Unknown A-bombing devastation must be uncovered—Detailed report on symposium “Memories of War: Striving to Fill Voids in Hiroshima and Nagasaki”

Jul. 26, 2022

by Hiromi Kanazaki, Yumi Morita, Junji Akechi, and Rina Yuasa, Staff Writers

On July 18, the Hiroshima Peace Institute (HPI), Hiroshima City University, the Chugoku Shimbun, and the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) at Nagasaki University jointly held an online symposium titled Memories of War: Striving to Fill Voids in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Regarding the actual condition of the atomic bombings that annihilated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, many missing pieces of the puzzle remain because of the extent of destruction, and the Japan national government’s consistent attitude of avoiding identification of the actual devastation through a full-fledged survey even after the war ended. As 77 years has passed since August 6, 1945, and with aging of atomic bomb survivors, this Chugoku Shimbun staff writer and university researchers discussed at the symposium current challenges in this effort. A total of about 300 people viewed the livestreamed symposium in screening venues located in the Chugoku Shimbun Hall and other places.

Speakers

Reports and Discussion

Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer, the Chugoku Shimbun

Mitsuhiro Hayashida, Project Researcher, RECNA, Nagasaki University

Chie Shijo, Associate Professor, HPI, Hiroshima City University

Moderator

Hibiki Yamaguchi, Visiting Researcher and Program-Specific Professor, RECNA, Nagasaki University

Emcee

Makiko Takemoto, Associate Professor, HPI, Hiroshima City University

The average age of A-bomb survivors exceeded 84 years this year. As those who continue to communicate their A-bombing experiences grow older, a diversity of activities has been broadly undertaken to pass on their A-bombing memories to future generations. Meanwhile, “voids” remain involving information about the actual devastation wrought by the atomic bombings that are not understood to this day. How such unknown areas of the devastation should be examined and placed on record is being put to the test.

The Chugoku Shimbun lost 114 employees in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. In an editorial written in 1964, the news company advocated the idea of looking at the horror of the atomic bombing in detail and conveying it to the world. Former staff writers at the Chugoku Shimbun uncovered devastation that had been buried. With their efforts in mind, in 2019 the Chugoku Shimbun began the series of articles titled “Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima,” which received the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association Award for fiscal 2020.

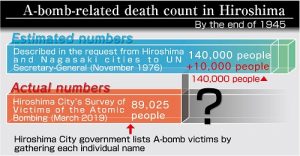

One of the series’ pillars relates to voids in the A-bombing death toll. A written request that the Hiroshima and Nagasaki City governments submitted to the United Nations in 1976 reported that the number of deaths related to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by the end of 1945 was estimated to be 140,000 (±10,000). On the other hand, a city government survey of victims of the atomic bombing that began in 1979 showed the death toll by the end of 1945 to be 89,025, as of March 2019.

Put simply, those two figures are separated by a gap of several tens of thousands of people. After a closer look, we confirmed that the government survey faced difficulties in identifying some categories of deceased, such as those in a household whose members all died in the bombing, military personnel dispatched from outside Hiroshima Prefecture, and people who were from the Korean Peninsula. One of the background factors was the national government’s passive attitude with respect to the survey investigating the entire picture of victims. Because some materials kept outside of Hiroshima Prefecture or overseas have not been used in the survey, their active utilization is now necessary.

We also reported on the remains of victims. It is said the remains of about 70,000 unclaimed victims are stored in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, with the names of 814 of such victims identified to date. The city lists the names of the unclaimed remains as it searches for bereaved family members, but Japan’s national government is not involved in such an effort, based on its idea that such work is the responsibility of local governments.

Our newspaper team then went about searching for surviving family members of victims. When the names on the city’s list were checked against the names of victims registered by their families at the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, some names with matching pronunciation and addresses were found. The work ended up with the return of some victims’ remains to family members. In another example, I found a personal note written by someone whose family name was the same as that of an unclaimed victim, leading finally to confirmation of that victim’s identity. There are things we can do with publicly disclosed information.

Moreover, the Chugoku Shimbun’s printed edition and website have introduced photographs taken in Hiroshima before the atomic bombing under the title “Recreating cityscapes.” The public-sector system whereby pre-bombing period photos are collected is insufficient. By asking our readers to seek out and provide us with relevant materials, we have received photos that escaped destruction by the fires that arose immediately after the atomic bombing from about 70 individuals and organizations. Now, about 1,200 photos with the locations at which they were taken being specified have been released to the public, conveying images of cityscapes erased in the atomic bombing.

While our team has traced the lives of victims and identified remains that had been missed in the city’s survey of A-bomb victims over such a long period, we were able to get a sense of the impact of each individual’s life. By continuously reporting victims’ records with that in mind, I believe we can clearly reveal the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons use.

Kyosuke Mizukawa

Graduated from the Faculty of Letters at the University of Tokyo and joined the Chugoku Shimbun in 2007. Before taking his current post, Mr. Mizukawa worked for the company’s news division and the Bingo area branch office. He also penned articles for the feature series “Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing.” He is originally from Okayama City.

Keywords

Survey of Victims of the Atomic Bombing

Hiroshima City government’s survey started in fiscal 1979, 34 years after the atomic bombing, at a time when momentum had increased for the government to clearly identify the extent of devastation caused by the atomic bombing. Using multiple documents of the national and local governments as sources, including a city register with the names of A-bomb victims housed in a stone chest beneath the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, which was erected in 1952, as well as lists of A-bomb victims belonging to companies and schools as of 1945, the survey continues to collect the names of A-bomb survivors and deceased victims.

RECNA, Nagasaki University, and the Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims have worked jointly on an online project of digitization to communicate the reality of the atomic bombing. The two pillars of the effort are the creation of an online map that utilizes aerial photos taken before and after the atomic bombing, and the development of digital content that makes use of photos featuring the daily lives of people prior to the atomic bombing.

As for the online map, we are now in the process of connecting together 121 aerial photos taken before and after the atomic bombing by the U.S. military of Nagasaki City to create a single map. Once completed, the map will be made available on the internet, enabling viewers to see how the cityscapes appeared before they were turned into ruins.

Place names frequently make their appearance when A-bomb survivors share their experiences in the atomic bombing, but listeners who might not be familiar with such places have a hard time understanding. In our plan, three-dimensional, large-scale A-bomb remnants such as Urakami Cathedral will be recreated on the map, added to which will be such information as photos, place names, and survivors’ testimonies. We are also considering having the survivors use the map when recounting their A-bombing experiences.

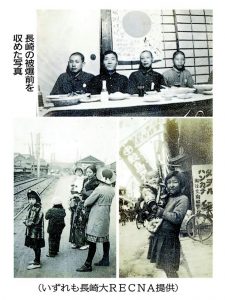

We began collecting photos depicting the everyday life of citizens before the atomic bombing at the end of July last year, and since then more than 6,000 photos have been collected from 20 individuals. The photos communicate stories about the cityscapes and people’s lives that were lost in the atomic bombing. Public organizations in Nagasaki have not been able to sufficiently gather such photos to this point in time.

Nuclear weapons cause far more damage than what is imaginable. That is why it is hard to recognize such devastation as something that actually happened or relate it to our own circumstances. After listening to survivors’ testimonies, quite a few students have said that the stories sounded like a movie because they had not had enough chances to fully imagine the deceased as human beings or the lives of the victims.

The photos can force us to imagine what nuclear weapons steal from people. For example, with a photo depicting a dinner table with a child, we can find common ground between that and our own situation. Our students have provided us with feedback that includes their ability to feel empathy rather than simply looking at a photo of ruins, and that they started to wonder about what would have happened had their own family experienced the atomic bombing. I believe that the striving to fill voids involving the A-bombing devastation is an act to recover that specific reality.

Moreover, when we experimentally colorized some of the photos with artificial intelligence (AI) technology, we obtained even more favorable responses to the photos. The method does not reproduce actual colors, and it could lead viewers to mistakenly assume that color photos existed at the time. Nonetheless, we hope to make use of the technology in keeping with the situation.

We are now busy producing videos and slides based on the collected photos. The materials, which we intend to release on the internet this fall, will likely be used in educational settings.

The average age of A-bomb survivors now exceeds 84 years. We are entering a phase in which we will be forced to tell the survivors’ stories on their behalf despite the fact that we ourselves did not experience the atomic bombing. For that reason, we must consider how much heretofore unknown reality we can uncover and preserve. In this current era in which online communication and learning have become common practice, it is important for us to have the awareness to create and develop an online learning environment.

Mitsuhiro Hayashida

Dropped out from the doctoral program at Meiji Gakuin University. Before assuming his current position in 2021, Mr. Hayashida served as leader of the drive to collect signatures for the Hibakusha Appeal. He is originally from Nagasaki City.

Because the use of nuclear weapons is now seen as a real possibility due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I think the A-bomb survivors’ recounting of their stories carries more weight.

A-bomb survivors have communicated their experiences in the form of testimonies to people in Japan and overseas, and in the course of things engendered a campaign seeking the elimination of nuclear weapons. In June, the First Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was held. In the process of establishing the treaty, the inhumanity of nuclear weapons use was highlighted. A-bomb survivors’ accounts of their experiences can therefore be said to have played a significant role.

Meanwhile, there is still more A-bombing devastation that has never been explained to this point. Testimonies, one of the forms that survivors use to share their stories, are provided to the public as presentations for such occasions as school trips and peace-education programs. Since survivors are able to speak at a venue that has been specifically set aside for them, many people at the same time have the opportunity to listen.

While survivors repeat their stories within a limited amount of time, they are prone to follow a certain type of storytelling. Despite the fact that the A-bombing devastation continues to affect the rest of their lives after the atomic bombing, survivors tend to concentrate on describing details of the devastation immediately following the A-bomb’s detonation.

Some things are not covered in the testimonies. Furthermore, only a small number of all A-bomb survivors communicate their A-bombing experiences at that time. For someone to speak about something that has left such psychological trauma can be emotionally difficult.

In particular, roadblocks exist for those on the periphery of society—namely A-bombing survivors from Korea or Japan’s feudal outcast group known as burakumin and people with disabilities—to tell their stories. I looked into personal written accounts of the experiences of hearing-impaired A-bomb survivors in Nagasaki and found that they described their plight using language indicative of their feelings of being forgotten. Many of those accounts were published in the 1980s, but A-bomb survivors had already begun to speak out about their experiences in the 1960s. Numerous books of collections of A-bomb survivor testimonies were published in the 1970s. There is a time lag among the different A-bomb survivor testimonies due to the silence imposed on the hearing impaired.

It is difficult to accurately grasp the reality of the A-bombing devastation suffered by hearing-impaired people. Many seem to live in isolation with no information about them documented in public records. Their suffering has not been actively unveiled or communicated to this point in time. That situation is indicative of the time lag that hearing-impaired survivors faced with respect to any understanding of their situation. One such individual first became aware of the term “mushroom cloud” in the 1980s.

I am communicating orally here. The majority of people here can hear me. In most cases, stories of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing have been told using speech. It is a history of the hearing-abled. The reason for the voids in the understanding of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing is not simply due to the extent of the damage. I wonder whether our societal structure itself might have caused such voids.

Turning our focus to unspoken matters can lead us to consider our own position at the present time. It is necessary to review the framework of A-bomb survivors’ testimonies and further enhance the sharing of the A-bombing devastation. That act in my view would be akin to passing on A-bomb survivors’ experiences and would result in creating a society that is more comfortable for everyone.

Chie Shijo

Graduated from the first department of literature at Waseda University. Ms. Shijo obtained her doctoral degree from the graduate school at Kyushu University (school of social and cultural studies). Before assuming her current position in 2021, she served in such posts as visiting researcher at Nagasaki University.

Discussion

A discussion among the speakers then followed concerning the intrinsic challenges facing the effort to fill the “voids” in information about the devastation caused by the atomic bombings. The session was moderated by Hibiki Yamaguchi, visiting researcher at RECNA, Nagasaki University.

Yamaguchi:

The three speakers’ reports touched on the varied voids involving Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but it seems Hiroshima is ahead of Nagasaki regarding efforts to fill such voids.

Mizukawa:

Close collaboration developed among the public, researchers, governments, and media likely played a major role. For example, the Hypocenter Reconstruction Survey, which was used as a basis for the city’s survey of A-bomb victims, was jointly carried out by the Research Institute for Radiation Biology at Hiroshima University and the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK). If the university’s research institute had performed the survey on its own, the numbers of residents it could encourage to participate in the survey would have been limited. The Chugoku Shimbun has made a variety of efforts as well.

Yamaguchi:

In 1977, Hiroshima and Nagasaki held an international symposium on the realities of the atomic bombings, their aftermath, and the actual circumstances of A-bomb survivors (a gathering involving issues related to the atomic bombings), which led to reporting and communicating of the A-bombing devastation to the United Nations Special Session on Disarmament the following year. Now, it seems that there is insufficient energy to connect voices from the A-bombed cities to the international disarmament process.

Mizukawa:

When the exhibits at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum were fully renovated several years ago, the museum primarily used the publication Hiroshima/Nagasaki no Genbaku Saigai (in English, ‘A-bombing disasters in Hiroshima and Nagasaki’), published about 40 years ago in 1979, as reference material. The two A-bombed cities should join together to create new momentum toward realization of the publication of a white paper on the atomic bombings based on new understanding about the situation. Grasping the reality of the devastation caused by the atomic bombings would lead to discussions of nuclear weapons as an issue of relevance today. We need to call on Japan’s national government, which underestimates the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons, to bear responsibility by utilizing such information.

Yamaguchi:

As for the Nagasaki program in which aerial photos are utilized, the risk might exist of internalizing the viewpoint of the side that dropped the atomic bombs.

Hayashida:

That’s exactly the issue we are discussing now. It should never generate a sense of flying on an aircraft and viewing the ground from a vantage point above the mushroom cloud. On the other hand, because the atomic bombing wrought extensive damage exceeding what is in our power to imagine, we hope to benefit from technological advances. We will continue to try and understand and work through the concerns involved.

Yamaguchi:

The period before and during the war in Nagasaki was in actual fact the days of the Pacific War and colonialism. Might there not be fears that the photos taken before the atomic bombing could give viewers an incorrect impression that people in the photos were robbed of their joyful existence after the atomic bombs were suddenly dropped one day?

Hayashida:

If the atomic bombing were discussed without touching on Japan’s role as perpetrator during the war, students would not accept such an awkward situation. Not repeating war will ultimately lead to atomic bombs not being used. We will incorporate this message into our project.

Yamaguchi:

I want to understand the background behind why activities to interview hearing-impaired survivors in Nagasaki and transcribe their stories weren’t carried out until the 1980s.

Shijo:

Testimonies by A-bomb survivors gathered steam starting in the 1960s. Images drawn by A-bomb survivors began to appear in the 1970s. During the period immediately after the war, the psychological and physical scars were still very raw among the people. They struggled simply to continue to live. Under such circumstances, an additional time lag arose for the hearing-impaired survivors. The issue with their linguistic skills might have been part of the reason for the lag. During the war, such individuals were unable to fully attend special schools for the hearing-impaired, and even if they did attend, they might have been unable to gain sufficient language skills. Their A-bombing experiences came to light for first time with the help of sign-language interpreters.

Even with the current framework of taking on A-bomb survivors’ experiences and passing the information to future generations, some aspects of that story are relatively difficult to focus on. Consideration of such voids requires consistent effort, the antithesis of easy understanding. I believe it is important to adopt a comprehensive approach to documenting the wide variety of A-bombing devastation that includes details that have been lost along the way.

Yamaguchi:

Mr. Mizukawa, what was the most difficult part in doing the reporting for your articles? I’d also like to know what other types of reporting you are planning.

Mizukawa:

With the A-bomb victims survey being carried out by the Hiroshima City government, places other than the Hiroshima could hold many clues about things we don’t currently understand. For example, I once took a plane to Ishigaki Island in Okinawa Prefecture to meet a family that appeared to have been close relatives of a certain unclaimed A-bomb victim, based on the victim’s name in the list of unclaimed remains housed in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound. Ultimately, however, I found they were not the family of the victim. Naturally, many A-bomb survivors died in 1946 and thereafter. I also want to do more reporting to fill any of the voids that might exist from the several years after the end of 1945.

Yamaguchi:

Mr. Hayashida, what are you most aware of when someone like you, who hasn’t experienced the atomic bombing, communicates A-bomb survivor accounts to young people?

Hayashida:

I am always conscious of the fact that I have continued this activity not because I am a third-generation A-bomb survivor. Imagining what would result if this were to happen again, I became angry and set out to work on the issue with A-bomb survivors. When I communicate such accounts, I am not simply representing survivors but am speaking as myself.

Another point is that the context of war and the context of A-bombing devastation tend to be communicated separately, with a structure in place that makes it difficult to pay attention to the question of why such a war happened in the first place. The atomic bomb was dropped during the war. That is why the A-bombing devastation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki is not understood by people throughout the world in the same way we have been able to understand it. I am always conscious of positioning the atomic bombings within the broader war itself.

Yamaguchi:

In according with the A-bombed cities’ activities to fill such voids, what can be said about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

Shijo:

The scars left by the atomic bombings are different depending on not only the distance from the hypocenter for the victims but also their social status. Similar to the situation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not all Ukrainians are the same. People are placed in various situations in Ukraine and there is trauma about which not much is spoken. Such a situation continues today and will continue even after the war ends. If we can imagine people in different social circumstances than our own, I believe we can form connections with each other.

Keywords

Hypocenter Reconstruction Survey

A survey led by the late Kiyoshi Shimizu, professor at Hiroshima University, that was conducted starting in the late 1960s with the aim of reproducing the Hiroshima cityscapes in the hypocenter area that were annihilated in the atomic bombing and creating a map of all the area’s residences based on the involvement of former residents of the area. The circumstances of the damage to each house and household were documented in detail. Based on data obtained through the survey, the Hiroshima City government initiated its survey of A-bomb victims.

As part of a program commemorating the 130th anniversary of the Chugoku Shimbun’s founding, a video of actress Sayuri Yoshinaga reading A-bomb poems was aired. Ms. Yoshinaga emotionally read aloud three poems: “Jo” (in English, ‘Preface’) from Sankichi Toge’s Genbaku Shishu (in English, ‘Poems of the Bomb’), “Dokoku” (’Weeping’) by Kazuko Ohira, and “Orizuru” (‘Paper Crane’) by Sadako Kurihara.

With support from the Hiroshima International Cultural Foundation, Ms. Yoshinaga’s video was recorded in advance at a studio in Tokyo in late June. As the number of people who directly experienced the devastation of the atomic bombings declines with the passage of time, we need to think about how to handle their words and pass them on to future generations from the perspective of people not actually affected by the bombings. Her readings gave everyone an opportunity to think together about that imperative.

Ms. Yoshinaga said she first became aware of the scars caused by the atomic bombing when she visited Hiroshima for the filming of the movie “The Heart of Hiroshima” (released in 1966). She has continued the reading of A-bomb poems as part of her lifework, which includes her role as a geisha that experienced the atomic bombing while in her mother’s womb in the NHK television drama series titled “Yumechiyo Nikki” (in English, ‘Yumechiyo’s diary’), first broadcast in 1981. In 1997, she released a compact disk titled “Second Movement” that contained her readings of 12 A-bomb poems.

In an interview held after the recording, Ms. Yoshinaga spoke of the situation in Ukraine, which has been torn asunder by war after Russia’s military’s invasion, and about the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), connected to which the first states parties meeting was held last month, and stressed her feeling that “the present is a most crucial time.”

As for Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who was elected as a representative of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima and advocates “a world without nuclear weapons,” Ms. Yoshinaga said, “Mr. Kishida is a relative of Setsuko Thurlow [A-bomb survivor who lives in Canada], who made great contributions to realization of the treaty. I really wanted his government to participate in the states parties meeting even if it were as an observer.”

On the subject of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s comment threatening the use of nuclear weapons, she said, “Looking at the current state of things, I think everyone feels as if the situation is risky and that something must be done to stop it.” She also spoke of her determination that every single citizen, not only politicians, must act proactively to achieve the goal of elimination of nuclear weapons.

(Originally published on July 26, 2022)

On July 18, the Hiroshima Peace Institute (HPI), Hiroshima City University, the Chugoku Shimbun, and the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) at Nagasaki University jointly held an online symposium titled Memories of War: Striving to Fill Voids in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Regarding the actual condition of the atomic bombings that annihilated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, many missing pieces of the puzzle remain because of the extent of destruction, and the Japan national government’s consistent attitude of avoiding identification of the actual devastation through a full-fledged survey even after the war ended. As 77 years has passed since August 6, 1945, and with aging of atomic bomb survivors, this Chugoku Shimbun staff writer and university researchers discussed at the symposium current challenges in this effort. A total of about 300 people viewed the livestreamed symposium in screening venues located in the Chugoku Shimbun Hall and other places.

Speakers

Reports and Discussion

Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer, the Chugoku Shimbun

Mitsuhiro Hayashida, Project Researcher, RECNA, Nagasaki University

Chie Shijo, Associate Professor, HPI, Hiroshima City University

Moderator

Hibiki Yamaguchi, Visiting Researcher and Program-Specific Professor, RECNA, Nagasaki University

Emcee

Makiko Takemoto, Associate Professor, HPI, Hiroshima City University

Kyosuke Mizukawa

Victims’ remains returned to bereaved family through publicly disclosed information

More materials need to be found and checked for city survey of A-bomb victims

The average age of A-bomb survivors exceeded 84 years this year. As those who continue to communicate their A-bombing experiences grow older, a diversity of activities has been broadly undertaken to pass on their A-bombing memories to future generations. Meanwhile, “voids” remain involving information about the actual devastation wrought by the atomic bombings that are not understood to this day. How such unknown areas of the devastation should be examined and placed on record is being put to the test.

The Chugoku Shimbun lost 114 employees in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. In an editorial written in 1964, the news company advocated the idea of looking at the horror of the atomic bombing in detail and conveying it to the world. Former staff writers at the Chugoku Shimbun uncovered devastation that had been buried. With their efforts in mind, in 2019 the Chugoku Shimbun began the series of articles titled “Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima,” which received the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association Award for fiscal 2020.

One of the series’ pillars relates to voids in the A-bombing death toll. A written request that the Hiroshima and Nagasaki City governments submitted to the United Nations in 1976 reported that the number of deaths related to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by the end of 1945 was estimated to be 140,000 (±10,000). On the other hand, a city government survey of victims of the atomic bombing that began in 1979 showed the death toll by the end of 1945 to be 89,025, as of March 2019.

Put simply, those two figures are separated by a gap of several tens of thousands of people. After a closer look, we confirmed that the government survey faced difficulties in identifying some categories of deceased, such as those in a household whose members all died in the bombing, military personnel dispatched from outside Hiroshima Prefecture, and people who were from the Korean Peninsula. One of the background factors was the national government’s passive attitude with respect to the survey investigating the entire picture of victims. Because some materials kept outside of Hiroshima Prefecture or overseas have not been used in the survey, their active utilization is now necessary.

We also reported on the remains of victims. It is said the remains of about 70,000 unclaimed victims are stored in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, with the names of 814 of such victims identified to date. The city lists the names of the unclaimed remains as it searches for bereaved family members, but Japan’s national government is not involved in such an effort, based on its idea that such work is the responsibility of local governments.

Our newspaper team then went about searching for surviving family members of victims. When the names on the city’s list were checked against the names of victims registered by their families at the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, some names with matching pronunciation and addresses were found. The work ended up with the return of some victims’ remains to family members. In another example, I found a personal note written by someone whose family name was the same as that of an unclaimed victim, leading finally to confirmation of that victim’s identity. There are things we can do with publicly disclosed information.

Moreover, the Chugoku Shimbun’s printed edition and website have introduced photographs taken in Hiroshima before the atomic bombing under the title “Recreating cityscapes.” The public-sector system whereby pre-bombing period photos are collected is insufficient. By asking our readers to seek out and provide us with relevant materials, we have received photos that escaped destruction by the fires that arose immediately after the atomic bombing from about 70 individuals and organizations. Now, about 1,200 photos with the locations at which they were taken being specified have been released to the public, conveying images of cityscapes erased in the atomic bombing.

While our team has traced the lives of victims and identified remains that had been missed in the city’s survey of A-bomb victims over such a long period, we were able to get a sense of the impact of each individual’s life. By continuously reporting victims’ records with that in mind, I believe we can clearly reveal the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons use.

Kyosuke Mizukawa

Graduated from the Faculty of Letters at the University of Tokyo and joined the Chugoku Shimbun in 2007. Before taking his current post, Mr. Mizukawa worked for the company’s news division and the Bingo area branch office. He also penned articles for the feature series “Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing.” He is originally from Okayama City.

Keywords

Survey of Victims of the Atomic Bombing

Hiroshima City government’s survey started in fiscal 1979, 34 years after the atomic bombing, at a time when momentum had increased for the government to clearly identify the extent of devastation caused by the atomic bombing. Using multiple documents of the national and local governments as sources, including a city register with the names of A-bomb victims housed in a stone chest beneath the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, which was erected in 1952, as well as lists of A-bomb victims belonging to companies and schools as of 1945, the survey continues to collect the names of A-bomb survivors and deceased victims.

Mitsuhiro Hayashida

Utilization of photos of daily life in pre-bombing period bring back reality of those times

RECNA, Nagasaki University, and the Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims have worked jointly on an online project of digitization to communicate the reality of the atomic bombing. The two pillars of the effort are the creation of an online map that utilizes aerial photos taken before and after the atomic bombing, and the development of digital content that makes use of photos featuring the daily lives of people prior to the atomic bombing.

As for the online map, we are now in the process of connecting together 121 aerial photos taken before and after the atomic bombing by the U.S. military of Nagasaki City to create a single map. Once completed, the map will be made available on the internet, enabling viewers to see how the cityscapes appeared before they were turned into ruins.

Place names frequently make their appearance when A-bomb survivors share their experiences in the atomic bombing, but listeners who might not be familiar with such places have a hard time understanding. In our plan, three-dimensional, large-scale A-bomb remnants such as Urakami Cathedral will be recreated on the map, added to which will be such information as photos, place names, and survivors’ testimonies. We are also considering having the survivors use the map when recounting their A-bombing experiences.

We began collecting photos depicting the everyday life of citizens before the atomic bombing at the end of July last year, and since then more than 6,000 photos have been collected from 20 individuals. The photos communicate stories about the cityscapes and people’s lives that were lost in the atomic bombing. Public organizations in Nagasaki have not been able to sufficiently gather such photos to this point in time.

Nuclear weapons cause far more damage than what is imaginable. That is why it is hard to recognize such devastation as something that actually happened or relate it to our own circumstances. After listening to survivors’ testimonies, quite a few students have said that the stories sounded like a movie because they had not had enough chances to fully imagine the deceased as human beings or the lives of the victims.

The photos can force us to imagine what nuclear weapons steal from people. For example, with a photo depicting a dinner table with a child, we can find common ground between that and our own situation. Our students have provided us with feedback that includes their ability to feel empathy rather than simply looking at a photo of ruins, and that they started to wonder about what would have happened had their own family experienced the atomic bombing. I believe that the striving to fill voids involving the A-bombing devastation is an act to recover that specific reality.

Moreover, when we experimentally colorized some of the photos with artificial intelligence (AI) technology, we obtained even more favorable responses to the photos. The method does not reproduce actual colors, and it could lead viewers to mistakenly assume that color photos existed at the time. Nonetheless, we hope to make use of the technology in keeping with the situation.

We are now busy producing videos and slides based on the collected photos. The materials, which we intend to release on the internet this fall, will likely be used in educational settings.

The average age of A-bomb survivors now exceeds 84 years. We are entering a phase in which we will be forced to tell the survivors’ stories on their behalf despite the fact that we ourselves did not experience the atomic bombing. For that reason, we must consider how much heretofore unknown reality we can uncover and preserve. In this current era in which online communication and learning have become common practice, it is important for us to have the awareness to create and develop an online learning environment.

Mitsuhiro Hayashida

Dropped out from the doctoral program at Meiji Gakuin University. Before assuming his current position in 2021, Mr. Hayashida served as leader of the drive to collect signatures for the Hibakusha Appeal. He is originally from Nagasaki City.

Chie Shijo

Shifting focus to unspoken things, shedding light on testimonies from hearing-impaired A-bomb survivors

Because the use of nuclear weapons is now seen as a real possibility due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I think the A-bomb survivors’ recounting of their stories carries more weight.

A-bomb survivors have communicated their experiences in the form of testimonies to people in Japan and overseas, and in the course of things engendered a campaign seeking the elimination of nuclear weapons. In June, the First Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was held. In the process of establishing the treaty, the inhumanity of nuclear weapons use was highlighted. A-bomb survivors’ accounts of their experiences can therefore be said to have played a significant role.

Meanwhile, there is still more A-bombing devastation that has never been explained to this point. Testimonies, one of the forms that survivors use to share their stories, are provided to the public as presentations for such occasions as school trips and peace-education programs. Since survivors are able to speak at a venue that has been specifically set aside for them, many people at the same time have the opportunity to listen.

While survivors repeat their stories within a limited amount of time, they are prone to follow a certain type of storytelling. Despite the fact that the A-bombing devastation continues to affect the rest of their lives after the atomic bombing, survivors tend to concentrate on describing details of the devastation immediately following the A-bomb’s detonation.

Some things are not covered in the testimonies. Furthermore, only a small number of all A-bomb survivors communicate their A-bombing experiences at that time. For someone to speak about something that has left such psychological trauma can be emotionally difficult.

In particular, roadblocks exist for those on the periphery of society—namely A-bombing survivors from Korea or Japan’s feudal outcast group known as burakumin and people with disabilities—to tell their stories. I looked into personal written accounts of the experiences of hearing-impaired A-bomb survivors in Nagasaki and found that they described their plight using language indicative of their feelings of being forgotten. Many of those accounts were published in the 1980s, but A-bomb survivors had already begun to speak out about their experiences in the 1960s. Numerous books of collections of A-bomb survivor testimonies were published in the 1970s. There is a time lag among the different A-bomb survivor testimonies due to the silence imposed on the hearing impaired.

It is difficult to accurately grasp the reality of the A-bombing devastation suffered by hearing-impaired people. Many seem to live in isolation with no information about them documented in public records. Their suffering has not been actively unveiled or communicated to this point in time. That situation is indicative of the time lag that hearing-impaired survivors faced with respect to any understanding of their situation. One such individual first became aware of the term “mushroom cloud” in the 1980s.

I am communicating orally here. The majority of people here can hear me. In most cases, stories of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing have been told using speech. It is a history of the hearing-abled. The reason for the voids in the understanding of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing is not simply due to the extent of the damage. I wonder whether our societal structure itself might have caused such voids.

Turning our focus to unspoken matters can lead us to consider our own position at the present time. It is necessary to review the framework of A-bomb survivors’ testimonies and further enhance the sharing of the A-bombing devastation. That act in my view would be akin to passing on A-bomb survivors’ experiences and would result in creating a society that is more comfortable for everyone.

Chie Shijo

Graduated from the first department of literature at Waseda University. Ms. Shijo obtained her doctoral degree from the graduate school at Kyushu University (school of social and cultural studies). Before assuming her current position in 2021, she served in such posts as visiting researcher at Nagasaki University.

Discussion

A discussion among the speakers then followed concerning the intrinsic challenges facing the effort to fill the “voids” in information about the devastation caused by the atomic bombings. The session was moderated by Hibiki Yamaguchi, visiting researcher at RECNA, Nagasaki University.

Yamaguchi:

The three speakers’ reports touched on the varied voids involving Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but it seems Hiroshima is ahead of Nagasaki regarding efforts to fill such voids.

Mizukawa:

Close collaboration developed among the public, researchers, governments, and media likely played a major role. For example, the Hypocenter Reconstruction Survey, which was used as a basis for the city’s survey of A-bomb victims, was jointly carried out by the Research Institute for Radiation Biology at Hiroshima University and the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK). If the university’s research institute had performed the survey on its own, the numbers of residents it could encourage to participate in the survey would have been limited. The Chugoku Shimbun has made a variety of efforts as well.

Yamaguchi:

In 1977, Hiroshima and Nagasaki held an international symposium on the realities of the atomic bombings, their aftermath, and the actual circumstances of A-bomb survivors (a gathering involving issues related to the atomic bombings), which led to reporting and communicating of the A-bombing devastation to the United Nations Special Session on Disarmament the following year. Now, it seems that there is insufficient energy to connect voices from the A-bombed cities to the international disarmament process.

A-bombed cities should collaborate to seek new knowledge

Mizukawa:

When the exhibits at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum were fully renovated several years ago, the museum primarily used the publication Hiroshima/Nagasaki no Genbaku Saigai (in English, ‘A-bombing disasters in Hiroshima and Nagasaki’), published about 40 years ago in 1979, as reference material. The two A-bombed cities should join together to create new momentum toward realization of the publication of a white paper on the atomic bombings based on new understanding about the situation. Grasping the reality of the devastation caused by the atomic bombings would lead to discussions of nuclear weapons as an issue of relevance today. We need to call on Japan’s national government, which underestimates the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons, to bear responsibility by utilizing such information.

Yamaguchi:

As for the Nagasaki program in which aerial photos are utilized, the risk might exist of internalizing the viewpoint of the side that dropped the atomic bombs.

Hayashida:

That’s exactly the issue we are discussing now. It should never generate a sense of flying on an aircraft and viewing the ground from a vantage point above the mushroom cloud. On the other hand, because the atomic bombing wrought extensive damage exceeding what is in our power to imagine, we hope to benefit from technological advances. We will continue to try and understand and work through the concerns involved.

Yamaguchi:

The period before and during the war in Nagasaki was in actual fact the days of the Pacific War and colonialism. Might there not be fears that the photos taken before the atomic bombing could give viewers an incorrect impression that people in the photos were robbed of their joyful existence after the atomic bombs were suddenly dropped one day?

Japan’s role as perpetrator must not be forgotten

Hayashida:

If the atomic bombing were discussed without touching on Japan’s role as perpetrator during the war, students would not accept such an awkward situation. Not repeating war will ultimately lead to atomic bombs not being used. We will incorporate this message into our project.

Yamaguchi:

I want to understand the background behind why activities to interview hearing-impaired survivors in Nagasaki and transcribe their stories weren’t carried out until the 1980s.

Shijo:

Testimonies by A-bomb survivors gathered steam starting in the 1960s. Images drawn by A-bomb survivors began to appear in the 1970s. During the period immediately after the war, the psychological and physical scars were still very raw among the people. They struggled simply to continue to live. Under such circumstances, an additional time lag arose for the hearing-impaired survivors. The issue with their linguistic skills might have been part of the reason for the lag. During the war, such individuals were unable to fully attend special schools for the hearing-impaired, and even if they did attend, they might have been unable to gain sufficient language skills. Their A-bombing experiences came to light for first time with the help of sign-language interpreters.

Even with the current framework of taking on A-bomb survivors’ experiences and passing the information to future generations, some aspects of that story are relatively difficult to focus on. Consideration of such voids requires consistent effort, the antithesis of easy understanding. I believe it is important to adopt a comprehensive approach to documenting the wide variety of A-bombing devastation that includes details that have been lost along the way.

Yamaguchi:

Mr. Mizukawa, what was the most difficult part in doing the reporting for your articles? I’d also like to know what other types of reporting you are planning.

Mizukawa:

With the A-bomb victims survey being carried out by the Hiroshima City government, places other than the Hiroshima could hold many clues about things we don’t currently understand. For example, I once took a plane to Ishigaki Island in Okinawa Prefecture to meet a family that appeared to have been close relatives of a certain unclaimed A-bomb victim, based on the victim’s name in the list of unclaimed remains housed in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound. Ultimately, however, I found they were not the family of the victim. Naturally, many A-bomb survivors died in 1946 and thereafter. I also want to do more reporting to fill any of the voids that might exist from the several years after the end of 1945.

Yamaguchi:

Mr. Hayashida, what are you most aware of when someone like you, who hasn’t experienced the atomic bombing, communicates A-bomb survivor accounts to young people?

Hayashida:

I am always conscious of the fact that I have continued this activity not because I am a third-generation A-bomb survivor. Imagining what would result if this were to happen again, I became angry and set out to work on the issue with A-bomb survivors. When I communicate such accounts, I am not simply representing survivors but am speaking as myself.

Another point is that the context of war and the context of A-bombing devastation tend to be communicated separately, with a structure in place that makes it difficult to pay attention to the question of why such a war happened in the first place. The atomic bomb was dropped during the war. That is why the A-bombing devastation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki is not understood by people throughout the world in the same way we have been able to understand it. I am always conscious of positioning the atomic bombings within the broader war itself.

Imagining people’s circumstances in different societies

Yamaguchi:

In according with the A-bombed cities’ activities to fill such voids, what can be said about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

Shijo:

The scars left by the atomic bombings are different depending on not only the distance from the hypocenter for the victims but also their social status. Similar to the situation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not all Ukrainians are the same. People are placed in various situations in Ukraine and there is trauma about which not much is spoken. Such a situation continues today and will continue even after the war ends. If we can imagine people in different social circumstances than our own, I believe we can form connections with each other.

Keywords

Hypocenter Reconstruction Survey

A survey led by the late Kiyoshi Shimizu, professor at Hiroshima University, that was conducted starting in the late 1960s with the aim of reproducing the Hiroshima cityscapes in the hypocenter area that were annihilated in the atomic bombing and creating a map of all the area’s residences based on the involvement of former residents of the area. The circumstances of the damage to each house and household were documented in detail. Based on data obtained through the survey, the Hiroshima City government initiated its survey of A-bomb victims.

Actress Sayuri Yoshinaga reads A-bomb poems with feeling in video

As part of a program commemorating the 130th anniversary of the Chugoku Shimbun’s founding, a video of actress Sayuri Yoshinaga reading A-bomb poems was aired. Ms. Yoshinaga emotionally read aloud three poems: “Jo” (in English, ‘Preface’) from Sankichi Toge’s Genbaku Shishu (in English, ‘Poems of the Bomb’), “Dokoku” (’Weeping’) by Kazuko Ohira, and “Orizuru” (‘Paper Crane’) by Sadako Kurihara.

With support from the Hiroshima International Cultural Foundation, Ms. Yoshinaga’s video was recorded in advance at a studio in Tokyo in late June. As the number of people who directly experienced the devastation of the atomic bombings declines with the passage of time, we need to think about how to handle their words and pass them on to future generations from the perspective of people not actually affected by the bombings. Her readings gave everyone an opportunity to think together about that imperative.

Ms. Yoshinaga said she first became aware of the scars caused by the atomic bombing when she visited Hiroshima for the filming of the movie “The Heart of Hiroshima” (released in 1966). She has continued the reading of A-bomb poems as part of her lifework, which includes her role as a geisha that experienced the atomic bombing while in her mother’s womb in the NHK television drama series titled “Yumechiyo Nikki” (in English, ‘Yumechiyo’s diary’), first broadcast in 1981. In 1997, she released a compact disk titled “Second Movement” that contained her readings of 12 A-bomb poems.

In an interview held after the recording, Ms. Yoshinaga spoke of the situation in Ukraine, which has been torn asunder by war after Russia’s military’s invasion, and about the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), connected to which the first states parties meeting was held last month, and stressed her feeling that “the present is a most crucial time.”

As for Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who was elected as a representative of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima and advocates “a world without nuclear weapons,” Ms. Yoshinaga said, “Mr. Kishida is a relative of Setsuko Thurlow [A-bomb survivor who lives in Canada], who made great contributions to realization of the treaty. I really wanted his government to participate in the states parties meeting even if it were as an observer.”

On the subject of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s comment threatening the use of nuclear weapons, she said, “Looking at the current state of things, I think everyone feels as if the situation is risky and that something must be done to stop it.” She also spoke of her determination that every single citizen, not only politicians, must act proactively to achieve the goal of elimination of nuclear weapons.

(Originally published on July 26, 2022)