Survivors’ Stories: Terumi Tanaka, 90, Saitama Prefecture―I collapsed into tears when I cremated my aunt

Aug. 9, 2022

“We should never tolerate the weapon of inhumanity,” he vows, on the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Day

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

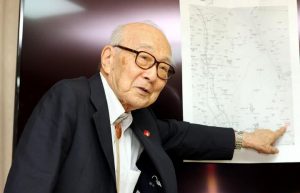

Three days after Hiroshima was destroyed by the atomic bomb, another bomb was dropped on Nagasaki by the United States armed forces. Today marks the 77th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. We asked Terumi Tanaka, 90, a former assistant professor at Tohoku University (Sendai City) who lives in Niiza City, Saitama Prefecture, about his A-bomb experience. Mr. Tanaka is now engaged in activities as Co-Chairperson of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), a national organization of A-bomb survivors’ associations, with his strong desire that “no one else should have to endure the same kind of suffering.”

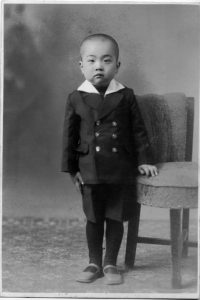

Mr. Tanaka was born near Mukden (now Shenyang) in Northeast China, where his father Tsuneo, an army officer, was transferred for a new assignment. In 1931, the year prior, the Japanese Kwantung Army caused the Manchurian Incident, and occupied Northeast China.

In 1938, Tsuneo died suddenly, so five family members, his mother Moto, older brother, two younger sisters and Mr. Tanaka, left for Nagasaki City and relied on his paternal aunt Koto Sasaki and maternal aunt Rui Yoshida.

In 1945, Mr. Tanaka entered the former Nagasaki Junior High School. Unlike in Hiroshima, first-year students in Nagasaki were not mobilized in a large-scale housing demolition to create fire lanes, and made bamboo spears to point at enemies instead. On August 9, he was supposed to have class but stayed home because an air-raid alarm was sounded. He was reading a book upstairs, waiting for the alarm to be lifted.

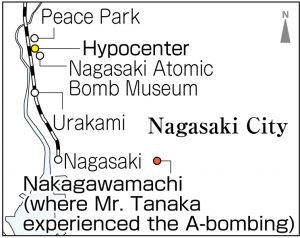

It was 11:02 a.m. He was struck by a light, as if a flashbulb had been set off in front of him, and lost consciousness with no memory of hearing a roaring sound. When he came to, he found two glass doors had fallen down on his back. Miraculously, they did not break and he could escape injury. It was 3.2 kilometers from the hypocenter.

Black smoke rose into the air, which then turned to deep red. People whose bodies were badly swollen from the burns were fleeing, and a nearby national school was crowded with the injured. It was the horrible sight. Worrying about his aunts, he headed to Urakami district, where they were living, three days after the atomic bombing. He had no way of knowing that the district was in the immediate vicinity of the hypocenter at that time, and walked around the scorched earth, where dead bodies were scattered about.

Ms. Yoshida had already been dead when he found her. Mr. Tanaka cremated her on galvanized sheet iron. When he saw the remains of his aunt, which still retained the human form, “I remembered my kind aunt and collapsed into tears there.” Ms. Sasaki had become a charred body at the devastated site of her house, with a part of her clothes remained unburnt. “It is the pattern on her clothes. She also could not survive,” Moto murmured.

At 13, he lost five family members, including his grandfather, uncle and cousin. Fearing further bombings, the family spent days in the woods near an air-raid shelter until the war ended.

The fatherless family had a difficult life for about seven years under the postwar occupation. “Sometimes we had nothing to eat for days.” He supported the family finances by working as a day laborer, loading and unloading at the Port of Nagasaki, which even a junior high school student could do. After he worked in Tokyo for five years, he entered Tokyo University of Science, which he worked his way through. After graduation in 1960, he studied solid-state engineering at Tohoku University.

He became acutely aware of the issue of the atomic bombing in 1954, when the Japanese tuna fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) was contaminated by the hydrogen bomb test conducted by the United States. The incident prompted him to join the signature drive against atomic and hydrogen bombs. On the other hand, he had some hesitation about calling himself an “A-bomb survivor,” comparing with the victims who were burnt in an instant or whose health and life were destroyed by being exposed to the bomb’s radiation at close range. He joined the activities by the A-bomb survivors’ group in Sendai around 1970. It was in 1977 that he made up his mind to share his A-bomb experience, when he could not refuse to give testimony.

He made efforts as the Secretary General of Nihon Hidankyo with the support of his wife Haruko, who passed away three years ago at the age of 86. He has been serving as the Co-Chairperson of the organization since 2017. Two important pillars of their activities are to appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons, and to call on the national government, which is responsible for starting the war, for the relief measures to be provided properly. Now, “The Japanese government does not ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which A-bomb survivors worked hard as one to realize. My feelings are already beyond anger,” Mr. Tanaka raised his voice.

“How can we make everyone understand what would happen if such a cruel and inhumane weapon was actually used?” While agonizing, he vows, “We should never tolerate weapons that kill civilians indiscriminately. I will continue appealing as long as my strength lasts.”

(Originally published on August 9, 2022)