Family memories 77 years after A-bombing, Part 6: Mission to convey inhumanity of nuclear weapons

Aug. 1, 2022

Keeping in mind great-grandfathers’ experiences in providing medical care

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

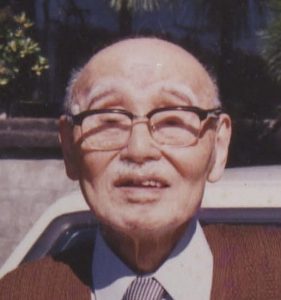

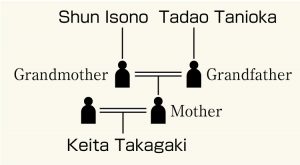

Keita Takagaki, 20, a resident of Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward who is a sophomore at Waseda University in Tokyo, attended the First Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which was held in Vienna, Austria, earlier this year in June. Mr. Takagaki said, “After giving serious thought to my great-grandfathers’ experiences, I began to consider what I myself could do.” The start of his involvement in the movement to eliminate nuclear weapons were the experiences in the atomic bombing of his two great-grandfathers, who had provided medical care to the wounded immediately after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

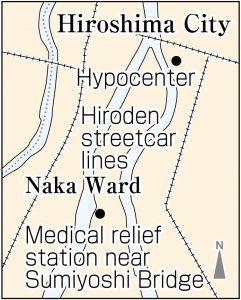

The grandparent who lived in the Hiroshima area, Tadao Tanioka, was 52 years of age at the time of the bombing. Mr. Tanioka was a physician in private practice in present-day Miyoshi City. He traveled to Hiroshima City on August 7, the day after the atomic bombing, as a member of a medical relief team made up of physicians and nurses from a local medical association. The team provided medical care to the wounded at a medical relief station near Sumiyoshi Bridge (now located in the city’s Naka Ward).

Intuiting great-grandfathers’ regrets

According to Hiroshima Genbaku Iryoushi (in English, ‘History of Hiroshima atomic bomb medical treatment’), which was published in 1961, 53 medical relief stations were temporarily set up in and around the city, including the one near Sumiyoshi Bridge. According to that historical record, 90 percent of around 300 physicians in Hiroshima experienced the bombing, increasing the importance of the role of the medical teams that rushed in from outside the city. Despite that, Mr. Takagaki said, “I understand that the medicine brought into the city ran out quickly, and they had to carefully select for treatment the patients whose lives could be saved.”

The other great-grandfather, Shun Isono, 41 at the time of the bombing, was also a physician in private practice. Mr. Isono lived in the present-day Minamishimabara in Nagasaki Prefecture and rushed to Nagasaki Medical College (now Nagasaki University School of Medicine) on August 9, the day of the atomic bombing of that city. He provided medical care in the schoolyard, but people waiting to be treated would reach their limits and die.

“As physicians, it must have been distressing for them not to be able to help the people right in front of them,” said Mr. Takagaki, sympathizing with his great-grandfathers for what they had faced at the time. He heard that they continued to accept and treat the wounded at their clinics even after returning home.

Continuing his journey

Although hearing stories about his two great-grandfathers since he was a child, it was a school speech contest when Mr. Takagaki was a third-year junior high school student that heightened his awareness. He did not have a strong consciousness about nuclear issues at the time, but he did dare to speak about their experiences. With his speech receiving particularly high marks, he won the class contest and was given an opportunity to speak in front of all students in the school. “If I keep those memories only in my mind, they will be lost someday,” he began to think. It was then that he became aware of his mission to take on his family’s A-bombing experiences and communicate those stories to others.

After entering Sotoku High School, located in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, he joined the school’s newspaper club in the middle of the school year and actively looked into the damage caused to the former Army Clothing Depot, located in the city’s Minami Ward, and to the former Sotoku Junior High School, which was the predecessor to his school. At that time, a debate was underway regarding whether or not to preserve the clothing depot buildings. During his research into the issue, he learned of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). He interviewed Regis Savioz, then head of the ICRC’s Delegation in Japan. He began to see the overlap of his great-grandfathers’ experiences and the ICRC’s call for a ban on nuclear weapons as inhumane weapons that even destroy medical infrastructures.

Upon entering university, he began work as a volunteer at the ICRC’s Delegation in Japan, based in Tokyo. While involved in event planning and other work, he was chosen as a youth representative to convey a portion of the organization’s official statement at the TPNW meeting held in June. In that statement, he referred to the devastation caused by nuclear testing and discrimination against A-bomb survivors and called for, in English, the meeting to serve as an opportunity to discover and share measures to remedy the devastation caused by nuclear weapons.

The speech was delivered on the grand stage of an international conference. “I had my great-grandfather’s Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate in the inner pocket of my suit,” said Mr. Takagaki, revealing the small notebook he had inherited. Written in the notebook was the fact that Tadao Tanioka entered Hiroshima on August 7, 1945, and had been exposed to radiation.

“I want to move forward while keeping in mind not only my great-grandfathers’ wishes but also those of the people they could not save,” he said. Mr. Tanioka continues his search for what he can do to help create a world free of nuclear weapons. Still, he said he will never lose sight of his family memories, which serve as a foothold for him.

This article concludes the series “Family memories 77 years after A-bombing.”

(Originally published on August 1, 2022)