closer look at Mr. Watanabe’s photos conveys the horrors more distinctly.

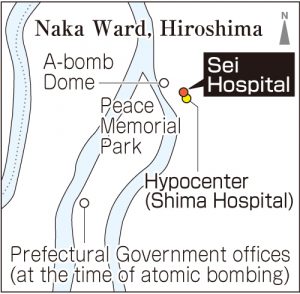

One of his photos shows a wall at Sei Hospital, located in the area of Saiku-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). Andesite used in the wall was blackened and vitrified in the bombing. The hospital was located diagonally across from Shima Hospital, which marked the A-bombing’s hypocenter. A photo taken from in front of the wall shows a sign indicating “Patients’ side gate” and the nameplate “Shigemoto Sei.”

Shigemoto Sei operated Sei Hospital as a urologist. This reporter showed the photo to his grandson Junji, 86, a resident of Mino City, Osaka Prefecture. He expressed surprise and said, “I have never seen this before.” He added nostalgically, “The nameplate was on the gatepost at my grandfather’s house.”

Mr. Sei’s house was situated behind the hospital. Before the war, Junji lived with his grandfather until he was five years old and moved to the Kansai area of Japan because of his father’s work. When living in Hiroshima, they would often buy sweets filled with red-bean jam at a shop in the neighborhood and go boating on the Motoyasu River. “I still vividly remember those happy days in Hiroshima.”

On August 6, however, the grandfather Mr. Sei experienced the atomic bombing as he continued to live in Hiroshima. His remains were found where the hospital’s consultation room had previously been located. He was 63. His son, a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Medical School (now Hiroshima University School of Medicine), also died in the bombing.

With the deaths of Mr. Sei and his son, the hospital was never reconstructed. According to Junji, he and his family visited the location of the hospital in Hiroshima around a year after the atomic bombing, but he has never visited the city since that time. “My life would have been different if it had not been for the atomic bombing. Even at my age, I still believe that,” said Junji.

The University Museum has samples of melted walls and roof tiles from Sei Hospital as well as the photos. Etched in the samples are not only signs of the thermal rays from the bombing, but also of the lives that were taken.

(Originally published on April 28, 2022)