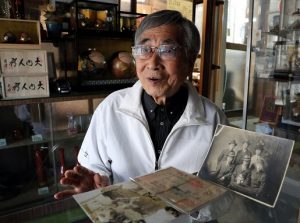

Hiroshima Voices: “No Nukes, No War” Sadao Ogasawara, 95, Ouchi lacquerware artist and A-bomb survivor, Yamaguchi City

Nov. 4, 2022

Cremated corpses, pulverized bones, and disposed of them, losing any sense they were human beings

Mr. Ogasawara cremated countless A-bomb victims' corpses at the Army Clothing Depot buildings (now located in Hiroshima's Minami Ward), where he worked and which were used as a relief station after the atomic bombing. After the war ended, he became an artist of Ouchi lacquerware, a traditional Yamaguchi Prefecture craft. Considering the Ouchi lacquerware dolls, with their kind smiling faces, to be a symbol of peace, Mr. Ogasawara uses brushes to pay his respects to such victims.

Click here to view the video

When the news about the Ukraine situation appears on television, I sometimes just turn the channel, because it reminds me of what I experienced at the time of the atomic bombing. It was a situation that is simply impossible to put into words.

On August 6, 1945, I was on a business trip to the area of Miyoshi-cho (now Miyoshi City, located in Hiroshima Prefecture) and returned to Hiroshima in the early morning of August 7, a day later. The Aioi Bridge, located near the hypocenter, was all twisted and bent. In front of the Shirakami-sha Shrine, I witnessed the corpse of a horse with its internal organs spilling out and people lying on the ground. Many injured people who were on the roadside grabbed at me, imploring me to help, a feeling that haunts me to this day. When I went back to the same place later in the afternoon, all of them had died.

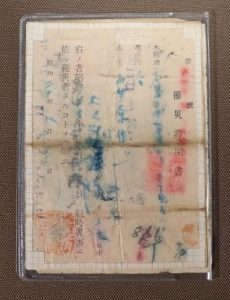

At the former Army Clothing Depot buildings, which were used as a relief station, the number of the deceased increased day by day, with the white walls turning black from all the flies that had gathered there. Outside, I threw the corpses of about 30 people into a single hole, spread gas over them, and set them ablaze. Among the victims were the corpses of children and pregnant women. Later, I pulverized their bones into pieces with a shovel and threw the pieces away in a nearby lotus pond. I had lost the sense that they were once human beings. I felt so bad about what I had to do. When victims' names were identified, we put their fingernails and hair in an envelope and posted the envelopes on one of the walls. Even then, though, as long as I was there at the depot building, until August 13, I don't think anyone came to pick up any of the envelopes.

To make a living after the end of the war, I became the apprentice of a distant relative who was working as an Ouchi lacquerware artist. It was a demanding work environment, but with the support of people around me, I was able to continue my career and engage in the peaceful work of making dolls. I want to tell Russian President Vladimir Putin that if you perform good deeds for someone, you will be repaid with kindness. At the same time, if you act in a negative manner toward someone, you will have to pay a price. I hope the negative chain reaction of history that is war can be stopped.

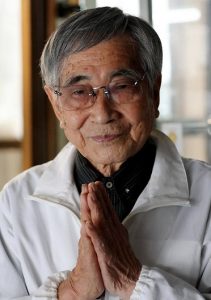

When I visit Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, in the city’s Naka Ward, I always first place my hands together in prayer in front of the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, based on the idea that the human remains I disposed of at that time might be stored in the mound. I don’t want anyone else to ever again experience what I have had to. While making Ouchi lacquerware dolls, with their kind smiling faces, all I can do is pray that the world situation settles down as soon as possible. (Interviewed by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer)