Family memories 77 years after A-bombing, Part 2: Discolored ring imbued with grandfather’s love for his wife

Jul. 28, 2022

Continued mourning deaths of family members even after remarriage

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

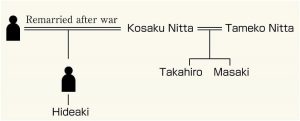

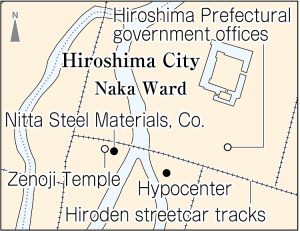

Zenoji Temple is located on one corner in an area that used to be called Sakan-cho, now part of Honkawa-cho in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. On the temple’s grounds is a memorial tower, built six years after the atomic bombing, for A-bomb victims from the area. “Here they are,” announced Hideaki Nitta, 57, a resident of the Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, while gazing at the names of three people — Tameko, Takahiro, and Masaki Nitta — inscribed on a nearby nameplate. The names are those of Kosaku Nittta’s wife and two sons. Kosaku was Hideaki’s grandfather, who died at the age of 89 in 1994.

Kosaku operated a steel materials shop in Sakan-cho. His family of four was composed of himself; his wife, Tameko, then 39; his oldest son, Takahiro, 13, a second-year student at Sotoku Junior High School; and Masaki, 11, his second son and a fifth-grader at Kodo National School, an elementary school that is now closed.

Parents looked forward to growth of sons

In a letter Tameko sent to a relative three years before the atomic bombing, she wrote, “As usual, Masaki is humorous and makes us all laugh,” serving as evidence of the tight-knit nature of the family. About Takahiro, she described her feeling as a parent watching him grow. “He is already in the fifth-grade at school, so he is busy studying every day. He is worried about the junior high school entrance exam,” she wrote, adding, “I am relieved he is now a bit more motivated to study.”

The lives of the four, however, were shattered by the atomic bombing. The family’s home was located only about 450 meters from the hypocenter, and it is assumed that Tameko and Masaki were killed in the bombing while they were at home. Starting in April of that year, 1945, Masaki had been evacuated to the present-day area of Kitahiroshima-cho with his classmates. Because he seemed to be so homesick, his parents brought him back home several days before the bombing out of pity.

Takahiro had been mobilized to engage in work involving building demolition for the creation of fire lanes in the Hatchobori area (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). Nearly all 514 of his school’s first-year and second-year students died at that worksite. The Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster (published in 1971) contains descriptions of the horrific situation. One depiction indicated that, “It was almost impossible to identify the bodies from their facial features.” Another described how, “Only a few of the children were collected by parents or family members.”

Kosaku escaped death because he was not at home at the time of the atomic bombing. He walked around looking for Takahiro, who had not returned home. On the verge of giving up, Kosaku headed to the area of Onaga-machi (now part of Hiroshima’s Higashi Ward) because he sensed his son calling out to him in that location. There, he found Takahiro’s severely burned body. Kosaku often said, “Takahiro must have died while exceedingly hot. How cruel...”

Kosaku later told his family he had thought of committing suicide after being left alone. “If I died, though, who else could have grieved for my family? While excruciatingly painful, I decided to live.” He remarried in 1952 and adopted his nephew as his son in 1959. Six years later, his grandson, Hideaki, was born.

Kept mementos throughout life

What Hideaki remembers is a small photo of the three family members that his grandfather, Kosaku, had always kept inside his driver’s license case. “When we were on family trips, my grandfather would often take out that photo and show them the scenery.” Kosaku carefully kept his family mementos throughout his lifetime, including the school uniforms of Takahiro and Masaki, and Tameko’s hood worn for protection in air raids. Kosaku died in 1994, prior to the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing. He was 89.

Hideaki now lives at the home inherited from Kosaku in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward. After sorting out the mementos, he donated the school uniforms and other materials to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located in the city’s Naka Ward. But three months ago, he discovered an envelope that read “Tameko” in the family altar. Inside was a blackened and discolored ring with a cracked gem and a hair clip. He wondered if they were accessories his grandmother was wearing at the moment of her death. The accessories made him reimagine his grandfather’s sorrow.

The owner of a civil engineering company, Hideaki takes time from his busy schedule nearly every week to visit his grandfather’s gravesite. “I do so because I think remembering them in this way is the most effective way to memorialize them,” he explained. And thus have been passed on the feelings of his grandfather, who continued to grieve the loss of his family throughout his life.

(Originally published on July 28, 2022)