Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains—Nine names strengthen desire for terrible tragedy to never be repeated

Jun. 20, 2022

Daily lives taken on “that day”

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

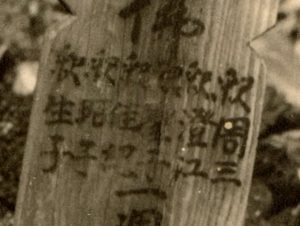

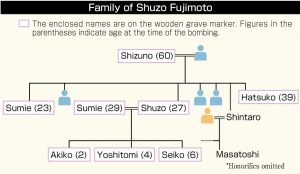

Shuzo, Sumie, Seiko, Yoshitomi, Shoko, Seiko, Hatsuko, and Shizuno are the names of the family that lived near the present-day Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims but died in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, as seen in a photograph donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum of a wooden grave marker. The Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and the Peace Memorial Museum are both located in Hiroshima’s centrally located Naka Ward. What emerged from the reporting on this story were the lives and lifestyles that existed in that location before the atomic bombing, as well as the resentment and sorrow of a surviving member of a family whose lives had been erased.

The photo of the wooden marker donated to Peace Memorial Museum two years ago shows the marker inscribed with the first names of nine unidentified A-bomb victims. One of the names is illegible, and none has a family name. This reporter searched for a family with first names that match those in the photo in archives at the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, located in the city’s Naka Ward. At the National Peace Memorial Hall, visitors can search for the names of any of the deceased, regardless of time of death, whose bereaved family members applied to register the names, except a portion (about 25,000 names were registered as of the end of fiscal 2021). Searches can also be made for family members who died at the time of the atomic bombing.

Upon checking for the names on a computer, I found two with the name Shuzo. One was Shuzo Fujimoto, who had a wife, children, and sisters, with all of the first names found on the wooden marker matching those on the computer. The family’s address was in the former Nakajima-honmachi, which is now part of Peace Memorial Park in the Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. The family was also mentioned as being A-bomb victims in one of the articles of the Chugoku Shimbun’s special series titled “Record of Hiroshima: Photographs of the Dead Speak” (published on August 3, 1999), which traced the devastation of the city.

“Those are definitely the names of my uncle and his family. This is the first time I’ve ever seen the photo. How is it even possible…,” said Masatoshi, 82, Shuzo’s nephew and a resident of Naka Ward, as the sight of the photo rendered him speechless.

Masatoshi grew up in a different part of Hiroshima City and had been evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture at the time of the dropping of the atomic bomb, when he was five years old. However, he recalls visiting the tea shop Akizuki, in Nakajima-honmachi, which was run mainly by his aunt Hatsuko and his grandmother Shizuno, who would give him candy and dried persimmons. The shop was said to be popular for its breads and coffees.

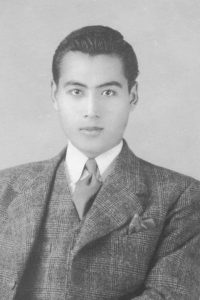

Masatoshi’s uncle Shuzo lived close to Akizuki, together with his wife and three children. While helping out in the tea shop, Shuzo also painted signboards for movie theaters in the city. His father, Shintaro, who died in 2000 at the age of 91, said to Masatoshi, “As my younger brother, Shuzo was my pride and joy.” According to Shintaro, Shuzo was a tall (180 centimeters), handsome man, and was called the “Gary Cooper of Hiroshima.” Shintaro explained how a famous actor had come to recruit Shuzo to have him work in the industry.

However, on August 6, 1945, the entire city was annihilated in the U.S. military’s atomic bombing. Five members of the Fujimoto family, including Shuzo and his wife and three children, as well as Hatsuko, Shizuno, and Masatoshi’s other aunt, Sumie, were killed in the bombing. Shintaro, who had been drafted and deployed to a military unit in Yamaguchi Prefecture, returned to Hiroshima and collected remains from the ruins of the obliterated tea shop. Masatoshi heard from his father that the remains were unidentified, but he said he had never been told of the wooden grave marker.

The resentment felt by Shintaro, whose family was taken from him by the bombing, did not subside over the years. Masatoshi said, “Every time my father would drink, he complained that just thinking about the pikadon [a combination of words that mean flash (“pika”) and boom (“don”) of the atomic bombing] made him angry and felt he would be bitter for the rest of his life.” Each August 6, he would wake up at 4:00 in the morning and visit the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, which is located in the vicinity of the location in which Akizuki once stood.

During one interview with Masatoshi, I was able to confirm the name that could not be read in the photo was that of Sumie. However, there was one name on the marker who Masatoshi had never heard of and who was not listed in the family register.

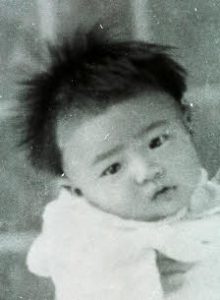

That name was Seiko. It is written at the end of the list of names of Shuzo’s family. At the time of the bombing, his wife was expecting their fourth child. It is believed that Seiko was the name to be given to the unborn child, although there is no evidence to back up that supposition.

All three of Shuzo’s children, Masatoshi’s cousins, were young, ranging from two to six years old. Masatoshi said, “Shuzo’s first daughter, Seiko, was in my grade at school and was said to have been adored. I have no memory of her, though, which is something I simply cannot bear.” His eyes filled with tears as he peered at the names on the wooden marker.

The photo is now displayed in the Peace Memorial Museum’s New Arrival Exhibit section. Masatoshi has indicated he would like to provide the museum with more photos of Shuzo’s family and the tea shop Akizuki, if the museum were to be interested. The photo provides evidence of the family’s existence until August 6, 1945, at the place where the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims now stands. He says, “It was truly a terrible tragedy. I strongly hope such a situation will never be repeated or forgotten.”

(Originally published on June 20, 2022)