Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Photos from surveys of devastation, Part 6: Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital

Apr. 30, 2022

Recorded devastation at hospital-turned-relief station

Took photos of patients while enduring inner conflict

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

One photograph shows a patient whose shoulder and arm had been burned by the thermal rays from the atomic bombing, resulting in scars on her back that had turned into keloids marked by raised flesh. The scars from the surgery are still raw in the photo, which was taken at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (now the Hiroshima Red Cross and Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital) in October 1945, two months after the atomic bombing by the U.S. military. Masaru Kuroishi, a radiation technician at the hospital who died in 1990 at the age of 77, took the photo under the direction of hospital physicians as part of an effort to keep a medical record before and after surgery.

Horrible scenes at hospital

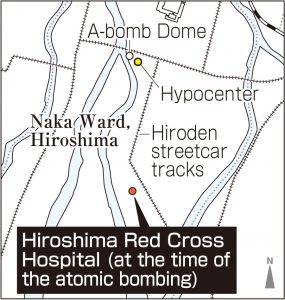

The Red Cross Hospital, located about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, suffered severe damage to the inside and outside of the building, with its windows completely blown out. The main building, a three-story reinforced-concrete structure, escaped destruction from the fires that arose after the atomic bombing. Among the hospital’s doctors, nurses, and inpatients, 56 were killed and 364 slightly or seriously injured. Still, the hospital was turned into a center for emergency aid as it became flooded with the wounded shortly after the bombing.

Mr. Kuroishi was visiting his wife’s family home in the district of Fukayasu-gun (now Fukuyama City) in Hiroshima Prefecture, starting the day before the atomic bombing. Hearing that Hiroshima had been devastated, Mr. Kuroishi made an effort to head for the city in the early morning hours of August 7, 1945. Train service on the Sanyo Line, however, was suspended. He instead took the Fukuen and Geibi train lines, arriving at the hospital around 2:30 p.m.

“The hospital yard was filled with so many wounded there was no room to walk on the grass. Both the yard and the inside of the hospital buildings were packed. I was completely uninjured and self-conscious as a result, feeling as if I should smear somebody’s blood on me and get bandaged like everyone else. The situation was that bad,” said Mr. Kuroishi, during a symposium about The History of Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Medical Treatment, which was published in 1961.

“I heard a lot from my dad about the horrible situation at the hospital,” said Mr. Kuroishi’s son, Masaki, 73, a resident of Hatsukaichi City in Hiroshima Prefecture. His aunt was a student nurse and was exposed to the atomic bombing at the hospital’s dormitory. She was involved in the relief work that took place at the hospital and in the cremation of victims’ bodies starting a few days after the atomic bombing. She saw the same scenes as Mr. Kuroishi witnessed. Masaki’s mother had also worked at the hospital as a nurse until she married Mr. Kuroishi. When the family would gather, it was only natural that the conversation would turn to the hospital.

Mr. Kuroishi took photos of patients under the direction of Fumio Shigeto, then deputy director of the hospital, and others. Together with the late Seiji Saito, a pathological examination technician, he recorded the damage to human bodies resulting from the atomic bombing.

Making efforts to preserve records

Some patients were so badly wounded it was hard to tell whether they were male or female. “I was unable to take their photos because my conscience bothered me so much, although Dr. Shigeto instructed me to take lots of photos,” said Mr. Kuroishi at the symposium. While enduring emotional conflict, he took as a medical record almost 50 photos, four of which taken before the end of 1945 are presently archived at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in the city’s Naka Ward.

In 1956, the Hiroshima Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital was attached as an annex to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital as a center for the medical care of A-bomb survivors. The two hospitals were merged in 1988. Until his retirement in 1977, Mr. Kuroishi, together with Mr. Saito, worked on the preservation of materials and biosamples related to the atomic bombing. After retirement, Mr. Kuroishi was involved in the Association of Photographers of the Atomic Bomb Destruction of Hiroshima, which had been established by Yoshito Matsushige, a friend of Mr. Kuroishi and a former staff photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun, engaging in efforts to preserve photographic records.

In his later years, Mr. Kuroishi called for preservation of the hospital building, which was to be demolished before reconstruction. “I believe it was his simple wish as a citizen who witnessed the reality of the atomic bombing to leave records of the bombing for posterity,” said Masaki. The hospital’s main building was demolished in 1993, but its window frames warped by the blast from the bombing were preserved as a monument to that time, becoming the first structure to be covered by Hiroshima City’s subsidy program for the preservation of A-bombed buildings.

Hearing reports on the invasion of Ukraine by the nuclear power Russia, Masaki is reminded of his father. “Human beings forget what happened in the past. That is why we must continue trying to appeal to people’s consciences from the perspective of Hiroshima. That is truly the significance of the preservation of historical records,” said Masaki. He is always thinking about what he can do as a member of the generation to which those records are being passed down.

(Originally published on April 30, 2022)