Thoughts from Hiroshima: Michiko Ikuta, Osaka University professor emeritus, illuminates women’s Siberia detention, speaks of story’s significance

Aug. 29, 2022

Personal notes of detainees highlight diverse circumstances and describe feelings of nostalgia

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

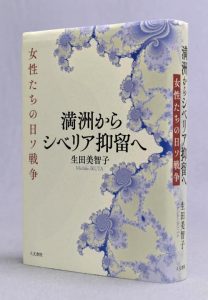

On August 23, 1945, 77 years ago, the detention of Japanese prisoners of war in Siberian labor camps was initiated by secret order from Joseph Stalin, supreme leader of the former Soviet Union at that time. Young women were included among nearly 600,000 detainees that had been sent from what was known as Manchuria (in northeastern China) to the former Soviet Union region. The actual circumstances surrounding the young women back then have been gradually uncovered by recent research. The Chugoku Shimbun reviewed the illumination and significance of the detaining of women in Siberian camps with Michiko Ikuta, professor emeritus at Osaka University, who recently compiled a book titled “Manshu kara Siberia yokuryu-e Josei tachi-no Nisso-senso” (in English, ‘From Manchuria to detention in Siberian labor camps: The war between Japan and the Soviet Union from the perspective of women’) (published by Jinbun Shoin).

According to an estimate by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, about 575,000 people were detained in Siberia. Among that total, 55,000 people are thought to have died of hunger, frigid temperatures, and disease. However, even though 77 years have passed since Japan’s defeat in World War II, the exact number of people detained in Siberian camps and how many of that total died there are as yet unclear.

Military nurses and other women are known by some to have been included among the detainees based on testimonies and personal notes. But much less is understood about the details of such women than is known about male detainees.

Around eight years ago, Ms. Ikuta, a specialist in the history of exchange between Japan and Russia, had an opportunity to meet with a former nurse in Manchuria who had been detained in Siberia. With that, she began conducting interviews with other people concerned with that history. Ms. Ikuta also researched newsletters and other materials involving reunion groups made up of former military physicians and nurses. To uncover the stories behind their testimonies and personal notes, she visited Russia and northeastern China where remnants of labor camps remain to continue her work.

In 2018, Ms. Ikuta discovered a list of female detainee names at the Russian State Military Archive, located in Moscow. For the first time in public documents, she was able to confirm the names of women she had studied.

While the personal notes and testimonies of former detainees are important in clarifying the experiences of individuals, Ms. Ikuta said, “Such information only covers what they want to or can talk about.” Therefore, it is essential to review public documents such as records of interrogations and name lists to precisely understand each of their situations, including unspoken facts. She said the name list she found helped her crosscheck the detailed actions of groups of female detainees.

The women included in the list were nurses who had worked at the No. 1 Army Hospital, located in Jiamusi near the border with the former Soviet Union. They were nurses directly employed by the former Imperial Japanese Army or dispatched from the Okayama or Hiroshima branches of the Japan Red Cross Society. Some, however, were apprentice nurses who were originally students at local girls’ schools and hurriedly trained as nurses through short periods of training. More than half were estimated to have been in their teens or early 20s.

At first, the women were forced to collect firewood or carry potatoes. However, in the winter of the first year of their detention, many male detainees were dying of frigid temperatures and hunger. The former Soviet Union mobilized detainees who had experience in medical work or public health to maintain its labor force in the camps. The nurses and apprentice nurses were sent to places such as medical clinics at different internment camps or special hospitals.

The personal accounts left by the women explicitly laid out their harsh circumstances after Japan’s defeat in the war. On a daily basis, they feared Soviet Union soldiers might commit sexual violence against them. They were sometimes forced to commit suicide if anything of that nature happened to them but, at the same time, they were notified to accept any sexual advances from the Soviet soldiers.

After being detained in the camps, the women busily cared for male detainees who had been carried into their clinics because they were malnourished or had serious injuries. In some cases, they had come down with an infectious disease and collapsed.

On the other hand, because some of their personal notes included mentions of their nostalgia for that period, an example being “I don’t have any sad memories,” the women might have accepted their detention differently from their male counterparts. The nurses were able to make certain contributions to eliminating the suffering of detainees with originality and ingenuity through their medical work. Their experiences were also likely affected by the fact that they had opportunities to interact with the physicians and nurses of the Soviet Union who shared the work of protecting peoples’ lives, even though their Soviet colleagues were on the side of the “enemy.”

Tracking of the women’s stories has led to an understanding of the varied nature of Japanese detention in labor camps in Siberia, despite the stereotyped manner in which the detentions have been described using three expressions: extreme cold, hard labor, and hunger. Ms. Ikuta said, “The information will force us to reconsider the understanding that detention in Siberia involved only men.” As Ms. Ikuta suggested, combining such story fragments will allow the formation of a three-dimensional view of Japanese detention in Siberia that had not been available to this point in time.

Despite this progress, one has to wonder why no one in society or academia had paid attention to the presence of the female detainees in Siberia.

Ms. Ikuta identified several reasons. First, the number of female detainees was overwhelmingly small. Also, in post-war Japanese society, the stories of the three keywords of suffering caught the public’s attention more than did the women’s hardships. There was also the tendency for female detainees to keep quiet about their own experiences at the time.

Ms. Ikuta assumes that the female detainees truly experienced the suffering of detention after returning to Japan, rather than during the actual detention period in the Soviet Union. Others often made the judgment that the “women had been seduced by socialism” or viewed them through a lens of prejudice that involved the assumption that Soviet soldiers violated them in some way. For those reasons, some of the women were unable to return to their families after making it back to Japan.

More than two million Japanese citizens are said to have lived in the former Manchuria as of August 1945, including those born in the Korean Peninsula, which had been under Japanese colonial rule. Ms. Ikuta points out, “We must also pay attention to the fact that women from the defeated nation who happened to be living in Manchuria had to pay the cost of Japan’s colonial occupation.” That the detainees in Siberia also included Korean nationals recruited by the former Japanese military should also not be forgotten.

The former Soviet Union cannot avoid its responsibility for violating international law and wrongfully detaining prisoners. However, the discovery of further details about the detention in Siberia of female detainees will lead to revelations about the varied aspects of detention and raise questions about Japan’s colonial rule and post-war Japanese society.

Keywords

Japanese POWs held in Siberian labor camps

In August 1945, the former Soviet Union invaded what was known as Manchuria (in northeastern China) and held in detention Japanese soldiers and civilians after Japan accepted the unconditional surrender outlined in the Potsdam Declaration. The detainees were transferred to forced-labor camps in Siberia and other places in the Soviet Union as well as Mongolia. Internees were forced to engage in such work as road and railroad construction, deforestation, agricultural labor, and factory work. Some internees were detained for more than ten years.

--------------------

Key events related to Japanese post-war detention in Siberia

August 1945: Soviet Union declares war against Japan on August 8. Emperor Showa’s imperial rescript on the termination of the war is broadcast by radio on August 15. Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union’s supreme leader, hands down a top-secret order to transfer Japanese prisoners of war to Siberia.

September 1951: San Francisco Peace Treaty is signed.

March 1953: Mr. Stalin dies.

October 1956: Japan and the Soviet Union sign the Japan-Soviet Joint Declaration, which promises to end the war between the nations, return all Japanese detainees in Siberian labor camps, and restore diplomatic relations.

December 1956: The final ship for repatriation of Japanese detainees from the Soviet Union docks in Maizuru (Kyoto). Long-term detainees return to Japan.

April 1991: Then-Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev visits Japan with name lists of detainees who died in captivity. Japan-Soviet prisoner-of-war and internment camp agreement is signed.

October 1993: Russian President Boris Yeltsin expresses apology for Japanese prisoner-of-war detention in Siberia.

June 2010: Siberia special measures law is established to pay one-time compensation to former Japanese detainees held in Siberian labor camps.

(Originally published on August 29, 2022)