Family memories 77 years after A-bombing, Part 5: Wish for reunion with long-missing brother fails to be realized

Jul. 31, 2022

Able to “reunite” with deceased brother through personal notes

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

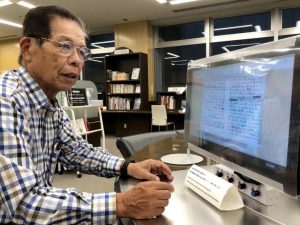

In late June, Toshiaki Moriyasu, 77, a resident of Joyo City in Kyoto Prefecture, stared at handwritten notes of a personal atomic bombing experience that appeared on a monitor in the reading room of the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, located within Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the city’s Naka Ward. Mr. Moriyasu remarked, “So, those are the notes written by my older brother?” And thus marked a “reunion” of sorts with his older brother, Masaaki, from whom he had become separated after the war and whose face he had encountered for the first time in 77 years. Masaaki was 19 years old at the time of the bombing.

Desperate wish

Everything started with a letter that Mr. Moriyasu sent to the Chugoku Shimbun. In the letter he wrote, “Would you help me locate my older brother?” In the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, he had lost his father, Yukai Moriyasu, and had become separated from his older brother. He described a desperate wish in the letter. “I don’t think I will that live that long, and I want to see my older brother while I’m still alive.”

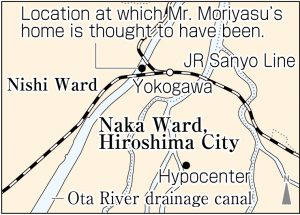

According to Mr. Moriyasu, four members of his family lived in Uchikoshi-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward), an area near the present-day JR Yokogawa Station. At the instant of the atomic bombing, Mr. Moriyasu was a five-month-old infant, and his mother, Ayano, immediately threw herself over him to protect his body. Following the end of the war, Mr. Moriyasu and his mother moved to her hometown, located in what is now part of Kurashiki City in Okayama Prefecture, but his older brother appears to have stayed behind in Hiroshima.

Until she died in 1978, his mother refused to talk at all about his father or older brother. As for why he asked for help in finding his brother from the Chugoku Shimbun, Hiroshima’s local newspaper, he had written, “Because I only know that my father died in the atomic bombing and that I had an older brother.”

Nevertheless, his hope for a reunion soon collapsed. Motivated by having sent the letter to the Chugoku Shimbun, he took it upon himself to once again examine documents related to his family register and found that Masaaki had died in 2020. He then hoped, at the very least, to meet his brother’s surviving family. Based on that wish by the disheartened Mr. Moriyasu, this writer continued the search.

The clues were limited, however. The configuration of the Uchikoshi-cho area has changed greatly since development of the Ota River drainage canal. When a lot number of his family’s former address was investigated using both new and old maps, it was found that the lot is now part of the drainage canal. This writer continued to gather information and in June of this year was finally able to come in contact with a member of Masaaki’s family who was living in Hiroshima.

The family member accepted my sudden visit, but the gap of 77 years proved too long. They said, “I’ve never heard anything about him [Masaaki] having a younger brother.” In terms of any meeting with Mr. Moriyasu, they politely rejected the offer, saying, “I’m afraid it has taken so much time. Even if we were to meet him, I don’t think there would be anything we could talk about.”

Regret

After listening to the entire story from this writer, Mr. Moriyasu said, “I probably was too slow to act.” The sigh he emitted was symbolic of his deep regret. He had attended a university in Kyoto from his home of Kurashiki. After graduating from the school, he started work at a financial institution. He worked so hard that he barely had time to return home. When he finally came to wonder whether it was acceptable for him to be ignorant of his brother, he was well into his retirement years.

He was able to learn information about how his family members had experienced the atomic bombing because Masaaki had submitted written notes about his personal A-bombing story in response to a fact-finding survey of A-bomb survivors conducted by Japan’s former Ministry of Health and Welfare in 1995.

Masaaki experienced the atomic bombing in the area of Uchikoshi-cho and continued to walk around in search of his father, who had not returned home. He wrote, “There were many dead bodies on the ground. It was hard to imagine they had been human. I managed to move forward by stepping over people.” When he paid another visit to the Homare aircraft factory, in the area of Kusunoki-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward), where Mr. Moriyasu’s father was assumed to be, Masaaki found his father dead under a collapsed warehouse.

In his brother’s notes, replete with traces of rewritten parts, he described how he and his neighbors had cooperated with each other and lived in shacks, and that he feared effects from having experienced the atomic bombing, information that came to light only gradually after the bombing. Mr. Moriyasu said, “I was grateful I could understand a little bit of what went on at that time.” These are the A-bombing memories of his family, separated by the unprecedented disaster and ultimately unable to fulfill the wish of being reunited. He confronted the record left by his brother, examining it letter by letter.

(Originally published on July 31, 2022)