Survivors’ Stories: Hiroshi Harada, 83, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima―Fled while stepping on human bodies

Oct. 31, 2022

Working hand in hand with citizens as museum director

by Rina Yuasa, Staff Writer

Hiroshi Harada, 83, former director of the Peace Memorial Museum located in the city’s Naka Ward, was exposed to the atomic bomb when he was 6 years old at Hiroshima Station located in the city’s Minami Ward about 2 kilometers from the hypocenter. He can never forget what he experienced on that day of August 6, 1945 when he was a child. With a sense of responsibility to ensure that such a tragedy would not occur again, he devoted himself to the promotion of peace-related efforts as an official of the City of Hiroshima.

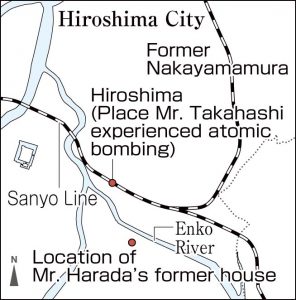

In and around 1945, Mr. Harada was living with his father Tokuji and mother Shizue in Danbara (present-day Minami Ward). On the morning of August 6, he was at Hiroshima Station with his parents to evacuate to present-day Higashihiroshima City. It was when he was waiting for the train while leaning against his father at the platform that the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. He lost consciousness. When he came to, he found himself trapped under the station roof.

Because his father covered him, he escaped from serious injury. They managed to crawl out of the rubble, but couldn’t find his mother Shizue. Flames were closing in around them. “We had to get out of here right away. Otherwise, we would die.” Mr. Harada left the station with his father, who suffered severe burns on his back, and headed east.

The roads were filled with debris and fallen people. People with shattered skulls and those without hands, feet or neck… He saw the flames approaching. He had no choice but to flee, stepping on the bodies of people even though he was not sure whether they were dead or alive. He lost his footing on exposed internal organs of the dead and felt something slimy on the soles of his feet. “I left them to die in order to save myself. This is the experience I least want to talk about.”

On that night, he stayed with an acquaintance in Nakayamamura (now part of Higashi Ward), and returned home on the following day. The ceilings and walls of the house had blown out or collapsed due to the blast of the atomic bomb. A few days later, he reunited with his mother Shizue whose whereabouts had worried him.

After the war, Mr. Harada studied hard without suffering from any serious illness, and went to university. After graduation, he worked at the city government office.

It was around the time he became director of the Peace Memorial Museum in 1993 that he began to realize that he had been exposed to the atomic bombing. People said that he was the last director who could talk about his memories of the atomic bombing, and he felt stress and strain from these words. Many of the previous museum directors were A-bomb survivors. On the other hand, he had not suffered any severe burns or scars on his body. He wondered whether he could serve in the same capacity as his predecessors as museum director.

Soon after he assumed the post, his first ordeal came. The director of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, D.C., had visited Japan and asked the Peace Memorial Museum to loan some belongings of A-bomb survivors and A-bombed related items. The NASM was planning a special exhibit, in which A-bomb related items would be exhibited along with the Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Considering this as an important opportunity to have people of the nation which used the atomic bombs learn about the atomic bombing, Mr. Harada and museum staff started to consider the possibility of lending artifacts such as the “charred lunchbox.”

This plan, however, was not realized due to fierce opposition in the United States. More people believed that the atomic bombings had brought an early end to the war and saved the lives of many US soldiers. Thinking back on those days, Mr. Harada says, “This gave me an opportunity to face the issue of how to convey the tragedy under the mushroom cloud.” In 1995, which marked the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, he was busy dealing with dignitaries and news media from around the world.

Mr. Harada also devoted himself to have the A-bomb Dome registered as a World Heritage site. Labor unions, A-bomb survivors’ groups and other organizations collected about 1.65 million signatures for support, and in 1996, the A-bomb Dome was successfully registered as a World Heritage site. He realized that collaboration between government bodies and citizens is essential for the realization of peace.

Mr. Harada is now worried that the memories of the atomic bombing will fade in the future when there will be no more A-bomb survivors. He is keenly aware that as the number of survivors dwindles, firsthand knowledge and memories are gradually disappearing in conveying the tragedy of the bombing. He strongly states, “The starting point lies in the experiences of the atomic bombing. I would like future generations to take this seriously as a matter of their own.”

(Originally published on October 31, 2022)